Safety at Sea: Creating a Culture of Safety

May 4, 2020

By Rob MacLeod, The Informed Boater

By Rob MacLeod, The Informed Boater

Figure 1 Life Raft Sequence

In my 45 years of teaching sailing and boating there has never been a subject more aligned with my love of boating and cruising than this one. Each person I talked with about Safety at Sea spoke with commitment and passion about the importance of creating a Safety Ethos (Culture of Safety) aboard each boat, fleet, club and association.

Let me start with a personal story from the start of my sailing journey. I was 25 when I learned to sail. I was hired by a new sailing school at the ‘then’ Hamilton Harbour Commissioners (now the Hamilton Port Authority) under the leadership of Ian Robertson. Why hire a non-sailor for a sailing school?

Let me start with a personal story from the start of my sailing journey. I was 25 when I learned to sail. I was hired by a new sailing school at the ‘then’ Hamilton Harbour Commissioners (now the Hamilton Port Authority) under the leadership of Ian Robertson. Why hire a non-sailor for a sailing school?

My role, after a number of years with the Boy Scouts, was to lead the shore-based activities. In addition to my duties as activity leader, I was given the opportunity to learn to sail. It was a few years later before I truly realized the incredible gift I was given. Three of Canada’s top sailing instructors taught and coached me – Ian Robertson, Karen McCrae and Mike Hines. By the end of the summer, I was an assistant instructor in one of the adult Learn to Sail programs and I learned to be comfortable in a PFD at all times, in all weather.

Fast forward 30 or so years. When I first took guests out on my CS36, I would do a safety briefing – moving around the boat and safety equipment, including PFDs. I would show my guests where the PFDs are stowed and ask them to put them on if they wanted to. Few did.

A few years later, I changed my approach. Before my guests arrive, I lay out the PFDs according to the size of my guests. If I am short a PFD, my dock neighbours are happy to loan appropriate PFDs to complement my inventory. As my guests board, I ask them to select a PFD, put it on and then I help them adjust the straps until the vest fits properly. Then I tell them, “If you are in the cockpit or below deck, you are welcome to take your PFD off. Stow it somewhere where you can find it when you need it. If you go out on deck – please put it back on.” The majority of my guests leave their PFD on, even sitting in the cockpit and those that take them off, put them back on when they leave the cockpit. One small change on my part means my guests were more comfortable wearing their PFDs while underway and makes for a safer sail.

Safety at Sea – The Clinic

In preparing for this article, I called a friend and asked if I could interview her for this article. Diane Reid, a very active offshore sailor and instructor, immediately said yes. In fact, Diane and fellow Sail Canada instructor – Jamie Gordon – were conducting an Offshore Personal Survival clinic the following weekend and I was invited to join them and 12 participants at the Ontario Sailing office. I had now gone full circle – back to where I had started my instructor career in Hamilton, Ontario.

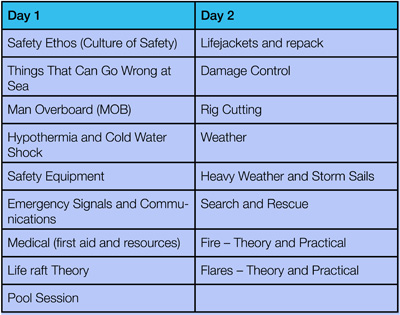

Sail Canada’s Offshore Personal Survival Course is a 2-day course approved by World Sailing (formerly ISAF). The training requirements form part of the Offshore Special Regulations (OSR) Governing Offshore Racing for Monohulls & Multihulls mandated by many distance racing organizations and provides practical training for offshore cruisers.

I spoke with Diane Reid about the clinic and its value in building the safety ethos in both cruising and racing sailors. Diane said, “The idea of safety as a culture on the boat is something everybody participates in ‘just because they do it’, not because they are being pressed to do it or because they have to do it.”

“How do you get your boat to that point? You start off with by encouraging the full use of the equipment that is listed in the racing rules – all of the equipment that is mandated – because it is the starting point. Then it is really a question of ‘How do you get to the point on your boat where it’s just a natural instinct?’”

Is there a difference between a cruiser and a racer? Diane says the impetus may be different but the result and content are the same. While racers may start off pursuing safety at sea because it is something they must do to meet the checklists for a particular race, cruisers do it because they are going off on a big adventure and they see an article or promotion about Offshore Personal Survival Course that tells them there is another opportunity for them to learn. The result is that both are getting the same content and the same value from the workshop.

Is there a difference between a cruiser and a racer? Diane says the impetus may be different but the result and content are the same. While racers may start off pursuing safety at sea because it is something they must do to meet the checklists for a particular race, cruisers do it because they are going off on a big adventure and they see an article or promotion about Offshore Personal Survival Course that tells them there is another opportunity for them to learn. The result is that both are getting the same content and the same value from the workshop.

World Sailing and the Offshore Special Regulations (OSR)

According to the World Sailing website, “The OSR is republished every two years and the latest edition is for 2020-2021 with updates in January 2021. These rules specify vessel construction and safety equipment requirements for catamarans and monohulls for number of race categories.” Download it and view (the regulations and) interpretations of the World Sailing Special Regulations Sub-Committee”.

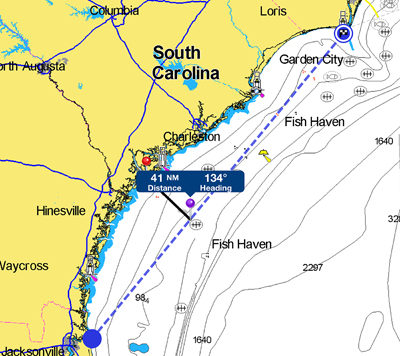

As a coastal cruising sailor, I have rarely thought of myself as being ‘offshore’. But looking at the OCR’s five categories of offshore, I find myself with a new perspective and in hindsight, there were a number of times heading south and back, I should have approached a few situations differently. The key differentiator in these categories is the expectation of outside assistance.

While cruising from Lake Ontario to the Bahamas and back, I carried Boat US towing insurance. I was rarely out of VHF range (line of sight for 30 – 40 NM). Near shore, we were usually able to make contact by cell phone. I also added a DSC (Digital Selective Calling) equipped VHF radio to the boat and took the DSC endorsement for my ROC-M (Restricted Operator Certificate – Maritime). On our second trip, we added a personal EPIRB Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) and AIS (Automatic Identification System – for identifying other vessels) through my VHF radio.

While cruising from Lake Ontario to the Bahamas and back, I carried Boat US towing insurance. I was rarely out of VHF range (line of sight for 30 – 40 NM). Near shore, we were usually able to make contact by cell phone. I also added a DSC (Digital Selective Calling) equipped VHF radio to the boat and took the DSC endorsement for my ROC-M (Restricted Operator Certificate – Maritime). On our second trip, we added a personal EPIRB Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) and AIS (Automatic Identification System – for identifying other vessels) through my VHF radio.

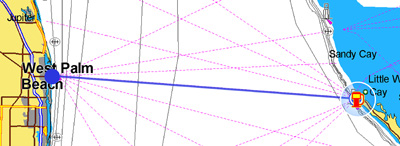

Crossing the Gulf Stream – 55 NM from Lake Worth, FL to West End, Bahamas – we were always within radio range of the US

Coast Guard and the many ships that ply the Gulf Stream heading North and South. In addition, we usually buddy with another boat for any crossing, so if either boat gets into trouble, the buddy boat is close to render assistance or contact search and rescue.

Figure 6 Lake Worth to West End

Returning from my last trip, I decided to cross from Jacksonville, FL to Southport (Fear River), NC. At one point on this 270-NM journey, I was 41 NM offshore and well out of VHF range. I had only my PLB for contact. In retrospect, I should have had a full sized EPIRB and maybe a little more.

To fill in the blanks in my knowledge, Diane Reid was able to breakdown various signaling devices and their use. “When we teach radio certificate (ROC-M), we teach if you are going further offshore, you have to have something that has greater range.” Diane explained that one of the things that she likes to share with people is that there are 3 pieces of kit that people going offshore should consider. From left to right they are a Personal Locating Beacon (PLB), a Man Overboard (MOB/AIS) and an EPIRB.

Diane explained that when people look at the equipment, they think of range. What she and those involved with Personal Offshore Survival would like boaters to consider, is not so much range of communication as much as which type of help are you going to be asking for.

These 3 items are not mutually exclusive. The skipper and lead hand may wear a PLB, while crew – a MOB/AIS device. The EPIRB often resides on the stern rail and is deployed or floats off when the rail is submerged. (I.e. The boat sinks.)

In the World Sailing training standards, Session 14 outlines what is to be covered in Emergency Communications (theory & practical), including emergency procedure words, marine communication options; making a mayday call, VHFs and antennas, Digital Selective Calling (DSC) and AIS, GMDSS (Global Maritime Distress and Safety System) and why it is important; crew overboard alarms, cellular telephone vs VHF, EPIRBs, single sideband; satellite data and voice systems. To understand how these systems function and interact – take a Sail Canada or Canadian Power and Sail Squadron Restricted Operators Certificate – Maritime (ROC-M) course and certification.

Offshore Personal Survival Course

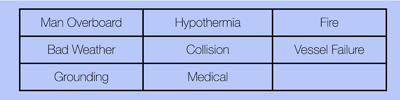

Attending the workshop, I was able to interact with the 12 participants from both cruising and racing backgrounds. This workshop attracts more experienced sailors and facilitates discussions of the more complex issues of sailing further from shore and from readily available outside assistance. The first exercise – Things That Can Go Wrong at Sea – had small groups of sailors listing what could go wrong in the various topic areas they were given:

What equipment would be helpful?

What action would you take?

The participants developed strategies for dealing with the emergencies they were assigned. The authors presented the exercises back to the group, and the participants and course leaders had the opportunity to make comments, ask questions and add insights.

The participants developed strategies for dealing with the emergencies they were assigned. The authors presented the exercises back to the group, and the participants and course leaders had the opportunity to make comments, ask questions and add insights.

I talked with two of the participants (Andy den Otter from Alberta and Dan McKindsey from Quebec) about their experience and both of them mentioned how much they enjoyed the balance between the theory and practical as well as the lecture and participation.

Andy cruises all over the globe with friends and teaches cruising. He chose a course in Ontario because the BC-based courses fill up in a matter of hours. Dan is a marine surveyor and racing sailor who sails out of Collins Bay on the west side of Kingston, ON. The 3 questions I asked of each of them were:

1. Why did you choose to attend the clinic?

2. What was your biggest take away from the clinic?

3. Going forward what will change for you as a result of your experience at the clinic?

Why did you choose to attend the clinic?

Why did you choose to attend the clinic?

Dan: Two reasons. I own a 38-foot racing sailboat and we do a fair amount of long-distance racing. While I have a great deal of experience, and I realize that we do all the things we think we should, you want to double check. The second reason is I want to get my commercial endorsement for my RYA (Royal Yachting Association) Offshore certification and the workshop is a requirement for it.

Andy: After retiring, I spend a lot of time sailing offshore, so I feel I am increasing my likelihood of a problem at sea – just from the time I am spending offshore. I also need the Safety at Sea course to complete the International Yacht Training (IYT –iytworld.com) instructor standard and with the offshore sailing I am doing now – it is a good idea.

What was your biggest take away from the clinic?

Dan: We are going to pay more attention to Man Overboard (MOB). We always have paid attention to it, but I am aware we have not paid enough attention to it. How many times a year do we practice MOB? Once or twice – but that is not enough, and we don’t do it in the worst conditions, so we are going to change the way we train.

Dan: We are going to pay more attention to Man Overboard (MOB). We always have paid attention to it, but I am aware we have not paid enough attention to it. How many times a year do we practice MOB? Once or twice – but that is not enough, and we don’t do it in the worst conditions, so we are going to change the way we train.

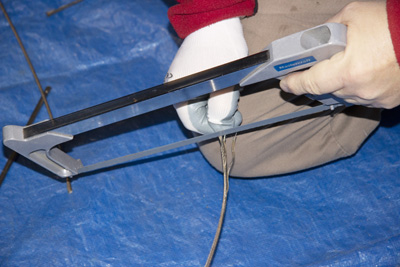

Andy: Cutting the rigging, especially realizing some of the tools didn’t work as well others. The hacksaw was a lot of effort and it took a long time. I have been on boats and, ‘Yea. There’s our bolt cutters.’ But are they the good ones? Do they do the job?

Another take away was the choice of life raft. A 6-person life raft is very crowded with six people in it.

Going forward what will change for you as a result of your experience at the clinic?

Dan: There are things that I noted going through the course that I will address on my own vessel. For instance, I have 5-pound fire extinguishers. During the course we used 10-pound fire extinguishers and they did not last very long, so a 5-pound will last even less. I am going to change all my fire extinguishers to 10-pound.

We are also going to add some dedicated Man Overboard (MOB) retrieval equipment. We have a LifeSling® and we are going to add a parbuckle to retrieve an injured person from the water. A third item is rig cutters. “I have rod rigging and it became obvious that I am never going to cut rod rigging with any standard cutter, so I am going to have to get a hydraulic cutter.”

Andy: Getting into the pool with all of our foul weather equipment on and struggling to get into the life raft. I am still fairly agile, but I sail with all sorts of other people (body size and conditioning). Getting into a life raft is going to be a challenge with some of the people I sail with. To improve their probability of success in boarding a life raft is dependent on wearing a life jacket. On one training cruise we did a sailing risk assessment and it was interesting how many of the risks we might encounter, were minimized by wearing a PFD. I have always practiced that, and I will continue to build that safety ethos in all of my students and guests.

(Visit Just-Marine.net for more information on parbuckles and how to use them. Also review this YouTube video)

Although this article has referred to sailing and sailing organizations, the material in the Offshore Personal Survival Course is perfectly suited to power boat cruisers as well. With the exception of possibly the rig cutting and storm sails, we sail in the same water, travel the same distances offshore, encounter the same weather and use the same safety gear, communication equipment and life rafts.

I think that it is only fitting that I give the last word to the one who has patiently and passionately worked to build a Culture of Safety throughout her career – Diane Reid. “At the end of the day it’s about when you have that moment where the boat’s going down out from underneath you, and you’re thinking, ‘Oh! I wish I had taken a course on what to do here – I am not sure what to do’ versus ‘Oh! I was actually able to prevent an actual catastrophe because I got a little more education on what I am doing, and I am feeling good about this not so great moment right now’.”

For Safety at Sea Courses contact your provincial sailing association.

Ontario Sailing has open registration at ontariosailing.ca/registration-forms/

“Safety – more than a list – make it a way of life!”

2504 words