The Middens of Galiano Island

Layers of history, crowds of tourists

By Catherine Dook

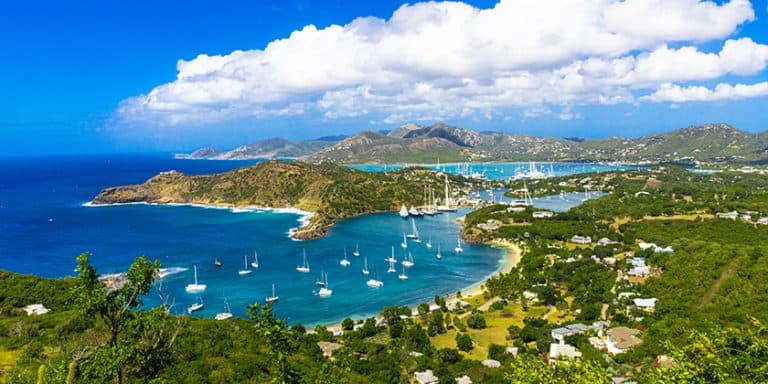

We motored our way into Montague Harbour along a twisted channel with our engine muffled by the leaning trees.

“This is peaceful,” I told my husband, John.

“Look,” I pointed to an eagle sitting on the top of a tree overlooking the channel entrance like a sentinel giving permission for us to pass. Dignified, unruffled, his impassioned gaze noted and then dismissed us, as uninteresting and perhaps unworthy. I was tired. We’d pulled up anchor at Portland Island that morning, and the grind of the diesel engine had worn me down.

Galiano Island was given its name 150 years ago by the English Navy in honour of a Spanish navigator they respected, Captain Richarde Galiano. Japanese settlers in the late 1800s made charcoal pits like those of Wakayamo, Prefecture, Japan, which archaeologists have found on the south end of the island.

But three thousand years ago, the Hul’qumi’num-speaking people pulled their 20-metre ocean-going canoes along this same channel with their paddles dipping in quiet accord, their arm and back muscles flexing, their bodies weary from the journey. Their last stop may have been Saltspring Island. Their canoes were crowded with families and supplies – fishhooks, some woven cedar cooking baskets, live coals wrapped in leaves, digging tools, sand bows and arrows, and some dried food for the journey. Choosing their tides, they could travel five or six knots. The Hul’qumi’num owned many canoes, some of them small for river use. A canoe was not just utilitarian, but an object of beauty and pride. Each canoe was carved out of a single cedar log. The carver placed coals down the length of the log, then chipped out the resulting charcoal with bone or stone tools. He carved the prow with designs that identified his family, and then painted it with berry juice, animal blood, and charcoal. Then the canoe was named – Seal or Salmon or Thunderbird. The symbolism carved into its bow connected the First Nations owner to the physical and spirit worlds. As he and his family paddled into Montague Harbour, sitting in the graceful craft he’d carved with his own hands, they must have felt at one with their world.

No one knows how many families summered on Galiano Island, digging for mollusks, fishing for crabs and hunting birds and small mammals. The First Nations paddled south from Penelekut Island every year to Galiano to harvest clams.

Many Elders of the Penelekut Island Hul’qumi’num First Nations say they began with an ancestor named Stutsun who was one of twelve people who fell from the sky. Stutsun fell onto the mountain overlooking the Chemainus River Delta. Others emerged from the earth, but the first people taught their children the potlatch and how to encounter the spirits that live in fresh water. The Hul’qumi’num people prowled lightly on the face of the world from Penelekut Islsand to the Fraser River on their seasonal food-foraging routes, trading with neighbours and visiting with kinship groups as they travelled.

Many Elders of the Penelekut Island Hul’qumi’num First Nations say they began with an ancestor named Stutsun who was one of twelve people who fell from the sky. Stutsun fell onto the mountain overlooking the Chemainus River Delta. Others emerged from the earth, but the first people taught their children the potlatch and how to encounter the spirits that live in fresh water. The Hul’qumi’num people prowled lightly on the face of the world from Penelekut Islsand to the Fraser River on their seasonal food-foraging routes, trading with neighbours and visiting with kinship groups as they travelled.

Because they intended to return to their seasonal camps many times over their lifetime, they left them much as they’d found them. Their bark cooking-vessels are gone, and their pole and vegetation summer dwellings have rotted away. All that is left of our early First Nations on Galiano Island are middens and a legend or two, as well as descendants who still respect the old ways. Nobody knows what our early First Nations thought and how their rituals, songs, and art reflected their view of the world. Even today, the big house ceremonies are too sacred to reveal to outsiders. We do know that, based on caste, some people who died were laid out in wooden boxes and placed in trees, and others were buried in middens. An anthropologist would call middens trash heaps, but our British Columbia First Nations say they are burial sites. ’q’unup they are called in Hul’qumi’num, which means ‘white ground.’

And they are very beautiful. They are white shell beaches, some of which extend metres down, and they are thousands of years old. Think of it. For time immeasurable before our baby country was hatched from its colonial egg, the Hul’qumi’num people visited these sites on a yearly rhythm and they placed the shells of the mollusks they harvested in the same place, until there was a heap that changed the landscape. There is a simplicity to that; a deliberate predictability that could teach important lessons to our present clamouring world.

There is a legend from Galiano Island, collected by the eminent anthropologist Franz Boas in the 1880s. It is said that the island started as a tree with branches that reached the sky, and people as well as deer with white backs and black legs descended the tree. Then the story shifts with a dreamlike twist that makes no sense to non-First Nations. The people decided to bring down the tree [the hwunitum (white man – the hungry people) clamours to know why, but the story sweeps on without explanation. Is the ambiguity of the plot a metaphor for the unpredictability of life? Does it train the listener to a mindset of accepting the unknowable?]. Two men asked some rats to gnaw through the tree. It took many rats 20 days to get to the middle of the tree, whereupon the men asked the rats to commence on the other side. As the rats gnawed, the people sang to make themselves brave. The tree fell and the top broke off and formed a small island nearby; many deer then lived on the islands.

We are not even sure this story comes from Galiano, though Boas thought it did. In common with other legends of the Coast Salish, it tells us that the first people descended from the sky, that natural objects transform to other natural objects (the tree changes into an island), that there was an easy communication between man and animals, and that man could influence his environment – in this case by commanding the rats. The story ends with plentiful food for the Hul’qumi’num people. To this day, our First Nations are permitted to gather food on Galiano Island, as they have for thousands of years.

John prowled the anchorage looking for a good spot, then we anchored. After we’d rested, we motored our Zodiac to the marina park.

There are two middens in the provincial campground there, one at Montague Harbour and the other half a kilometre west at the end of a winding footpath that the park authority put in place just last year. I was anxious to see both.

The midden on the harbour is the built-up bank overlooking the beach. The thick line of white shells on the upper level of the beach shows where the water of the ocean has eroded the midden.

I stood on the bank, fully eight feet above the water, and thought on how this bit of ground, covered with gnarled trees and grasses and a marking sign, was a sacred place. I thought how our First Nations had lived and feasted there over so many thousands of years and I could hardly wrap my mind around the concept.

Then I followed the trail west to the other midden.

“Best not to try this path wearing bifocals,” I thought, as it was a very twisted and uneven way indeed, but at the other end was a p’q’unup (‘white ground’), of very great beauty, and a score of visitors in bathing suits, and as I found out later at low tide, a million bivalves squirting up through the foreshore mud. Seagulls strutted among them looking for dinner.

“Best not to try this path wearing bifocals,” I thought, as it was a very twisted and uneven way indeed, but at the other end was a p’q’unup (‘white ground’), of very great beauty, and a score of visitors in bathing suits, and as I found out later at low tide, a million bivalves squirting up through the foreshore mud. Seagulls strutted among them looking for dinner.

It was the day of the partial eclipse of the sun of 2017.

I stood up to my ankles in seawater as the sun dimmed, and asked my husband to take a picture.

It seemed fitting that at the time of a great phenomenon of nature, I should stand on an ancient place. It seemed respectful, and wonderful.

As our First Nations embraced nature, so nature embraces us.

Sources:

Muckle, Robert J. “The First Nations of British Columbia, an Anthropological Overview” 3rd ed. 2014, UBC Press

Franz Boas, a translation, 1895, “Indian Myths and Legends from the North Pacific Coast of America,” Talonbooks, 2002

Arnett, Chris, “The Terror of the Coast, Talonbooks, 1999