Kirby 30

Story by John Turnbull

Photos by Ted Romer

Not your average thirty. If you need standing headroom. forget it. But if you love to sail, and sail fast.

“We wanted to design a pretty little boat that would be fast regardless of rating,” says designer Bruce Kirby.

“it’s a boat whose aggressive looks will intimidate 75 per cent of the market,” says builder Dick Steffan, head of Mi-rage Yachts of Pointe Claire, Quebec.

This isn’t the classic story of a designer unable to curb his racey tastes and a builder faced with selling to a cruising oriented market. Kirby and Steffan agreed on the concept, developed it together and are about to share the success of the Kirby 30 among those 25% of sailboat buyers who just aren’t interested in the average “racer/cruiser.”

“There are so many 30-footers around these days that sleep five and have six-foot headroom, but just can’t be made to go fast because the cockpit’s too small and the deck ‘s too narrow or their too heavy,” complains Kirby. “The decision was to go with simple, light and practical accommodations, and to make the boat a really fine sailing platform.”

“My personal interest,” says Steffan, “is how well the boat balances and steers. We didn’t want a fast boat with a lot of peculiar habits, we wanted a fast boat that could easily be sailed up to its potential.”

“My personal interest,” says Steffan, “is how well the boat balances and steers. We didn’t want a fast boat with a lot of peculiar habits, we wanted a fast boat that could easily be sailed up to its potential.”

Have Steffan and Kirby succeeded? We drove down to Mallets Bay on Lake Champlain, just north of Burlington, Vermont, to find out. One of Mirage Yachts’ new dealers, The Moorings, had a K30 at the dock. It had managed to attract some attention with its performance the previous weekend in a local overnighter. It hadn’t won the race – that honour went to former Canada’s Cup winner Golden Daisy – but it had made a few local dealers of 30-foot stock racers start to worry.

That particular Friday, Mallet ‘s Bay was flat and blue. A steady breeze of about 15 knots drove us across the bay in such a hurry that we had to kill the chute when our photographer’s boat, a 26-foot auxiliary cruiser under full power, couldn’t get near us. We headed back to the dock while arrangements were made to put the photographer in a runabout.

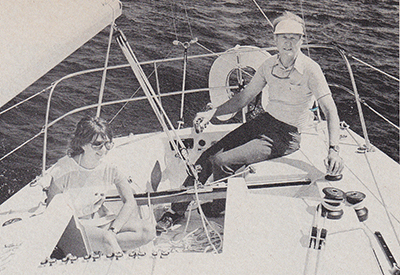

Handling the spinnaker was a pleasure. We had four people aboard and I should probably count myself among the two inexperienced ones – I hadn’t done much sailing by midseason and was wondering whether I’d be much use. It didn’t take me long to feel like a hotdog again (at least nobody complained that I was getting in the way), and some credit has to go to the boat. I wonder how many boat buyers have spent enough time on a foredeck to really appreciate what “a good sailing platform” means? Probably fewer than the 25 per cent who will be attracted by the 30’s appearance. You don ‘t have to thread your way forward on the Kirby, around the cabin and the shrouds. In fact, the proportions of the cabin make it seem as if it’s there to provide a solid footing. The decks are wide and flat and, just as important, clear of turning blocks and lines.

Handling the spinnaker was a pleasure. We had four people aboard and I should probably count myself among the two inexperienced ones – I hadn’t done much sailing by midseason and was wondering whether I’d be much use. It didn’t take me long to feel like a hotdog again (at least nobody complained that I was getting in the way), and some credit has to go to the boat. I wonder how many boat buyers have spent enough time on a foredeck to really appreciate what “a good sailing platform” means? Probably fewer than the 25 per cent who will be attracted by the 30’s appearance. You don ‘t have to thread your way forward on the Kirby, around the cabin and the shrouds. In fact, the proportions of the cabin make it seem as if it’s there to provide a solid footing. The decks are wide and flat and, just as important, clear of turning blocks and lines.

Getting the spinnaker set up and drawing was simple. This was at least partly because on a fractional rig, it isn’t very large, but also because while two people sailed the boat, the other two had room to get past them with coils of sheets and halyard. Even with the running backstays leading into the cockpit, I never felt the sheet-handler’s common frustration of too damn many strings, and too many people sitting on them.

The layout of the cockpit helps a lot in that respect. I never found the lack of combings to be uncomfortable, though some might, but I did find that, especially when moving around the cockpit or working in a half-crouch, as you so often do, the flat deck-level edge to the cockpit was really a help. It’s just high enough to prevent water from draining onto the cockpit seats, but not high enough that you have to step over it. Where the helmsman sits, this slight edge is just right for hooking your rear end so that, when steering to windward on the high side, you don ‘t have to brace your feet – no small consideration when you’re doing stints several hours long at the helm.

The layout of the cockpit helps a lot in that respect. I never found the lack of combings to be uncomfortable, though some might, but I did find that, especially when moving around the cockpit or working in a half-crouch, as you so often do, the flat deck-level edge to the cockpit was really a help. It’s just high enough to prevent water from draining onto the cockpit seats, but not high enough that you have to step over it. Where the helmsman sits, this slight edge is just right for hooking your rear end so that, when steering to windward on the high side, you don ‘t have to brace your feet – no small consideration when you’re doing stints several hours long at the helm.

The slightly raised steering seat also allows the helmsman to see over the heads of his busy crew, avoiding the situa-tion I’ve so often felt myself (and I’m tall) in which everybody is warning of some impending disaster, in their own incomprehensible style, and they’re all too excited to sit down and let you have a look.

One other point before I leave the deck layout; that contrasting colour extrusion that sets off the shape of the deck so nicely in most “racing” boats has been mercifully omitted on the K30. The skipper can ask the crew to get their legs over the side and hold the boat down, and still be confident that when they’re needed again they won’t all be convulsed with “pins and needles” while their circulation re-establishes itself.

One other point before I leave the deck layout; that contrasting colour extrusion that sets off the shape of the deck so nicely in most “racing” boats has been mercifully omitted on the K30. The skipper can ask the crew to get their legs over the side and hold the boat down, and still be confident that when they’re needed again they won’t all be convulsed with “pins and needles” while their circulation re-establishes itself.

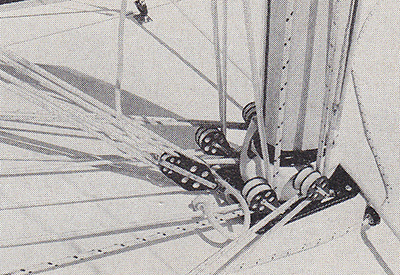

The fittings were all of excellent quality and there were enough of them. I won’t try to run through the standard equipment list, but be assured the boat is set up to race off the dock. Dick Steffan is a racing man himself, with a background in the Soling class, and he knows where things should be. The blocks are Harken and the mainsheet assembly, including the track, is also Harken. The backstays, usually a pain in the neck on a stock boat, are neatly set up with a shock-cord retriever that pulls the leeward stay up out of the crew’s way. The layout of the fittings seems fine to me, though I’m sure that, after a few days aboard the boat, I’d want to move this or that as everyone does. However, the boat is intended for one-design and it’s been thought through with appropriate care.

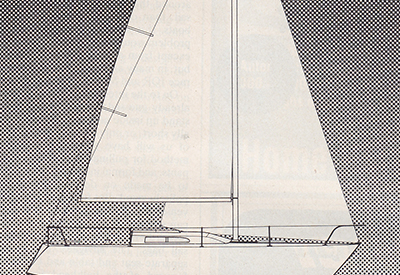

The rig is fractional, of course. Someone was heard to remark, as we were playing with the draft position in the headsail, “Once you’ve raced a fractional rig, masthead is just boring.” True enough. Power is in the mainsail, which can be shaped more easily; the headsail is lighter to trim and quicker to tack; the spinnaker, as I mentioned earlier isn’t a monster when the breeze gets up; you can play with the spar bend and pull strings to your heart’s content, and they all do something. With the permanent and running backstay controls plus the main traveler within reach of the helm, the helmsman can fuss away until his steering balance and drive in both sails is just what he wants. (And when he’s all finished you can tell him someone just sailed through his lee.)

Steffan has chosen a new Canadian spar builder: Cinkel of Toronto. Actually, Cinkel has become the only Canadi-an spar builder since they expanded their manufacturing business from steering gear and other fittings. By Steffan’s admission, the Cinkel spar is a close imitation of the French Isomat. (I thought it looked familiar.) It seems as if all the Isomat’s best qualities have been maintained. For example, the fittings and casting designs are first rate, and some of them are quite innovative. The spinnaker car is a simple plate, running on plastic bearing surfaces in an integral mast track designed right into the extrusion. It moves under load like no other spinnaker car I’ve tried to adjust on a beam reach. The gooseneck is an elegant ball and socket that comes apart with the removal of one hefty spring clip, and the other fittings are of similar design quality.

Steffan has chosen a new Canadian spar builder: Cinkel of Toronto. Actually, Cinkel has become the only Canadi-an spar builder since they expanded their manufacturing business from steering gear and other fittings. By Steffan’s admission, the Cinkel spar is a close imitation of the French Isomat. (I thought it looked familiar.) It seems as if all the Isomat’s best qualities have been maintained. For example, the fittings and casting designs are first rate, and some of them are quite innovative. The spinnaker car is a simple plate, running on plastic bearing surfaces in an integral mast track designed right into the extrusion. It moves under load like no other spinnaker car I’ve tried to adjust on a beam reach. The gooseneck is an elegant ball and socket that comes apart with the removal of one hefty spring clip, and the other fittings are of similar design quality.

I wish I could be as enthusiastic about the section itself. It seemed to perform well, as far as I could make out, but I have to agree with Kirby that, as a wide diameter, fairly thin-wall section, it runs against current theory both from a structural and operational point of view. (See Backyard Builder, August and September, 1980, for a discussion of the engineering.) I’m not suggesting that it’s going to fold itself up, but it does present a larger face to the flow of air around the mainsail, the chief driving sail, than other spars on similar sized boats. If it were a one-design class, the problem wouldn’t be worth considering, except from a structural point of view, but, in many are as, the K30 will have to race IOR and MORC.

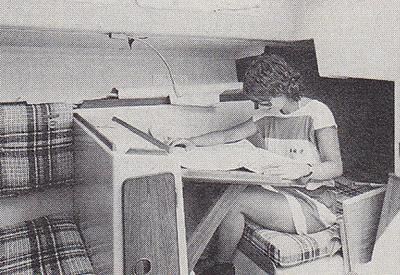

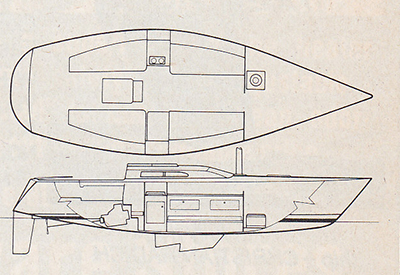

On to the interior. In case you haven’t already guessed, you won’t be able to stand up inside unless you’re exceptionally short, or only 12 years old. The rest of us will have to use the two-stage method for pulling on our foul weather pants, and formal introductions will have to be made on deck where we can politely stand. But for those two inconveniences, the interior is roomy – you can stretch, sit up and make your way forward even while the sole is piled with sail bags. The navigator has his own separate seat and table and the head is forward of the bulkhead for anyone who likes to get away from it all. There’s a galley, but there’s no stove. If you’re serious about eating hot meals (and anyone who races more than 50 miles usually is), you will have to install a gas stove or a Sea-Swing-type gimballed burner.

Kirby’s intention was to provide “enough interior to satisfy those who mostly day-race, but who like to spend the occasional night aboard, and the serious racer who must be able to sleep two to windward, navigate efficiently and cook simple meals.” He’s achieved that, and it doesn’t look like a teak palace.

Kirby’s intention was to provide “enough interior to satisfy those who mostly day-race, but who like to spend the occasional night aboard, and the serious racer who must be able to sleep two to windward, navigate efficiently and cook simple meals.” He’s achieved that, and it doesn’t look like a teak palace.

Construction generally is simple and solid. The glasswork is excellent wherever it’s exposed, which is almost every-where, and Mirage has a good reputation in that area. The tooling was done by Henry Adrianse at Niagara Nau-tique in Niagara-on-the-Lake, and it seems to be fair and crisp throughout. No attempt has been made inside to mask the fact that it’s a plastic boat. The edges are finished in a simple flexible bead, and interior woodwork is minimal and standard quality.

Auxiliary power is provided by a fairly heavy Yanmar diesel. A light gas motor was Steffan’s choice, “but you just can’t sell a boat these days without a diesel engine.” Its weight and the placement of the fuel tank is still a source of some concern to Kirby, who feels that the boat’s bow-down trim, essential to a low IOR rating, is com. promised by the weight in the aft end. Placing the tank further forward, he claims, would solve the problem.

One other compromise was the shallow draft. A typical IOR base draft for a 30 footer would be about five feet, nine inches. The K30 draws five feet. Apparently this is partly the result of pressure from an influential potential owner on Lake Simcoe. “I think I got an extra inch in there without their knowing it,” says Kirby, “but the shallow draft doesn’t seem to be a problem. I’m using a new keel section.” (This, citing a designer’s prerogative to business secrets, he declined to describe.) “It proved out well on my last four boats and is working on my latest, a 40 footer.” In the meantime, if you sail on a shallow body of water like Lake Simcoe, you’ll be able to run aground that much closer to shore.

As to speed, I’m going to have to let the early race results tell the story: with Hans Fogh aboard for a maiden race at Annapolis in May, the K30 walked away from a fleet which included much longer boats, some very well sailed. That was in heavy air with a lot of surfing. Kirby has backed up claims that, in lighter air, the boat performs along-side a well sailed One Tonner. It certainly felt fast while I was sailing it, but with nothing to sail against, and not trusting anybody’s log, that’s as far as I’ll go. In a gust, going to weather, it didn’t have the “lay-over-and-struggle” habit that is so common among boats with pinched ends. It just lay over and went faster. After one on-purpose broach, it made a quick, automatic recovery and accelerated out. Each sheet adjustment brought some change in feel. There aren’t many slow boats that give you response like that.

In the end, though, both Kirby and Steffan know that those 25 per cent of buyers who aren’t scared away by the K30’s aggressive appearance, are going to buy it because of its looks. Never mind how fast it is, how easy to work or how inexpensive (ready to race at about $30,000 – 1980 pricing), they’re going to like its style.

“We worked very hard on that,” says Kirby. Both he and Steffan are serious about the aesthetics, and neither one had to convince the other that looks were near the top of the priority list. Judge for yourself from the photographs, but I think they succeeded.

Originally published in Canadian Yachting’s October 1980 issue.

Specifications:

LOA – 29ft 10in

LWL – 24ft 6in

Beam – 10ft 2in

Draft – 5ft

Displacement – 5,500lbs

Ballast – 2,350lbs

Sail Area – 435 sq ft

IOR – 29.5ft

Phrf avge – 137

Photo Captions:

Photo 1 – Profile

Photo 2 – Builder Dick Steffan has equipped the K30 with the kind of fittings you’d expect on a well tuned one design.

Photo 3 – The nav table gets priority while the rest of the interior is sparse.Photo 4 – Big main and small chute are easily handled in a blow

Photo 4 – Once you’ve sailed a three-quarter rig anything else is just plain boring.

Photo 5 – Under Sail.

Photo 6 – Layout.

Photo 7 – Bruce Kirby developed his lines without resorting to the bumps and hallows typical of an IOR design. Designer and builder agreed that performance alone wouldn’t sell – the boat also had to look fast. Deck space is flat and unobstructed.