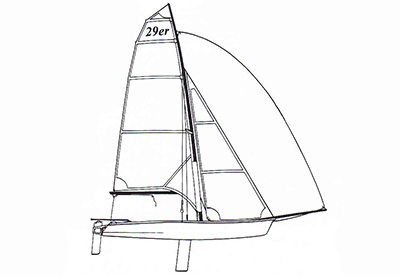

29er

“The 29er will be to sailing what snowboarding was to skiing,” says the boat’s co-developer Ian Bruce. He and others, who have already tasted the 29er’s performance, enjoy the rebel-yell style of this boat. With its almost non-existent stability at the dock and its 20-knot sailing speeds, it is not for the sedentary sailor; athletic types looking for an adrenaline-rush will absolutely love it.

Why design a boat for this specific group of sailors? Well, for Julian Bethwaite backed by his father Frank, English designer Dave Ovington, Japanese designer Takao Otani, and Canadian details-man Ian Bruce, it ‘s quite simple. The 49er, the high performance big cousin of the 29er, was recently granted Olympic status for the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia. That decision was immediately followed by the question: “How are young sailors going to train for this boat?” The 49er is too complex a boat for smaller novice sailors to jump into, and the untrapezed Laser and comparably low-powered Laser II are inappropriate training vessels. The 29er, however, bridges the gap perfectly and its creators are not bashful about claiming that it is a boat for those with big dreams and above average skill levels.

The hull shape of the 29er is nothing like the common fare at the local launching ramp. As you move aft, the narrow rounded sections in the bow end flatten out to gently curved sections. Chines develop about halfway along the length of the hull to give the water a natural point to break clean when the boat planes – and it will spend a lot of time planing. The interior is clean, smooth and contoured.

The 29er had the luxury of an ideal development schedule – two years of drawing, prototyping and testing, with significant changes along the way. Between the first and fifth prototype, the floor height of the self draining cockpit was raised to keep the boat drier, the hull was extended in length and slightly in width aft to increase the weight capacity, and the rig was reduced in size for manageability by smaller crews. Initially the larger rig was designed to keep the speed in the supersonic region, but it put the boat out of the range for the youth sailors it was intended to serve, so the area of the sail plan was reduced.

Surprisingly, the smaller rig turned out to be faster. It just doesn’t sound logical, does it? I have seen this happen before. It ‘s understandable that the smaller rig is faster in heavy air when one wants a more controllable, less powerful sail. But how could it be faster in light to medium air? Well no one is quite sure, but I recall that in the days of 12-metre America’s Cup boats that the spinnaker size was unlimited -as long as you could hoist it up and fly it from the pole it was legal. The temptation was to go very large, but racers soon discovered that the fastest spinnakers were not the largest sails. The suspicion was that the larger sail did not present as efficient a sail shape. 1t was also heavier physically and therefore did not lift as well in light air. Something of the same phenomenon may be happening with the already large asymmetrical sail on the front of the 29er. There’s a limit to what will fly well, be controllable and fit between the end of the sprit and the hoist on the mast.

Early boats for North America were either built in England or Australia, but new tooling is now being prepared for production in Montreal. Bruce’s shop, which also builds the popular Byte, will pump our four boats per week to the tightly controlled class specs. Those specifications keep the hull construction material to fibreglass cloth (no carbon fibre or Kevlar) with polyester resin, for easy repairs at the sailing club. Watch for these spectacular little boats and future Olympians to go screaming by the docks of a high-performance sailing club near you.

Originally published in Canadian Yachting’s Summer 1999 issue.

Specifications:

Length 14.6′

Beam 5.8′

Weight (unrigged) 155 lb.

Rigged 185 lb.

Sail Area (jib and main) 135 sq. ft.