Perfect Docking…Every Time

Effective communication is the key to smooth, stress-free docking.

I am an extraordinarily lucky guy. My wife Corinne is the skipper of our American Tug 41, Ocean Mistress, and she loves and excels at her job! I am completely delighted when we bring the boat into a difficult docking situation and make the perfect no-fuss, no-stress landing. I’m even more tickled when folks on the dock see Corinne come out of the pilothouse and are surprised to learn that she just docked that big boat. She has received everything from whispered compliments to standing ovations.

At a recent rendezvous, a number of women approached Corinne to inquire if she would provide lessons in docking. She had an interesting response. Along with the fact that she is not qualified as a boat-handling instructor, she felt that docking our boat was a joint effort and not a one-person task. Her comment led to some interesting discussions and reflections.

Before we continue, we offer this disclaimer! If you have a method of docking that is successful for you, stop right here. If you are interested in our techniques, please read on. Our process works for us. If you find any of our suggestions useful, adapt them so they work best for you.

By examining how we dock, we discovered that it is not just about the actions that Corinne performs, but how we do it together. Successfully docking a boat distills down to four critical factors: effective communication between skipper and mates, an understanding of how the boat behaves under a variety of conditions, preparation, and practice. You can learn all sorts of tricks for cleating down a boat or using prop-wash to improve the process. But without the four basics, it is unlikely that the tricks will be very effective.

By examining how we dock, we discovered that it is not just about the actions that Corinne performs, but how we do it together. Successfully docking a boat distills down to four critical factors: effective communication between skipper and mates, an understanding of how the boat behaves under a variety of conditions, preparation, and practice. You can learn all sorts of tricks for cleating down a boat or using prop-wash to improve the process. But without the four basics, it is unlikely that the tricks will be very effective.

Effective Communication

Let’s define what we mean by successful docking. It includes all the actions and communications from the time you decide to put the boat in a slip in the marina until the time that the lines are down, the power is plugged in and you want to hug your mate for the wonderful job!

By “effective communication,” we mean that the skipper and mate(s) have a series of communications that are completely understood by all parties to mean exactly the same thing in all circumstances. When Corinne and I botch a docking, it is always the result of a breakdown in our communications. For example, we use the term “whole boat to the dock.” This means to use the thrusters to move bow and stern to the dock. It continues until the command “stop” is used. Both of us understand these commands completely, and they result in specific and predictable actions.

Whatever else you learn from our experience, you will significantly improve your docking if all you do is communicate more effectively. The key to success is realizing that everyone who participates in the docking must agree on what each command means and the resulting actions. If there is confusion or disagreement, you will fail to dock successfully.

Whatever else you learn from our experience, you will significantly improve your docking if all you do is communicate more effectively. The key to success is realizing that everyone who participates in the docking must agree on what each command means and the resulting actions. If there is confusion or disagreement, you will fail to dock successfully.

The next important decision is to determine who’s the boss. Every vessel must have a captain. Corinne is captain on Ocean Mistress and she is ultimately responsible for the safe management of our boat. As captain, she has the right and obligation to abort a docking if she feels the conditions are unsafe.

As the mate on our boat, my role is similar to a pilot on a large ship: to communicate to the skipper the correct set of actions to take during the docking procedure. Typically, we back into the dock. I am positioned on the swim step and can see where we are relative to the dock, other vessels and any other challenges we may face. My sole job is to communicate with the captain so she can take the correct actions to put our boat safely against the dock. Then it’s my job to ensure the mooring lines are correctly tied to the dock. Once that’s done, Ocean Mistress switches from vessel to house!

Here are some simple guidelines for excellent and clear communication. All commands are simple statements. We try to use as few words as possible. Background noise is your enemy. People talking, engine noise and wind can garble the message. This is true even if you use two-way radios. Simple, short commands always work best. (See sidebar for examples.)

Giving the skipper too much information can be a problem. When we started refining our process, I tended to give Corinne a lot of situational information. I would describe all of the variables, thinking I was giving her a clear picture, and then I would continuously update her. I was trying to provide situational awareness, but instead I was creating confusion. The skipper doesn’t need to know much about the situation, only how to respond. So, she needs just the right amount of information – and make it geographically relevant.

Giving the skipper too much information can be a problem. When we started refining our process, I tended to give Corinne a lot of situational information. I would describe all of the variables, thinking I was giving her a clear picture, and then I would continuously update her. I was trying to provide situational awareness, but instead I was creating confusion. The skipper doesn’t need to know much about the situation, only how to respond. So, she needs just the right amount of information – and make it geographically relevant.

Essentially, a boat moves in two dimensions. We use the dock we are trying to land on as our fixed reference. While docking, all commands are given relative to the dock. Each command is given to guide the boat either toward or away from the dock. No other information is provided and no other discussion takes place.

Understanding Vessel Behaviour

Ocean Mistress is 46’ long, 16’ wide and has a big, tall bow. She is light and sensitive to wind on the beam or forward quarters when the breeze is 10 knots or greater. At slow speeds she will not turn very quickly. At docking speeds, she will not turn into the wind without using the bow thruster and sometimes even the stern thruster. So our preference is to back into the wind. The bow likes to follow the stern so it is very much like steering a wheelbarrow.

Ocean Mistress is also very sensitive to current. In the Pacific Northwest, where we cruise, current is ubiquitous. I have seen us go surprisingly fast and far sideways. This can present a challenge if you are not prepared for it. On a trip to the Broughton Islands, we spent a night at Blind Channel Resort. The docks there are subject to strong current and dock hands will communicate direction and speed of the current. Armed with this information and a relatively empty marina, we decided to aim Ocean Mistress for the middle of the slip, expecting the current to move us toward the dock. The current definitely moved us toward a dock, but not the one we expected. With new situational awareness, we pulled out and made a more successful landing. When we were safely tied up, we realized that the current in the channel was definitely going in the direction reported. But a back eddy had started along the shore. I failed to notice that the kelp strands were lying in the opposite direction to the main current.

We have no problem aborting a docking attempt and trying again. Despite your very best efforts, practice and experience, there will be situations when docking may not go as planned. When events get the better of you, the best decision you can make is to stop the boat, get yourself back into the fairway or even leave the harbour until you collect yourselves.

I do not like to jump from the boat to the dock. Actually, let me be clear: I do not jump from the boat to the dock. Early one boating season, we messed up and ended up 10’ from the dock. Several volunteers suggested that we throw our lines to them and they would pull us in. Instead, Corinne aborted the docking and pulled back into the fairway. She got us out of trouble and then backed us in perfectly. I stepped off in a relaxed manner to tie us up. We needed the practice but more importantly, throwing lines is irresponsible. Ocean Mistress is a big boat. If we were caught by current or wind, we could easily pull a volunteer into the water.

Preparation

Docking starts well before you enter harbour. In fact, it should start with acquiring proper charts and guidebooks with marina descriptions before you leave the dock. Once you have them, use them. Typically, we review the guides well before we reach our destination and we have them open at the helm for quick reference when we contact the harbourmaster for a slip assignment.

Before we enter the harbour, we put out our fenders and prepare all our lines. We always prepare Ocean Mistress the same way. We have two fenders on the docking side, bow and stern lines, and two midship lines. The bow and midship lines are set up so they can be accessed from the dock at the middle of the boat. The stern line is tied on the rear cleat and accessed from the swim step.

Next we have a little conference at the helm and discuss any unusual conditions or address any issues that Corinne or I might have recognized. We use this opportunity to test two-way radios when we use them. Corinne will take a minute to review the harbour directions and dock layout in a guidebook.

Our last check is to confirm with one another that we feel it is safe to enter the harbour. If the conditions are marginal, with strong wind or current, lots of boat traffic or some other condition that might present a hazard, it is much easier to abort the docking before we are in tight quarters. Sometimes an alternate location nearby may be the safer choice.

Practice

You won’t improve unless you practise. When Corinne and I purchased Ocean Mistress, our first few trips were designed to practise the skills we would need to handle her. We found a nice, big, open dock and practised side-tying with both port and starboard approaches. Practice helps you perfect your technique. When we practice, we perform the skill or task exactly as we would in a “real” situation. It is difficult to attempt or learn a new skill when you are in a stressful situation. Figuring out what will happen in advance, under calm conditions, builds confidence in the vessel and crew.

Remember that docking successfully comes down to effective communication between skipper and crew, a sound knowledge of boat behaviour under a variety of conditions, preparation, and practice. Communicating effectively during docking will increase your confidence and improve the trust between skipper and crew. With a little time and practice you will find that you are docking like a pro.

Effective Communication

Here is an example of the commands we might use to back into a typical marina slip that is 46’ long and can accommodate two boats between the finger docks.

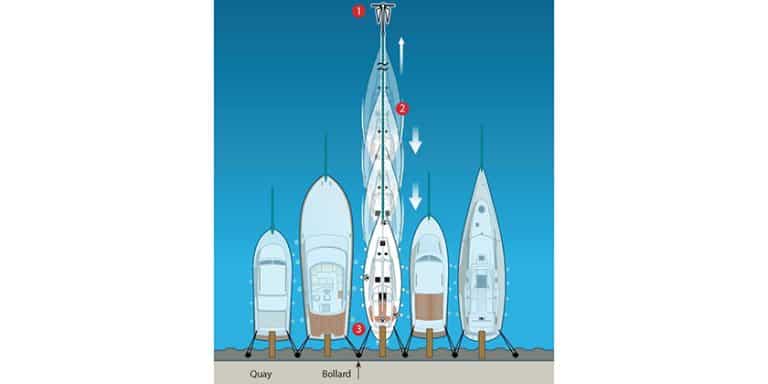

Corinne maneuvers the boat along the fairway and prepares to stop and back Ocean Mistress into a slip. I am positioned on the swim step. I watch for traffic coming up behind us and get ready to tell Corinne when to begin her turn. The following are the commands I will provide from the swim step. All commands will be given in a loud voice (unless I am wearing radio). Corinne takes all actions at the helm.

‘Stop the boat’ (stop forward momentum on the boat)

‘Stern to the dock’ (use rear thruster to push boat to the dock)

‘Reverse’ (shift into reverse gear)

‘Bow away from the dock’ or ‘Bow away’ (use forward thruster to push the bow away from the dock)

‘Stop reverse’ (take boat out of gear)

‘(Whole) boat to the dock’ (use bow and stern thrusters to move us toward the dock)

‘Enough’ (stop using thrusters)

‘Reverse’ (shift into reverse gear)

‘15 feet’ (The distance from the stern of the boat to the cross pier of the dock. This is the only situational information provided. As we back down the dock, Corinne can judge how fast we are going and adjust our speed. This is about the only action she will take independent from my commands.)

‘(Whole) boat to the dock’ (we need to get a little closer – I don’t jump!)

‘Stop’ or ‘Forward’ (I use either command depending on situation)

‘5 feet’ (More situational awareness)

‘Off the dock’ (This means I screwed up and need Corinne to use a short burst of the thruster away from the dock. I don’t like hitting the dock!)

‘Stop the boat’ (I step off the boat, go forward and start tying the lines. I typically start with the forward spring but always use the line opposite to any current acting on the boat.)

Notice that my first act is to walk up to the beam of the boat so Corinne can see me and know that I have not fallen in the water. Corinne has not yet left the helm. She continues to help position the boat so I don’t have to tug on lines. That part might sound something like this:

‘Bow to the dock’ (Need the bow closer to the dock – Corinne provides a short burst)

‘Bow to the dock’ (A little more thruster)

‘Stern to the dock’ (Need stern closer to the dock)

At this point, Corinne usually checks to see if we are secure and if I need help with the shore power cable.

PHOTO CAPTIONS

Photo 1 – he skipper checks on the mate. The spring lines are down and the boat is secure. Prince, our dog, inspects our work!

Photo 2 – Shawn checks proximity to the dock and communicates direction and distance to Corinne at the helm.

Photo 3 – Shawn steps from swim grid to dock to secure the lines.

Photo 4 – Shawn prepares to secure the spring line.

Story by Shawn and Corinne Severn

Photos by Keith Short