Cored Deck Repair

By Andrew McDonald

The rotten core of a companionway hatch. The backing has been cut out to expose the core

It’s race night and the breeze is strong. Sails are full, the rigging is taught and the crew are working hard. Footfalls hit the deck and bodies move across the cabintop. The boat is tacked and sails are changed. Sheets are tightened and maximum downwind speed is reached.

While all of this is happening, the boat is flexing under tremendous pressures. The stays and chainplates pull at the edges of the hull, squeezing it’s shell. As sheets are tightened, deck hardware is strained. The pounding of the boat through choppy water acts like a series of jabs in a prizefight. Walking, stepping, and jumping cause the curved cabin top and decks to alter their shape slightly.

All of this takes place in a rapidly changing marine environment. The effects of flexing and movement are exacerbated by the pounding movement of water, and the elements of sun and rain attacking from above. To make matters worse, we allow the shells to freeze onland for 5 months of the year, with drastic changes in moisture content and temperature during this period.

Given all of this, it’s no surprise that when the race is done and sails are being packed away you step back and notice new spider cracks in the gelcoat, or the feeling of a ‘soft’ or ‘spongy’ spot in the deck as you tread across it. Before the ‘how’ and ‘why’ and ‘cost’ of this starts to sinks in, lets examine what a ‘spongy’ deck really means, and how to address is.

The shell of a fiberglass boat is made of multiple layers of material, each with different properties – essentially a sandwich of a core material (often a wood or balsa), surrounded by a alternating layers of fiberglass materials, topped off with a layer of gelcoat. At some point during the 1960’s, wooden boat manufacturing was replaced by fiberglass techniques and processes. As this evolution took place, much thought was given to high production output, low production costs, ease of labour, and the weight and durability of the finished products. In the decades leading into the 1990’s, the boats produced were made with decks made of balsa core material – a low-cost wood product, very lightweight, and ideally suited to strengthening large surfaces and curved shapes. Hundreds, if not thousands, of the boats built during this period are still being enjoyed today.

The exposed rotten plywood-core deck

The exposed rotten plywood-core deck

In the 1990’s, production techniques began to evolve further. Fibreglassing techniques, and the new scantlings derived from thinner, more lightweight hull forms propelled the use of epoxies, carbon fibre and Kevlar. In modern production boats, core materials and ‘spongy’ decks aren’t as much of a concern. But the hundreds of thousands of productions vessels produced by the likes of C&C, Catalina, CS Yachts, O’Day and Grampian, in the period between 1970 and 1995 are likely to develop deck core issues. This is truly what we’re discussing – the damage, water intrustion and subsequent rotting of the core material of the vessel’s deck.

A key component of a quality marine survey is a testament to this fact. A surveyor will spend some time reviewing moisture meter readings and using a tool to tap at various points on the hull surface (inside and out), the decks and superstructure. The moisture meter will indicate if the core material is saturated with water, and the tapping will indicate (through percussive testing) if delamination – the separation of the layers of the fiberglass and core – has occurred. These tests are the best way to determine if there’s cause to panic when the deck sags beneath your weight.

With the stress, strain, environment and use of materials, it’s almost inevitable that the core material becomes wet and rotten over time. The deck flexes and strains, and the layers the comprise the deck each flex and move at their own rate: The core is light and highly flexible, the layers of fiberglass surrounding the core strengthen it, but still allow movement. The gelcoat is thin, hard and the least flexible of all. Through the layers, deck hardware is attached using machine screws, backing plates with a dab of caulking. Over time, the caulking shrinks and rots, water permeates and soaks into the core. The water has nowhere to escape, so it leaches and spreads within the core, soaking a large area. Time marches on as this water intrusion occurs; in the winter, the water will freeze and expand, allowing more water to permeate the following spring. As the core soaks, it delaminates from the surrounding fiberglass layers, losing its strength and changing the way the pressures are supported when strained. The gelcoat surface layer may begin to crack in areas of strain. The deck ‘gives’ when it is stepped on and feels like a wet sponge underfoot.

A completed section of replaced core, fibreglassed over and faired smooth

A completed section of replaced core, fibreglassed over and faired smooth

There’s no cookie-cutter approach to a repair – the method used will depend on a number of factors, including: the extent of damage, the hardware adjacent to the deck damage, whether the deck has smooth or non-skid surfaces, underside deck access, and the ability to match the repair area to the surrounding surfaces. That said, a quality repair will follow a general process:

1) Identify the extent of the repair

It’s tempting to think that the use of a moisture meter is a simple, non-invasive way to test to see if the core is wet or rotten. The truth is, the use of a moisture meter on fiberglass is a bit of an art, with varying degrees of success in interpreting the results. There are many factors that skew results: The varying thicknesses of the fiberglass and resin layers, the difference in materials used, and the reliability of the device. Two more reliable methods can be used along with a moisture meter to determine the damage: the use of percussive testing (knocking on the hull surface to see where the fiberglass layers have separated from the core material), and drilling small pilot holes to see and feel moisture in core samples.

2) Determine the best approach

Most of us appreciate the aesthetics of a seamless repair that isn’t a glaring eyesore once completed. Sometimes its possible to work from the underside of the deck, or perhaps to work along the seams of non-skid deck areas. The entire repair should be evaluated from the perspective of how things might look once completed.

3) Cut into the fiberglass and remove the rotten core

The outer fiberglass layer should be cut away to expose the damaged core. It will need to be cut back beyond the damage to clean and dry core, with enough area exposed to chamfer and lay up new fiberglass in later steps

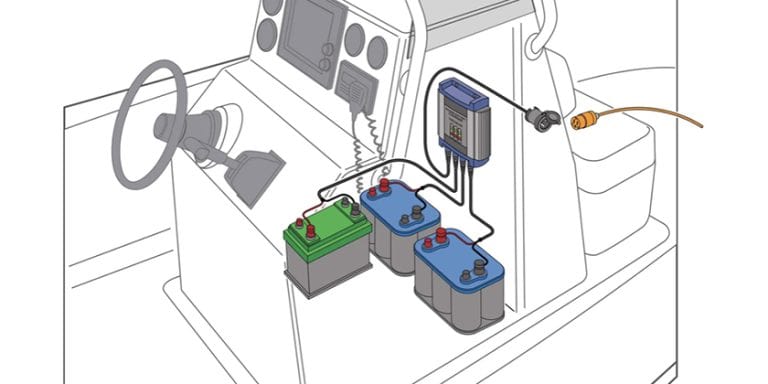

4) Remove any adjacent hardware and sealant

These will only get in the way as the repair unfolds, and the hardware should be re-installed and re-bedded once the repair is completed.

5) Replace the core

The inner surface of the fiberglass should be prepped by sanding/scuffing, cleaning with acetone and laying new resin to allow the replacement core to adhere. Be sure to match the core type and thickness with the original.

6) Lay-up new fiberglass

The edges of the repair area should be chamfered appropriately. Once the core is layed in place, wet it out thoroughly and lay-up new layers of fiberglass. Once cured, use a filling/fairing compound to match the curvature and shape of the surrounding deck.

7) Roll or spray new gelcoat

Once the deck repair is faired and smooth, apply a fresh coat of gelcoat 0.5-1mm thick. Once cured, wet-sand and polish. If non-skid areas need to be repaired, use an appropriate mould or granular additive to match the surrounding finish.

8) Replace hardware and seal appropriately.

Any hardware that was removed should be replaced and bedded appropriately

Any hardware that was removed should be replaced and bedded appropriately

Using a mould to match a repair in a non-skid pattern

As you can see – it’s simple to write a few step-by-step procedures. It’s another thing to effect a quality repair. With a confident skill-level in the use of fiberglass products, this can be a do-it-yourself project. That said, for someone less confident, hiring a repair tech may be a logical part of the planning process.