Boat nerd: Boat DC Electrics – part 1

Jan 13, 2022

Use insulated tools, or wrap yours with electrical tape

This series deals with basic DC boat wiring concepts. From various articles and posts I see, and talking with boating friends, there seems to be mystery for many when it comes to boat electrics. I don’t intend this to be a deep dive but hopefully enough to take away some of the mystery.

If you are well versed in this topic, let me know if there are tips and tricks you’ve learned and might make someone else’s wiring job easier.

Safety First

This article is meant as an aid in the understanding of electrical concepts and function as a general guide. It should NOT be used to address specific boat issue – be fully informed or seek the help of an experienced professional before attempting any electrical work on any boat.

Electricity can be dangerous. It only takes a small current (100-200mA) running across the heart (for example from one arm to the other) to disrupt the normal rhythm of the heart or stop it entirely.

Voltages under 50V are generally considered fairly safe because of the high resistance of human skin. However even at 12V, if you are sweaty, you can feel a tingle when touching live terminals. Ask me how I know!

Remember:

• AC and DC voltages can be potentially harmful

• Use insulated tools, or wrap yours with electrical tape, when working anywhere near live terminals. Isolate/disconnect power sources whenever possible before working on your project. Remove or tape rings. Again ask me how I know.

• Batteries, especially lithium, can provide tremendous fault currents. You do not want to short the battery terminals. You can melt the area of the tool that contacts the battery terminals. Wear safety glasses.

• When working with Lead Acid batteries, charging can create hazardous/explosive gasses such as Hydrogen

• Corroded connections can overheat and cause a fire at high currents

Always consult local safety guidelines. For marine applications in North America those will be produced by the American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC).

If unsure of your capabilities, hire a certified marine electrician, especially when dealing with 110VAC.

According to insurance statistics from BoatUS, 55% of fires on boats are of an electrical origin, with half of those coming from short circuits in DC circuits. This is one area it pays to do any work correctly.

Direct Current vs Alternating Current (DC. Vs AC)

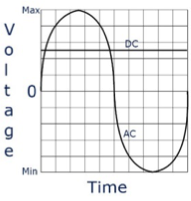

Direct current always flows in one direction, typically at a constant potential or voltage. This is normally what you will find on a boat.

Alternating current on the other hand is in the form of a sinusoid, rising from 0 to an upper maximum potential, then dropping back through 0 and continuing down to the same lower minimum potential, before rising back to 0 again and repeating. This is one cycle. In the North American power grid we get 60 cycles per second or 60Hertz. In Europe they use a 50Hz standard. While you can easily change the voltage, changing frequency is much more difficult if you’re looking at using European appliances in North America or visa versa.

AC voltage is normally measured as Root Mean Square (RMS). The RMS voltages can be defined as the equivalent DC voltage that would dissipate the same power in a resistor. In North American homes we typically use 120VAC RMS, which works out to about 170V peak. (Peak Voltage x .707 (square root of 2) equals RMS voltage)

See figure 1.

Fun fact – In the advent of electrification in the early 1900s, we had the current war whereby Edison’s DC system was competing with Tesla’s/Westinghouse’s AC system. Edison lost.

Volts, Amps, Resistance, Power, Energy

What are these entities, where will I run across them, and why should I care?

Volts (written as “V” or occasionally” or “E”) is a potential difference that causes a current of electrons to flow and can be thought of as the height of water in a rain barrel. The higher the water level in the barrel, the higher the pressure exerted and the potential.

Probably the most common voltage you’ll run into on a boat is 12V. However 24V or 48V is becoming more common for reasons we’ll discuss later. Some boats have oddball 32V or 36V systems.

Amps (written as “I”) is the current flowing in a wire or system. Going back to our rain barrel analogue, if you have a small hole in the bottom of the barrel, you get a small stream of water (a small current). If you make the hole bigger you get a larger stream of water (a higher current).

On a boat many items draw small currents. For example LED cabin lights typically draw under 1A. A refrigerator may draw 6A or so when it is running. Then at the other end of the current spectrum you have items such as a windlass, electric winch, bow thruster or inverter that can draw upwards of 100A.

Resistance (measured in ohms and written “R” or the Greek letter omega Ω) is the impediment to the passage of electricity. Some items like metals (especially copper or aluminum) conduct or pass electricity fairly well and are said to have a low resistance. Other materials such as nylon and plastics act as insulators and have a very high resistance.

Resistance is equal to rho x length/area where rho is the specific resistance of the material measured in Ohms-meter. At the top of the list for least resistance are the metals silver, copper, gold and aluminum. This is why most wire is made of copper or aluminum. Near the bottom of the list is steel. For this reason where you are requiring a bolt to actually carry current, do not use stainless steel.

What the formula tells us is that a fatter wire with more cross sectional area will have less resistance than a thinner wire of the same length. Similarly a longer wire of the same diameter will have more resistance (and hence voltage drop) than a shorter length of this wire. This is why for long runs of wire you typically must use larger sized wire.

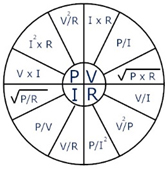

These three quantities are related by a simple mathematical expression called Ohm’s law after George Ohm. R=E/I Dividing the voltage across an element by the current through it gives you the resistance of that component. See Figure 2.

When you have two of the quantities you can use Ohm’s law to find the third. Just cover the missing quantity in Figure 2 and use the two values you have left as indicated. For example if you have a wire with .001 ohms of resistance and you run 100A through it, what will be the voltage drop across the wire? Covering E in the figure, shows you multiply the current (I) by the resistance (R). In this case you will have .001 ohms x 100A or a 1V drop across the cable. This is the basis of a later section when we look at wire sizing.

Power is measured in Watts (written as “W”) and is the product of Volts times Amps (V x I). It is the ability to do work. There is no concept of time involved in the definition of Power.

Using this formula, if our cabin light draws 0.5A at 12V then it is consuming 6W. If our windlass draws 100A at 12V then it is consuming 1200W when it is running.

Watts are independent of voltage. For example let’s take a fan that draws 24W. If we buy a 12V version of this fan, it will draw 2A. Should we buy a 24V version of this fan it will draw 1A so the Watts remain the same.

I’ll briefly touch more on inverters later (for powering household appliances/electronics on a boat by transforming 12V to 120V) but for another example of Watts staying the same, let’s think about a 1200W kettle. Plugging the kettle into the wall in our kitchen it will draw 10A at 120V. If we then take it to out boat where we have an inverter it will draw 10A at the inverter 120V output, however it will draw 100A at the inverter 12V input (assuming an ideal case of no power losses in the inverter).

Using Ohms law (R=E/I) and the formula for Power (V x I) we can create figure 3 where knowing any two of the quantities you can calculate the third.

Fun fact, 746 Watts is equivalent to 1 Horsepower. If your engine driven alternator is putting out 80A at 14 V it is supplying 1,120W of power or 1.5HP. This power is deducted from the engine rating and what is left is then available to drive your prop, but that normally isn’t an issue.

Energy is power consumed over time. It is measured in Amp-Hours (AH) or more accurately Watt-hours (WH) (Fun Fact, or Kilo Watt Hours (KWH) if you’re reading your house electricity bill!). Thus energy is amps x time or more accurately Watts x time (or written another way Volts x Amps x time).

As an example if you listen to your boat stereo that draws 1A @ 12V for 2 hours you have consumed 2 AH (1A x 2hours) or 24 WH (12V x 1A x 2 hours).

Standards

The American Boat & Yacht Council is an organization that sets voluntary standards for all aspects of boat manufacture and repair. These standards are reviewed and updated periodically to keep them current. The current standards are available from ABYC for a cost. Older versions may be available for download from the Internet. The standard that covers much of what is discussed in this article is E-11.

Next time – Jan 27: Part 2 – Wiring your Boat

CYOB’s Boat Nerd, Mike Wheatstone, has enjoyed sailing since he was in his mid teens. A Queen’s electrical engineer by training, he spent his career working for Ontario Hydro and Hydro One. There he worked in engineering supporting the power system control centres.

CYOB’s Boat Nerd, Mike Wheatstone, has enjoyed sailing since he was in his mid teens. A Queen’s electrical engineer by training, he spent his career working for Ontario Hydro and Hydro One. There he worked in engineering supporting the power system control centres.

His first boat in 1980 was a Shark. With a growing family’s 2-foot-itis, there were upgrades to a Grampian 26, CS34 and currently a Hunter36. Now retired, Mike and his family spend summers on the Hunter (Dragonfyre) and winters in the Caribbean on their Leopard 43 cat (Peregrine).