Ask Andrew: Safe Starts

Aug 8, 2019

Ensure battery cables, and heavy gauge, high-current-carrying cables are secured tightly. This picture shows a cable running to an engine’s starter motor

On the Friday before a weekend with a gorgeous forecast, I heard on the news that a boat had exploded at a local marina; the boat’s operator was seriously injured. At the time, I heard that authorities were investigating and were attempting to determine the cause of the explosion and fire.

What would I do if an explosion occurs on a boat that I was working on? What was the cause? How could this happen?

In the single update to the news story, authorities blamed ‘User Error’ after refueling, as one possibility for the accident – which is a scary thought. In the process of searching the internet, I found some interesting results via Google. Try ‘Boat Explosion’ or ‘Boat Fire’ – for even more terrifying stories and images.

How do we, as boaters, stay safe on the water?

As a marine mechanic, I watch boaters regularly start, run, shut-down, refuel and dock their boats – and many of us do the small things that keep us safe by rote. Things like ‘Run blower for 5 minutes before starting engine’…and ‘all persons, except for the gas attendant, shall be onshore during refueling’…….but do we understand why these rules keep us safe? Let’s examine these more closely.

I would guess that the most dangerous boating operations are during engine/electrical start-up, and during refueling. These are the times that the perfect storm of elements is in play to create an explosion: Gasoline vapors and spark. When gasoline is at relatively low temperatures, the liquid changes to a gas – and in this state it is highly volatile – a spark is enough to cause ignition/explosion.

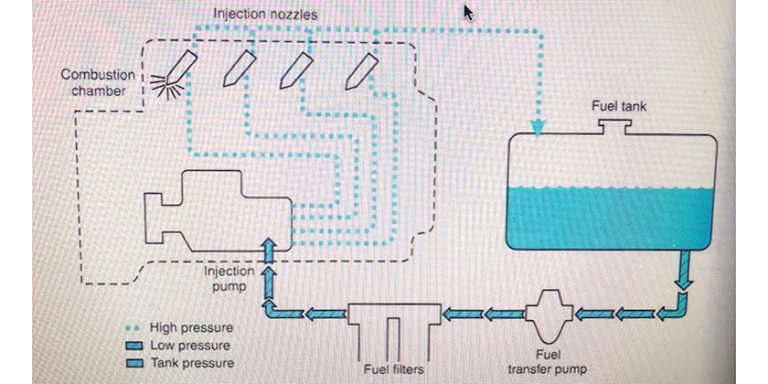

In a typical marine engine – fuel is stored in a fuel tank: which could be a red remote tank, or a plastic, steel or aluminum internal tank. Tanks of all types need to be vented to allow fuel to flow in and out of the tank. The lines to fill the tank, and run from the tank to the engine are typically rubber, and are secured by steel hose clamps. Fuel is pumped into the carburetor (which is vented), where engine combustion occurs. In addition, the engine compartment is filled with electrical wiring and components: batteries, blowers, lights, chargers, alternators, starting motors, distributors, spark plug leads, ignition coils, ground posts, bus bars, trim motors, solenoids (the list goes on and on). As you can imagine, vapours are present constantly, and so is the potential for an electrical spark. A damaged or poorly maintained engine can easily become a bomb.

So – how do you make sure your boat is safe?

During the course of my work, I am constantly testing and starting up engines in boats that I’m unfamiliar with – I don’t know what work has been done in the past, or what condition the engine and electrical is in, at present. So, to protect myself as I look over a boat, and begin planning to start it up, I follow this checklist:

1) Open the engine hatch and keep it open during the entire start-up/warm-up procedure. This allow me to vent the engine compartment, allows me to have fresh air inside if I need to get a better look, lets me see the state of the engine and electrical systems, and lets me do further checks.

A typical blower installation: note that the lower hose runs below the engine to pick op gasoline fumes, and the upper hose runs to a vent. Note also the electrical connections, appropriately crimped, and secured.

A typical blower installation: note that the lower hose runs below the engine to pick op gasoline fumes, and the upper hose runs to a vent. Note also the electrical connections, appropriately crimped, and secured.

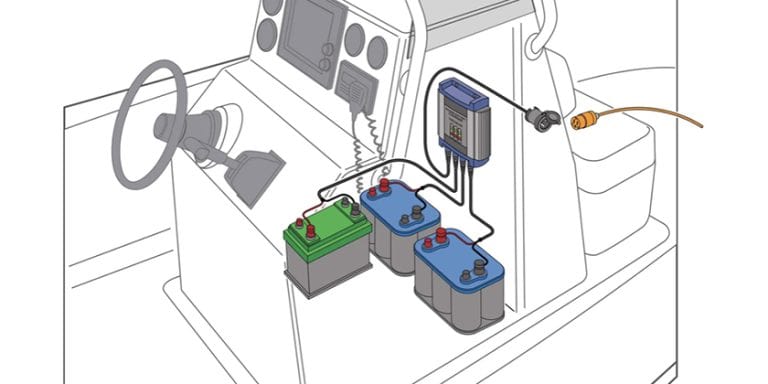

2) Most people turn the blower on first. That’s what the sticker says, right? ‘Run blower for 5 minutes before starting engine’. But: What if there are vapours in the engine room? And what if the blower motor or wiring is compromised and a spark is created, by turning the blower fan on? Before turning anything electrical on, I do a thorough check of the electrical in the engine compartment: Are battery terminals tight (with a wrench, not by hand)? Is any wiring exposed? Do all electrical components have tightly secured terminals (including starters, solenoids, blowers, battery chargers, etc)? While looking for tight connections, look at the state of wiring (corrosion and exposed ends). (Also a great time to check engine oil, power steering fluid, belts, hoses, etc)

A quick note about non-marine parts: I’ve heard many people say that the word ‘Marine’ on a box doubles the price. It’s a running joke (and sometimes true), but part of the reason that ‘marine rated’ parts should be used is due to the ‘ignition protected’ nature of marine components. ‘Ignition Protected’ indicates that the component cannot create an external spark – it is protected from creating a spark that could cause an explosion. Napa and Canadian Tire sell engine ignition coils that will work just fine on your Mercury inboard – except they likely wont be ignition protected, which means they would have the potential to case a spark, igniting gasoline vapours

3) Once you’ve confirmed that connections are tight and secure, and that ignition protected components are used, power can be turned on: Battery switches turned on, blowers are engaged, bilge pumps tested, ignition keys turned to engage power and gauges, etc.

A note on blowers: Blowers have two hoses – one end run to the base of the engine, the other secured to a vent to push vapours overboard into the open air. Gasoline vapours are denser than air and will collect at the lowest point of the engine room (below the engine itself). If blower hoses are damaged or re-directed, they wont perform their intended purpose of venting vapours overboard.

The sticker on a marine engine’s starter motor indicates that this starter is ‘ignition protected’ and is safe to use in marine applications.

The sticker on a marine engine’s starter motor indicates that this starter is ‘ignition protected’ and is safe to use in marine applications.

4) Once fumes/vapours are blown out of the engine compartment, the engine can be started. The key you turn at the helm engages an electrical device that draws power from the batteries to the starter motor. A lot of power. Because of this, this is the point that the greatest amount of spark is possible in any loose/damaged connections.

5) With the engine running, visually check the engine. Check for any leaks (water or fuel). Allow it to run long enough to get up to regular operating temperature. Once you’ve confirmed that the engine is running as it should, you can close the engine hatch and prepare to depart.

Refueling operations are another dangerous time to consider – again, the perfect storm of vapours and electricity are present.

Before refueling, always turn off all electrical equipment (every switch on the helm, every switch on the electrical panel, the main battery switch, and the ignition key). This will prevent any accidental spark will gasoline vapours are present.

During refueling, the fuel attendant will pump gas into a tank, which is vented (sometimes through a separate vent, other times through a vent in the gasoline fill. Spills are possible. Vapours are present. Overfilling and spilling is a danger.

The additional danger when refueling is the potential for spark through static electricity (through people moving on and off the boat and building up static, as well as the potential between different metals found between the fuel nozzle, the fuel fill, and anything else electrically connected or bonded to them. Modern boats will have each separate metallic component grounded/bonded to reduce the possibility of static electricity buildup – but these connections need to be checked and repaired as necessary to prevent the possibility of creating a spark. Older boats may not have grounding or bonding system in place at all, so extra care should be taken when refueling.

Before starting up after refueling, run blowers with the engine hatch open. If a remote tank is used, try to keep it in a well-ventilated area, away from any electrical components.

Boats with diesel engines have their own set of safety precautions that I hope to address in a future article – they are no more or less inherently safe, just have their own foibles.

I hope this article serves to keep us all safe – it’s scary to think of all that can go wrong when trying to enjoy a great summer activity. A few precautions, and understanding the ‘why’ and ‘how’ will allow us to comfortably enjoy this great pastime. Enjoy!

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.