Ask Andrew: Steering system maintenance

Apr 22, 2021

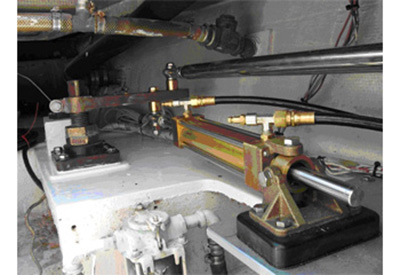

A hydraulic steering ram, at the rudder. This ram is designed to control two rudders simultaneously

An important, but often overlooked maintenance item on any type of boat is it’s steering system. Most are relatively safe and secure, and are generally bulletproof – requiring very little maintenance to operate well. That said, it’s important to perform at minimum an annual inspection before launch to avoid looming failures and potentially costly repairs.

There are three main types of steering systems found on boats, with a range of hybrid options:

Hydraulic steering

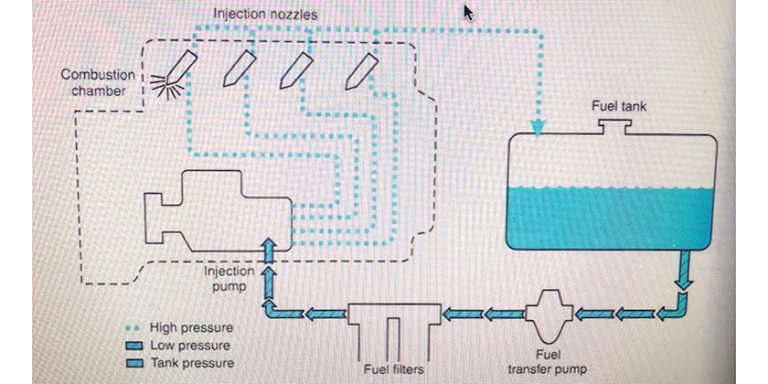

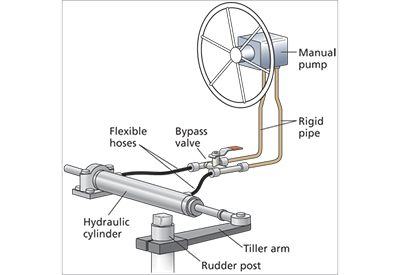

A hydraulic steering set-up

A hydraulic steering set-up

This system uses two reservoirs (one at the helm and one at the rudder) and pressurized hydraulic lines (filled with oil) to convert steering wheel turns to movements of a hydraulic steering ram.

The system should be checked for leaks throughout, paying particular attention to the seals on the ram and helm unit. Make sure any flexible hoses are in good shape with no dry rot or cracking. Check all fittings and connections on all the tubing for leaks as well. Most systems will use metal tubing as this does not flex, giving the system a spongy feel. Follow the tubing throughout its run, carefully checking for corrosion or damage. Pay particular attention to where tubing passes through bulkheads, as these are areas where chafe and corrosion often occur. If the system is pressurized and has a reservoir, check the fluid level and pressure levels. Spin the wheel hard over and count the turns and note any noise while doing this. If it is noisy or there are an excessive number of turns, there may be air in the system.

Oil leaks are the main cause of problems on hydraulic systems. Small leaks can be handled by regularly topping off the reservoir until repairs can be made. However, if any air gets into the system it will cause the steering to feel spongy or even fail altogether. To test for air, put the wheel hard over in both directions. If it bounces back when released, that’s a pretty good indication of trapped air.

Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for bleeding air from the system. It often involves filling the reservoirs, using tubing, closing any cylinder bypass lines, turning the wheel to bleed air from the cylinder bleed screw and repeating the process, as some air may migrate up through the system to the top reservoir.

An engine-mounted power-steering pump, driven by the engine’s serpentine belt

An engine-mounted power-steering pump, driven by the engine’s serpentine belt

Hydraulic systems on small powerboats can utilize a power steering pump mounted on the engine. The turning engine turns a belt that activates the power steering pump. Filled with fluid, the pump allows the hydraulic system to work. If engine squeals or tough steering are noted, check the engine mounted pump for low fluid, leaks or a broken belt.

Mechanical Steering

Mechanical steering systems, also known as manual or non-power steering, or push-pull systems.

There are a number of different set-ups – but two main types are divided into power and sail:

The view beneath the pedestal on a sailboat, showing how the cables move from the pedestal, aft to the rudder

The view beneath the pedestal on a sailboat, showing how the cables move from the pedestal, aft to the rudder

Sailboats will often have a wheel mounted on a pedestal within the vessel’s cockpit. Inside the pedestal will be a gear (or series of gears) that controls a chain or wire through a 90-degree pulley system. The upper leg of the system runs vertically in the pedestal, and lower leg runs fore/aft from the pedestal to the rudderstock. A set-up with bearings and stops will surround the rudderstock and will allow adjustments to be made to the cables that control the wheel-to-rudder movement. Stops, wire and bearings should also be inspected.

On powerboats, mechanical steering uses push-pull cables which connect the steering wheel and helm at the front of the boat with the outboard motor. This system provides good handling performance and safe operation for smaller powerboats.

Housed behind the instrument panel and wheel at the helm, the rack-and-pinion set-up converts the steering wheel movements into the push-pull action on the cable. The helm has a round gear that holds the turning cable. Different helms cause a different number of lock-to-lock steering wheel turns (the number of times it takes get a fully-turned wheel on one side fully turned to the other side). More wheel turns means less effort to turn the boat.

The push-pull cable that moves the rudder or engine in response to the steering wheel being turned is called simply the steering cable. The motor-end of the steering cable fits within a tilt-tube, and allows for inspection, greasing, and disassembly for repair and replacement.

If repairs are needed in a mechanical steering system, start at the steering arm (at the motor):

a) Disconnect the steering arm from the cable’s motor/rudder end and turn the steering wheel. If the cable now moves freely, you have an issue with the motor, stern drive unit, or rudder.

If the cable does not move at all, but the steering wheel freely moves, then the problem is most likely at the helm.

Next, look at the rudder, stern-drive or outboard: Each should be inspected and greased at least annually to prevent issues.

Find the grease fitting and add a little grease to see if this will fix it. Be careful not to add too much, or you can blow out the seals, depending on the type.

If adding grease doesn’t fix the issue, it is time for the boat to come out of the water for inspection and repair. If you are on the water, it is time to call for help.

Finally, check for problems in the tilt-tube:

Start by unscrewing the nut that connects the outer sleeve to the tilt tube and carefully remove the cable end in its metal sleeve (if possible). If this proves difficult, or the cable end isn’t moving, the cable between the rack and the motor may need to be replaced.

3) Tiller steering

In this set-up, a tiller handle is attached directly to a rudder, allowing the skipper in the cockpit to manually swing the rudder beneath the waterline.

Keeping the steering ‘tight’, meaning that there is little excess movement, and the rudder engages as the tiller arm is moved is important. It’s important to monitor the bushings/bearings and pintles, to ensure that they are in serviceable condition.

Tillers can be made of solid wood, laminated wood, composite or metal (or a combination). If laminated, check for any delamination and weakening. If built of more than one piece, check the fittings and connections to ensure that they are solid.

The rudder should also be considered – If made of fibreglass or wood, water intrusion into the core is always a potential worry. If water enters into the rudder, the internal stainless steel parts might begin to corrode, leading to failure in such a way that the blade pivots on the stock independent of the tiller. Grounding, and underwater damage can also shock and damage the bearing that surrounds the rudderstock. Check the bearing for damage, wear and lubrication as required.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.