Surge Narrows: Part three in CYOB West’s survey of the major routes north of Desolation Sound

Nov 22, 2018

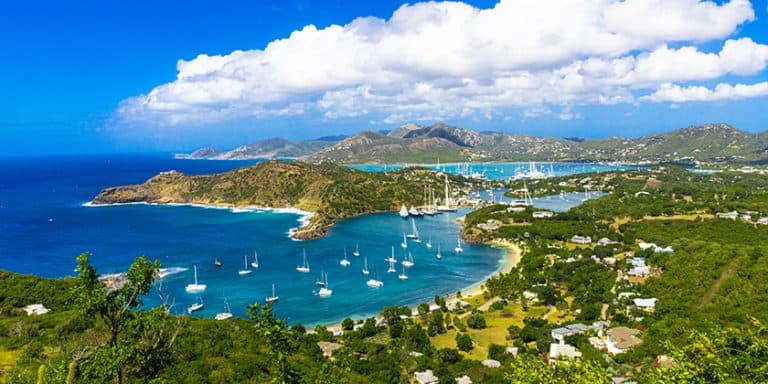

In many ways, the middle route (Surge Narrows to the Okisollo Rapids) is more interesting if you plan to continue on to Johnstone Strait. This route connects almost directly with the strait and its rapids are not as intimidating as the Dents because they have slightly less current over a shorter distance with less turbulence. This route is a good introduction to the northern passes and offers the added bonus of superb scenery and excellent anchorages. The first rapids lie at Surge Narrows; some six miles north are the more turbulent Okisollo Rapids.

Whirlpools and eddies spin off Jimmy Judd Island in Gillard Pass during a strong flood

Surge Narrows, also known as Beazley Passage, is the fastest-flowing pass of the middle route and currents here can be turbulent, especially on the south-setting flood. Fortunately there is only one stream.

This passage actually begins at Welsford Island at the southeast end and extends northwest through Beazley Passage, where the current is strongest, and on to Surge Narrows, between Antonio Point and Quadra Island. Beazley Passage is the only safe channel through the Settlers Group of islands but it does present certain difficulties on both flood and ebb.

On the flood there is a strong deflection off the southwest part of Sturt Island. This generates tremendous turbulence in the shear zone that crosses the pass. Working the back eddy off Sturt Island and crossing the shear zone (as we once vainly attempted) is not an option because it is too easy to lose control in this turbulent area and, because the pass is narrow, you have little room to recover.

The ebb produces less turbulence, but there is the hazard of Tusko Rock, which dries at low water and is located just west of Sturt Island in line with the ebb set from the pass. Boaters should favour the west side of the passage until well clear of Peck Island.

Passing to the west of Peck Island is not recommended because of strong turbulence. The route north of Sturt Island is not recommended either because of its numerous rocks and reefs, and strong, turbulent currents that can set you into danger quickly.

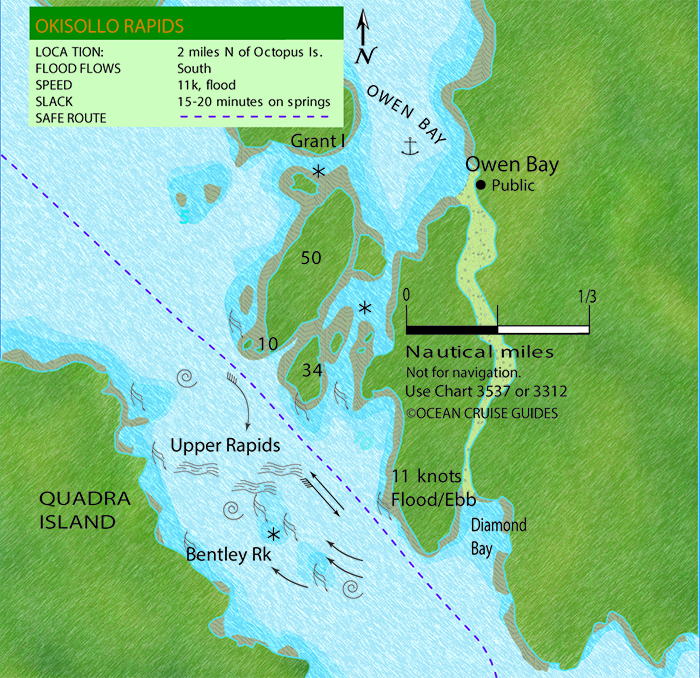

If you bypass Octopus Islands Marine Park, you’ll be heading straight into the Okisollo Rapids. Currents in the Upper Rapids, the first set of rapids encountered when northbound, are considerably stronger (up to 11 knots) than those in the Lower Rapids, which usually run less than six knots. The Upper Rapids are also encumbered with reefs and rock outcroppings that generate strong deflections. The area near Bentley Rock can be quite turbulent on large tides.

On the south-flowing flood, the strongest deflection is just south of two small islets (one of which is marked “10” on Chart 3537) on the east side of the channel below Owen Bay. The safest route through this pass favours the east side of the channel, giving Bentley Rock a wide berth. During floods it is safe to cross over to Quadra Island once you are past Diamond Bay.

The ebb in the Upper Rapids is even more confused, especially downstream of Bentley Rock. Avoid the strong set to Bentley Rock by crossing to the east side of the channel well upstream. Currents in Okisollo Channel are strongest around this rock and the forces of water here are very hazardous.

Although the Upper Rapids can be turbulent, the pass is fairly wide and there are opportunities to pull out and assess the situation if conditions are uncomfortable. Owen Bay is a good anchorage to wait out strong tides.

The Lower Rapids are more benign, with currents rarely exceeding five knots in the channel south of Gypsy Shoal. The channel north of Okis Islands is free of hazards with less current.

Once free of the “Oaks” you can make your way around Chatham Point to the eastern entrance of Johnstone Strait – and all the joys which lie ahead.

There’s something exciting about a voyage along Discovery Passage. Hemmed in by the steep slopes of Vancouver Island and the forested shores of Quadra Island, this wide ribbon of cold, swift-flowing water bustles with commercial traffic all summer long.

Discovery Passage was once plied by native peoples in dugout canoes; it was not until the Klondike Gold Rush in 1898 that steamships started pushing north along this major stage of the Inside Passage. Cruise ships have replaced steamships but the flow of traffic here remains under the control of the great gatekeeper, Seymour Narrows. Even leviathan liners are careful to time their transits for slack water at this pass, one of the most formidable on our coast.

For the northbound boater, this passage can be a very easy transit. It really starts a few miles south of Cape Mudge, where the first effects of currents from Johnstone Strait are felt north of Mitlenatch Island. Even in calm conditions, the waters here can be choppy and rolling. In strong southerly winds (25 knots or more) against a flood stream, the seas can be truly dangerous and over the years many vessels have been lost here, usually during winter storms. In summer, southeasterlies are not as common but seas can still be rough and currents strong in the area three or four miles south of Wilby Shoals.

If you’re bucking a flood tide, the best way to avoid current is to pass close by the red buoy at Wilby Shoals (stand off a mile to avoid the set) and follow the 20-metre line to Cape Mudge lighthouse. This will keep you away from the rough water coming out of Discovery Passage and inside the back eddy that starts south of Cape Mudge. Once past the lighthouse, follow the Quadra Island shoreline until you’re near Whiskey Point, then either cross over to Campbell River or stay along the Quadra shore to the anchorage of your choice.

The charts provided for in this article are meant to give the reader an overview of the area and should not be used for navigational purposes.

By William Kelly

Photos and maps by Ocean Cruise Guides