No More Captain Crash! Embarrassment-Free Docking

By Brenda and Doug Dawson

While docking a sailboat has remained largely unchanged over the centuries, power boat designs have changed dramatically, even over just the last four decades. Now, power boats come in dozens of styles, shapes and sizes from runabouts to motor yachts, trawlers, houseboats, pontoons, ski boats and many more. They also come with many different drive systems; single, twin, triple and in some cases, quad motor installations.

Each of these engine and drive systems perform and handle differently and as a result, different handling and docking techniques are required to accommodate these various designs and the challenges they create. In the 1940s and 1950s, the old fashioned method of handling and docking suited all power boats because they were basically all the same—low freeboard, full-length keels, single inboards, rudders, props, big wide side decks and flat foredecks. Not anymore!

Boaters who don’t understand that each requires different handling and docking techniques, are those needlessly suffering through sometimes disastrous docking experiences and who risk alienating their families from boating forever.

In this article we will illustrate just two of the many significant challenges in power boat handling and docking; docking mid-cabin express cruisers and whether or not to use the steering with a twin engine boat. We will share a few tips and solutions you can use this summer.

In this article we will illustrate just two of the many significant challenges in power boat handling and docking; docking mid-cabin express cruisers and whether or not to use the steering with a twin engine boat. We will share a few tips and solutions you can use this summer.

Mid-Cabin Express Cruisers

Since the mid 1980’s, mid-cabin express cruisers have become the most popular style for families, giving them two distinctive sleeping areas—mid-cabin and v-berth. Most boaters don’t realize though that the layout changes have made these more difficult to dock than many earlier power boat designs.

Manufacturers re-designed smaller cruisers to include more sleeping accommodation with the introduction of the mid-cabin. A mid-cabin cruiser is an express cruiser with a cabin under the forward cockpit sole. Having extra sleeping amidships is a great feature for family or guests, but what was compromised to gain this space?

Narrow Side Decks or No Side Decks

Narrow Side Decks or No Side Decks

• To create more room on the inside, some space had to be taken from the outside, leaving the side decks narrow to non-existent. So, how do First Mates move safely from the cockpit to the bow to tie the bow line when docking? The answer is, they can’t. Even if they could, the foredeck is often sloped, slippery when wet and the rails are too low for safety.

• Also, the cockpit sole which is built up over the motor and mid-cabin, elevates the crew above the typical low floating dock. This configuration makes it difficult to attach a dock line from the cockpit to the dock cleat.

• Complicating that, the often shallow cockpit gives crew members a feeling of insecurity, when leaning out to reach a dock cleat because of the shallow cockpit depth (waist height freeboard compared to knee height).

• First Mates should stay off the bow when docking. It is not a safe place and you can’t reach a floating dock cleat from there anyway—even with a walk-thru windshield.

Tip

To outsmart the “narrow side deck” or “no side deck” challenge of today’s mid-cabin boats, the First Mate should use the swim platform or aft corner of the cockpit when docking. For the First Mate, either is closer to the cleat on low floating docks and easier to reach with a dock line.

Solution

Solution

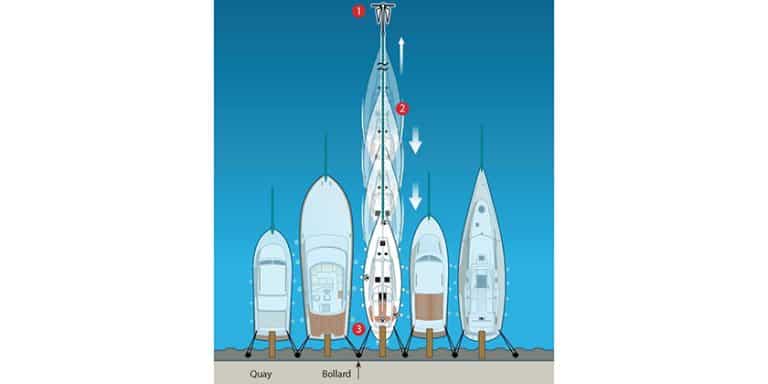

•The First Mate starts by securing the eye splice through the stern cleat. Hold the balance of the line in two hands to form a large loop.

•Once the First Mate is ready, the Captain can bring the stern in close to the dock cleat—regardless of where the bow is.

•When close enough, the First Mate tosses the centre of the line beyond the cleat, pulls in the loose end, tightens to eliminate all the slack, then ties on the boat’s stern cleat with a figure eight cleat hitch—short, fast and tight.

•When the line is secure and fingers are clear of the knot, the First Mate immediately signals the Captain with a thumbs-up.

•Now the Captain can nudge the shift into forward idle. The boat will swing in tight to the dock and hold there while either of them steps off to tie the docking lines.

•Pull the shift into neutral. Turn off the motor(s). Smile and take a bow to your amazed (previous doubting) admirers.

•This docking procedure works when kneeling in the aft corner of the cockpit or standing on the platform—just remember to hold on to the stern rail for safety. This procedure should be practiced on a spacious parallel dock. Once mastered, proceed to your tight slip.

To “Wheel” or “Not to Wheel” When Docking a Twin Engine Power Boat

There is great discussion and confusion around the question, “Should I use the wheel when docking my twin engine power boat?”

The right answer depends on several factors, but most importantly, whether you are docking twin inboards or twin sterndrives / twin outboards.

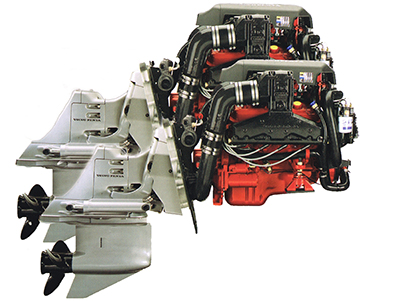

On twin inboards, the propellers and rudders are under the boat; whereas, on twin sterndrives/outboards, the propellers and outdrives are out behind the boat. Therefore the thrust and its effect on the boat cannot be the same.

On twin inboards, the propellers and rudders are under the boat; whereas, on twin sterndrives/outboards, the propellers and outdrives are out behind the boat. Therefore the thrust and its effect on the boat cannot be the same.

The biggest problem using the wheel on any twin engine boat is not returning the wheel back to top dead centre; i.e. straight ahead, thus not slightly off to port or starboard. For the maneuver that follows, the boat won’t go straight ahead or straight back or pivot on the spot, when the wheel is not dead centre.

There are tricks you can use to mark your wheel like black electrical tape or a notch, but in the heat of the moment, with so many things going on, even with the wheel marked, seasoned captains can get it wrong. The most important thing to consider is whether you are docking a twin inboard, or a twin sterndrive/outboard because handling for the inboards is totally different when docking.

Let’s look at Twin Inboards first.

The thrust on a twin inboard is from two fixed propellers under the boat with two rudders behind the propellers for steering. The boat’s bottom traps or captures the propellers’ energy improving the leverage to pivot the boat.

Using the wheel and one shift won’t work for you. You’ll end up just going back and forth on the same path—i.e. forward to port, then backwards to port. As a result, you never go to starboard. When you add throttles, you overload the brain, because both throttles must be re-synchronized for the next command; otherwise, you are rowing harder on one side than the other.

You need to be able to control your boat’s movements to make it do exactly what you want it to do.

Tip

Tip

Don’t use the wheel when docking a twin inboard, use only the shifts. Set the wheel dead ahead, then forget it exists. Synchronize the two motors at say 800 rpm. Then, forget the throttles exist. These two distractions are out of your overloaded mind all the way from the fairway until you are tied.

Solution

•When handling or docking a twin inboard, one of the most important lessons to master is turning/pivoting your boat on the spot so that you can maneuver in the confines of the harbour and your slip.

•To dock a twin inboard, use only the two shifts—one in each hand. Mentally duct tape one hand to each shift until docked, then you won’t grab a throttle by mistake. Now use your body language to control the boat.

•To turn to port (left), turn your body to port. Your right hand goes forward, pushing the starboard shift into forward and your left hand goes back, pulling the port shift into reverse. Your boat turns to port.

•Similarly, to execute a turn to starboard (right), turn your body to starboard. Your left hand pushes the port shift forward and your right hand pulls the starboard shift in reverse. The boat turns to starboard.

•To stop forward motion, leaning back, pulls both shifts into reverse. Also, to advance the boat ahead, lean ahead—both shifts get pushed into forward.

•Practice using body language in open water to watch and experience your boat following your body language. Master making your twin inboard do exactly what you want it to do before approaching the dock/slip.

Twin Sterndrives or Twin Outboards

Twin Sterndrives or Twin Outboards

If you use the wheel on a twin sterndrive/outboard, handling both motors like a single, you will be able to dock, but your turning radius will be much larger than it should be and you will be advancing too fast. This isn’t the ideal way to dock and could result in a much bigger scrape.

If you use the wheel and only one motor, as if it were a single, it will turn well one direction, but not the other. You could dock this way, but it isn’t ideal because the active propeller is off centre.

If you use the wheel, with one motor in forward and one in reverse, the reverse thrust is cancelled out because the one in reverse is aimed the same direction as the one in forward. As a result, the boat won’t turn and the boat certainly won’t pivot the way a twin inboard will.

Centering the wheel on a twin sterndrive/twin outboard and using the two shifts like you would on a twin inboard, won’t work well for the following reasons:

• The propeller thrust on a twin sterndrive/twin outboard is lost out behind the transom of the boat because this thrust is not contained under the hull bottom.

• The leverage is poor because the props are usually closer together than on twin inboards, which also decreases leverage resulting in a weak pivot.

So, when you add all these factors together and try docking a twin sterndrive/outboard like a twin inboard, you don’t stand a chance to control the boat.

Tip

Don’t do any of the above. Don’t do what doesn’t work. Practice only makes perfect when you practice the correct procedure; otherwise, you get good at doing it wrong!

Another tip is to use the palm of your left hand to turn the wheel. Keep your right hand across both shift levers and don’t remove your right hand to steer the wheel hand-over-hand. This way, your right hand will remember which shift it is on and which gear it’s in. Too often, when boaters turn the wheel hand-over-hand, the right hand returning to the shifts forgets where it was and grabs the wrong one. In other words, mentally duct tape your left hand to the wheel and bridge the shifts with your right.

Solution

Solution

•To execute a tight turn to port (left), turn the wheel hard over to port, then push the starboard (right) motor into forward for 10 seconds. Leave the port in neutral. The boat will turn sharply to port.

•Next, pull the starboard back into neutral momentarily. The boat continues to pivot almost on the spot to port. Wait patiently until it slows, then push the starboard in forward again for 10 seconds. The bow will continue turning to port.

•If you run out of space to go into forward again, turn the wheel all the way hard over to starboard. Now pull the port shift into reverse for 10 seconds. The transom goes to starboard but more importantly, the bow continues to turn to port. Repeat until you have turned 360 degrees. This way, the process becomes automatic in your brain.

•Once you have mastered this turn to port, repeat going to starboard. Practice these maneuvers in open water before attempting close quarters maneuvering in the confines of the harbour.

Conclusion

The subject of handling and docking power boats is big enough and varied enough to fill many books. But, it is important to at least understand why different techniques are required. Sailors and power boaters alike benefit from knowing what each is faced with and how to help each other—not sit and laugh. To help understand what all the changes are to power boats over the decades and what challenges are created, download the free 24-page report “Why Power Boat Docking is Difficult”.

Doug Dawson, a 5th generation boating industry professional, has been a boat tester for Canadian Yachting magazine as well as other boating magazines since the 1980’s, and a person who has driven hundreds of different engine and boat configurations. Together with his wife Brenda, the Dawsons have authored 17 e-Books (from 125 to 230 pages each) on handling and docking boats (both power and sail), simplifying docking for recreational family boating. Their FLIPP Line™ procedure takes the fear out of docking and is safer for all on board. Go to www.PowerBoatDocking.com or www.SailboatDocking.com for more information.

Doug Dawson, a 5th generation boating industry professional, has been a boat tester for Canadian Yachting magazine as well as other boating magazines since the 1980’s, and a person who has driven hundreds of different engine and boat configurations. Together with his wife Brenda, the Dawsons have authored 17 e-Books (from 125 to 230 pages each) on handling and docking boats (both power and sail), simplifying docking for recreational family boating. Their FLIPP Line™ procedure takes the fear out of docking and is safer for all on board. Go to www.PowerBoatDocking.com or www.SailboatDocking.com for more information.

FLIPP Line™

Dawson’s FLIPP Line™ is a temporary docking aid that simplifies docking by allowing you to change your boat’s pivot point to effortlessly secure your boat to the dock/pier without the need for yelling, swearing, jumping, boat hooks, bionics, dock helpers, guesswork or embarrassment. Once secure, your boat should be tied appropriately for the situation. The FLIPP Line™ procedure is explained in detail over several pages in each Introductory Docking e-Lesson.