Blind Channel Resort

One of my favourite places

By Marianne Scott

Sailing north of Desolation Sound, the Discovery Islands and the Broughton Archipelago offer cruisers a bevy islands with ample anchorages. Tides cause swift currents to run through the islands’ waterways. Few marinas are found in this large, sparsely populated region but one that provides all the services boaters need and especially enjoy is Blind Channel, a marina and resort operated by the Richter family located on Mayne Passage on the east side of West Thurlow Island (50 24. 82N, 125 30. 00).

My husband, David, and I have visited the marina several times and have always appreciated its hospitality. I’ve particularly looked forward to the excellent restaurant after cooking aboard for weeks. We tied up at one of the 36-metre docks—a good size for berthing two medium-sized boats. It makes for a communal atmosphere when boaters catch each other’s mooring lines and conversations flourish.

Power up to 50 amps is available and the fuel dock has gasoline for dinghies, diesel for your boat and propane for the galley. You can refill your water tanks with clean water without tannin. The whole area is tidy and organized. You can shop, dine and hike. And it epitomizes a history of entrepreneurship, daring and do-it-yourself boldness.

The Marina/Resort isn’t the first enterprise to occupy this rare piece of flat land—among the many steep islands where trees grow right down to the waterline, it’s one of the scarce coastal places where a lifestyle or business can thrive.

People discovered it early: West Thurlow lies in the traditional territory of the Kwakwaka’wakw. In 1792, Capt. George Vancouver named the island for Edward Thurlow, the powerful Lord Chancellor of England at the time. Only later it was discovered that Thurlow is not one, but two islands. The narrow passage between them was called “Blind Channel,” perhaps because Capt. Vancouver had missed it (it was formally named Mayne Passage in the 1860s). Since then, the property has been home to a sawmill, salmon cannery and saltery, shingle plant, boat builder and marine repair facility.

That was until the family patriarch, Edgar Richter, spotted the “for sale” sign in 1969 when cruising with his wife Annemarie, and offspring Philip, Trudy, Alfred and Robert, in his hand-built, 30-foot wooden boat, Pamar. Edgar, an immigrant from Germany, was enthralled by its potential, although the place was a mess. Heaps of debris, a decrepit store and shacks left behind by the previous industries were scattered around the property. Barrels of fuel occupied the rickety dock needing a hand-pump to dispense their contents.

It took a while before Edgar was able to persuade Annemarie that building a marina in this isolated and rundown place would be a great opportunity, especially as Edgar, a meticulous craftsman, had built a special family home in Vancouver.

But by 1970, they’d bought the property and have continually improved it for nearly half a century. They laboured hard, especially in the early days.

“We began cleaning the place up with a wheelbarrow, a pick and a shovel,” Edgar told me. “There were container loads of old bottles. Metal junk. Rotten stuff on the beach. We dug a

hole and buried a lot of it where the patio is now. Hard, backbreaking work. The old-timers who lived in shacks around here had a bet we wouldn’t last a year. They’re all gone now, many of them died fairly young. Too much boozing, you know. I’ve outlived them all!”

Slowly, the couple and their growing children added homes for themselves, cottages and service buildings. A generator was installed and proper tanks replaced the barrels of fuel. Today, many people come here not only to the marina but to stay in the cottages and taste the freedom of the splendid outdoor setting. They can mail an old fashioned letter at the post office and perhaps receive a few emails—when the satellite isn’t having a temper tantrum. Thus, an unplugged, true holiday is a wonderful possibility. For us, the store has been a godsend after a few weeks of sailing when our provisions were running low. The chance to do laundry is another bonus.

Annemarie Richter, the mater familias, spent many years making mosaics out of found objects—bits of broken pottery, shells and interesting pieces loyal customers brought her. Although she died 16 years ago, her art lives on, embellishing the docks and the Cedar Post restaurant; it’s fun to think about how she put discarded stuff into such amazing patterns. Edgar, 92, still lives in his red painted house, filled with mosaics and the beautiful furniture he carved from fine-grained, old-growth fir. His son Philip and grandson Elliott manage Blind Channel supplemented by crew. They continue improving and adding to the cottages. A fourth generation of youngsters is sprouting on site.

I was pleased to find Blind Channel’s three excellent hiking trails to exercise my boat-bound legs. They range in length from one-quarter mile to about a mile. The first and shortest takes you to a lookout over Mayne Passage, the second leads to a gigantic cedar, while the third introduces the “Forest Management Trail” with forests that have been logged, replanted and regrown between 1885 and 2008. This trail gives a good idea of the various stages of forest regeneration after being clearcut.

We chose the big cedar trail; this path also gives a good idea of a forest in transition. The trail rises about 200 feet through trees that are about 90 years old. Stumps from that period still remain and are much taller than stumps left behind today; some carry the cut marks where fallers inserted planks on which they stood while sawing. A couple of mature trees have hollows between their roots—they’ve matured on top of a nurse log and sent down roots while the old trunk slowly rotted away.

I took a long time to amble along this relatively short trail—there’s so much to see. Some older trees were toppled by strong winds and lie with their wide, flat root systems high in the air. During their period of decay, which can last hundreds of years depending on size, they provide a platform for new trees, mosses, shrubs and ferns, as well as nourishment for billions of microbes and animals. That’s why they’re called “nurse logs.” It’s wet enough—about one-and-a half metres of rain fall here annually—that some of these “blow downs” host remarkable funguses, some hard as wood, some soft and spongy, with many color bands. I tasted a few huckleberries the bears had missed. For me, it’s stopping and smelling the mosses.

We ran into another couple returning on the trail who said they’d startled a young black bear that took off. We were not so lucky—or unlucky—depending how you feel about sharing a trail with bears.

The Big Cedar is massive. As we posed for photos in front of the mighty trunk with its vertical bark and broad roots, we looked puny. It’s thought the tree is at least 800-years-old. The Richters have attached a brass plaque: “Annemarie Richter, 22 March 1924 – 20 November 2003 / Annemarie was devoted to harmony, beauty and the joy of good conversation.” A wonderful tribute. It makes you feel part of a community of people, trees and nature.

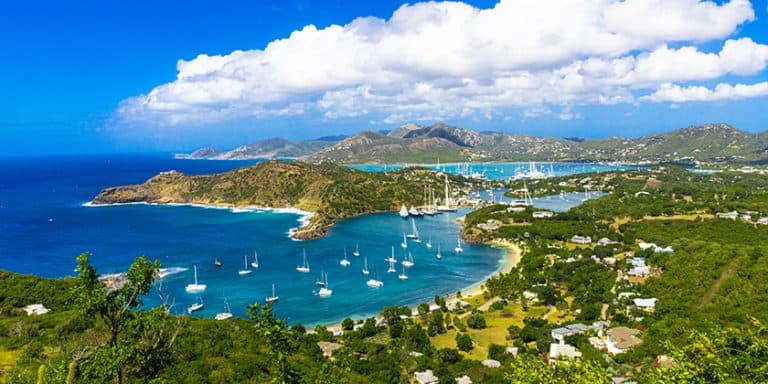

Aerial view of Blind Channel Resort. Photo Jess Cavanagh

Aerial view of Blind Channel Resort. Photo Jess Cavanagh

After our hike, I went berry picking, amazed there were so many and I was the only one collecting. I gathered a bunch of huckleberries to add to the pancake mix the next morning, found a patch of fat ripe blackberries and felt deeply satisfied to have gathered a bit of my own food.

Later we readied ourselves for the much anticipated dinner. Edgar had told me that in earlier times, dinner was served at his home. “Annemarie cooked traditional German dishes,” he said. “We could seat 35 and it was a great success. People liked the homey atmosphere and they’d linger while other diners sat on the staircase and lawn waiting to get in. The kids and I were the wait staff. Our food’s early popularity led to our building the restaurant.”

In the summer season, the Cedar Post serves breakfast, lunch and dinner. Jennifer Richter, married to Phil, bakes bread, and manages the garden where herbs and produce are grown. This is truly local. We joined other boaters on the patio for a pre-dinner drink, telling tall tales of our adventures on the ocean, or sharing yet another story of some boat issue needing repair.

The dinner menu offers locally caught spot prawns, salmon and halibut, a good steak, and the kind of food Germany is famous for—schnitzel, rouladen and kaes spaetzle. We tucked into dinner and drank some lovely wine. Some of the Richter family helped serve the food and took time to chat with the diners.

We like Blind Channel and its friendly atmosphere. After a period of cruising and anchoring, having a dock—and forest paths—under your feet is a fine respite.

If you go: reservations are recommended. VHF 66a; 1-888-329-0475 or 250-949-1420; info@blindchannel.com; blindchannel.com.