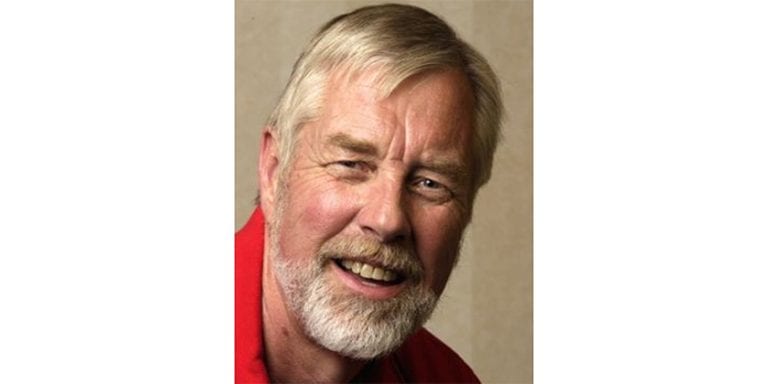

Gregory C. Marshall. Canadian Naval Architect and designer par excellence.

Text and photos by Marianne Scott. Yacht and boat images courtesy of Greg Marshall Naval Architect Ltd.

I am standing in the middle of a high-ceilinged space beside renowned naval architect Greg Marshall and two of his team, Sara Baker and Lachlan Palmer. All of us are wearing Microsoft hololenses. Lachlan makes a move and suddenly, a virtual, white MTU engine appears in front of me. A valve floats next to it. I stretch out my hand and jerkily move the valve to a fitting on the engine.

This is a new optical recognition technology that Gregory C. Marshall Naval Architect Ltd. (GCMNA), whose Victoria B.C.-based company designs both luxury yachts and commercial vessels, is developing. It’s a software program that will allow a boat builder’s crew to know virtually—and exactly—where the vessel’s every item should be sited and which parts go where. Through this virtual reality software, the installer can connect with the designer or engineer and discuss any issues that inevitably arise. The software, which Greg expects to be completed in the next two years, is specifically designed for yachts and commercial boat construction and will streamline the design timeline. “It will replace the drawing process,” he says. “It’ll be a huge time saver.”

“We tested our hologram software on a new Westport 125 engine room,” he continues. “We could see the changes the boatyard had made. Moreover, in an-under-construction 112-footer, we noticed what they missed. Using the hololens, we can see what’s not there in seconds.”

Combining the hololens with a 360° fisheye camera allows for inspections of spaces that were not visible before. “In a Tuzla, Turkey, boatyard, where one of our designs is being constructed, I performed a safety check from Victoria on a tank’s interior using the headset while my eyes directed the camera,” he says. “I could see if the coating was properly applied, the welds secure, and the valves tight. Throughout the inspection, I’m talking on the phone with the Tuzla crew.”

Greg Marshall began drawing boats as a toddler and doodled them on blackboards throughout his schooling days. As the custodian erased the drawings, Greg would start anew the next day. He devoured glossy yachting magazines. Noting Greg’s interests, his architect dad, Donovan Marshall, introduced his son to distinguished boat designer Bill Garden, who lived and worked on a small island near Victoria. Garden invited Greg to do some drafting. “Bill told me that my compulsion for big yachts wouldn’t last once I saw how complicated they were,” Greg recalls.

To complete a large yacht requires originality, creativity, styling, space and interior design, engineering, balance and ballast calculations, composites, mechanical and electrical systems, joinery, propulsion, and business savvy. The yacht must exceed classification societies’ standards that cover a yacht’s hull, engines and key safety systems. “Despite what Bill said, I liked big yachts right from the first,” says Greg. “After I arrived on his island, I enthusiastically drew a real yacht and although it was never built, this first experience launched my eventual career.”

During the summers, Greg worked for Garden, learning about design and customer relations. During the winters, he studied naval architecture at Newfoundland’s Memorial University, graduating in 1984. He then rejoined Garden’s firm until the designer sent him to work up some styling concepts for an 80-footer for Ed Fry, a boat designer in Houston. “I thought I’d work with Fryco for a month,” Greg says. “But I ended up buying into the company and staying for eight years. Ed designed commercial boats, I drew the yachts. Our partnership was terrific, but after a Vancouver Island holiday, I realized Houston’s 100°F temperature and 100 percent humidity were too much.”

He returned to Victoria when an opportunity came up to design aspects of Pacific Mariner’s 65-footer, a yacht builder in LaConner, Washington (now part of Westport Yachts).

After first working out of his dad’s office, and as his commissions multiplied, Greg found a 1930s farmhouse with an apple orchard on Victoria’s outskirts. 22 years later, he’s still there. “In our electronic world, we can work anywhere,” says Greg. (During the pandemic, two-thirds of GCMN’s 31 staff worked from home.)

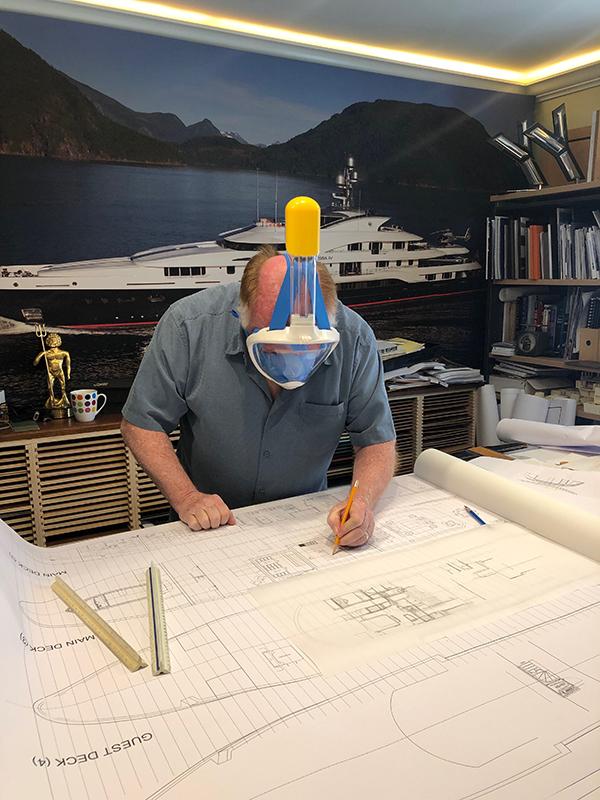

The farmhouse turned out to be the perfect design office—ample free parking, a quiet atmosphere, a badminton court for stress relief, grazing deer, and a field for walks when the team’s eyes grow weary from the intense computer work. Every room, including the kitchen and basement, became a workspace. Greg still works with business partner and naval architect Gordon Galbraith on the drafty front porch which only recently got heating. Greg is hardy—I’ve seen him outside in shirt sleeves, in pouring rain, talking volubly on his phone.

Since Greg hung out his shingle, the company has designed about 2,100 boats, with 300 measuring more than 100 feet. As the firm’s international reputation strengthened, the yachts grew bigger and more complex. Various design softwares, 3D modelling and instant communications with clients and builders became ever more important, not only in the design process, but for working collaboratively. “With modern communications, clients, our design team and the boatyard can be anywhere in the world and a modification can be updated, shared on-line and sent in seconds,” explains Greg.

Yet when a new yacht is commissioned, Greg reverts to that schoolboy who drew by hand. “I still hand-sketch the initial outlines, space concepts, layout and styling”, he says. The drawings are scanned and then Gordon and the other crew execute the highly complex calculations of balance, ballast, weight, and the mechanical and electronic systems needed to build the floating palace. To perform these tasks, Greg has recruited a specialist team including not only planners and engineers, but also a holographic expert, a Ph.D. in AI, and a chemist who analyzes materials and judges their environmental impacts. “To create an holistic yacht that satisfies an owner’s dreams, demands a balance of art and science, of creativity and technology, of appearance and performance,” he explains.

To accomplish this balance, the team keeps up with ever newer technologies. A 3-D printer, located in the recently built structure next to the farmhouse, had just banged out a cabin layout; smaller parts are produced by a tiny printer. Eventually, 3D printers will produce complete megayacht hulls.

GCMNA is developing optical recognition software will replace the QR code, which currently identifies parts. The software will recognize the manufacturer and the part’s number, cost and weight. It’s a way of keeping the books and a method of continually calculating weight distribution; important for a boat’s balance.

GCMNA recently provided space planning and arrangements for an innovative diesel-electric vessel, the 80-metre Artefact, built by Nobiskrug in Germany. “It can operate on electricity,” says Greg. “No noise, no fumes. Less vibration. Thus, leaving a marina, the electric yacht lowers local pollution.”

Artefact is also capable of dynamic positioning, which, the Nautical Institute explains, uses “a computer control system that automatically maintains a vessel’s position and heading by using her own propellers and thrusters.” To maintain the positioning, the yacht is fitted with an azimuth thruster, an array of propellers that can be turned to any horizontal angle and make a rudder unnecessary. Wind and motion sensors, as well as gyrocompasses, inform the computer of the vessel’s position and the environmental forces affecting it. Advantages? A yacht can maintain its station without throwing an anchor on, say, a coral reef. This “virtual anchor” can hold a vessel in place while waiting at a fuel dock, maintaining a fishing location, or supporting underwater research.

Nevertheless, not even tested technologies always work as planned. A yacht under construction received $2.5 million worth of windows—laminated glass held together by liquid resin. Disaster struck, when a manufacturer’s bad batch of resin tinted the windows cranberry pink when exposed to sunlight. “All the installed windows had to be cut out of the woodwork and new glass installed,” says Greg. “The yard also faced a $10,000-a-day late penalty. We’d been researching electrochromic windows, a technology that can prevent excessive solar heating inside a yacht. But this mishap has made us very cautious.”

Before starting a design, the team makes efforts to get to know the client before Greg even hand-sketches the basic outline of the yacht. “We like working with the owners and their unique personality and translating it into a boat,” says Greg. “Do they want to wake up to sunrises? How many guests do they want aboard? What are their hobbies? Do they work aboard a yacht? What kind of offices are required? Do they need a nanny suite?”

As a result, the yacht can be sized up or down, become more or less opulent, concentrate on energy efficiency and range, have a trawler-like profile, or look ready for space travel. “One client has a dog prone to seasickness so we’ve designed a gyro-stabilized dog bed for their pet,” Greg says. Another client, who lives in parts where piracy is common, asked Greg to make his yacht look ugly to lessen chances of attack.

Over the years, GCMNA has designed entire yachts—or portions of them. Designs include the Westport 112 and 130 and a 50-metre for Vancouver’s Crescent Yachts that is now under construction. He designed the San Juan 38 and 48, sometimes called “picnic boats,” or “the little Gatsby.” Trawlers, 34-metre displacement expedition yachts, power catamarans, refits, cold-moulded boats—even a powerboat with a sail—all these have left the firm’s drawing board. They’ve worked with such international boat builders as Burger, Taiwan’s Ocean Alexander and Horizon, Westport, Christensen, German yard Nobiskrug, and New Zealand’s McMullen and Wing. GCMNA also designs for such Canadian builders as Neptunus, Coastal Craft, Kanter Marine and Park Isle Marine. Presently, Vancouver-based Crescent is building a glamourous GCMNA-designed 164-footer.

GCMNA’s designs have won a batch of prizes, including the World Yachts Trophy, the International Superyacht Society Design Award, and the Asian Boating Award. Winning vessels including the 34-metre VVS1 and 45-metre Big Fish. They’ve also won the engineering trophy for Best Refit at the World Superyacht Awards for Attessa IV, Seaspan president Dennis Washington’s 100-metre yacht. In 2021, GCMNA’s 80-metre Artefact won nearly every major award available.

Yet not all has been smooth sailing for GCMNA. The 2008 market crash cancelled a dozen yacht projects. “We wanted to survive,” Greg says. “It turned out commercial boats came back faster and saved our bacon. We diversified and developed our commercial boat design side. It’s become a good source of cash flow. We’ve been refitting Coast Guard ships, and designing workboats, water taxis, landing craft, patrol boats and passenger vessels. We have specialized teams who produce designs that can be built efficiently with our repeat clients, unlike the big yachts that can take years to complete. Diversification has been great.”

Just as this article went to press, British Columbia announced a grant of nearly $1 million matched by GCMNA to develop a 40-foot zero-emission catamaran. “It will be an all-carbon, electric vessel with hydro foiling which can be used for transportation, coastal patrolling, and eco-tourism,” Greg says.

Over the coming years, Greg, now 60, intends to design ever more “super-intelligent” yachts of all sizes. But he’s also booking some time away from the office, although he’s not retiring. A local yard is restoring a 65-foot wooden Bill Garden design, Zest, which will serve him, his family and friends on cruises as far as Mexico. “Gord (Galbraith) and Matt (Dilay) and I work seamlessly together and I never worry when I’m gone chasing new work,” he says. “For the next decade, I’ll hunt for new business bringing it home to the team who then take over.

“From long experience, I know that during the fall, I’ll need to work like a maniac and that from January to May, I’ll shape and perfect that work. Summers, I’ll cruise, though I’ll always be available to my crew. Yacht design continues to be exciting, challenging and fun. My greatest success as a naval architect is that after all these years, I still love going to work.”