Hopetown and the Other Loyalists

The first thing I see on my approach to Hopetown is an undulating emerald silhouette rising up from the horizon, dominated by a circa-1864, candy-cane-painted lighthouse that still uses kerosene for power.

The first thing I see on my approach to Hopetown is an undulating emerald silhouette rising up from the horizon, dominated by a circa-1864, candy-cane-painted lighthouse that still uses kerosene for power.

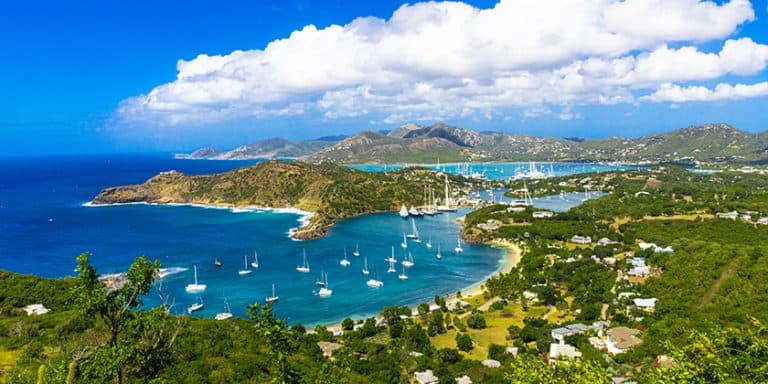

Inside the harbour is a forest of sailboat masts. A chorus of dancing casuarinas trees, feathery branches seductive as a burlesque dancer’s boa, serenades me.

And then I see the village – a sort of psychedelic Nantucket.

Think New England with pastel colours. Clapboard houses and shops capped by dormered roofs and gables. Some roofs have a Norman influence – steeply pitched and curved like you’d see in rural Quebec. But there’s no snow here.

We’re in the Sea of Abaco in the northern Bahamas, a shallow sea that stretches roughly two hundred kilometers along the Bahama Bank. The waters outside Hopetown are neon lime and incandescent turquoise, testament to the fact that depths here are never more than twenty feet. They make for gorgeous if unnerving sailing. In his book, Sailing Away From Winter, Silver Donald Cameron called sailing here “champagne cruising.”

The Abacos boast two actual islands, eighty two cays and two hundred and eight rocks.

And Hopetown.

In his definitive cruising guide to the Abacos, Steve Dodge writes that “Hopetown is clearly one of the most picturesque settlements in the Bahamas.” That’s partly due to the striking geography: lush vegetation towers over a town that strolls up a gentle dune to the east, fronting on a pink coral beach decorated by sea oats and bay lavender. It’s partly due to the architecture, the result of a fascinating history close to my own heart.

On a visit to the United Loyalist Cemetery in St. John, New Brunswick, I long ago discovered my own pedigree. My Loyalist ancestors helped settle Canada. But a whole lot of other Loyalists – the ones I now envy – came to Hopetown.

The Wiannie Malone Historical Museum, housed in an imposing white clapboard house with green trim, vividly outlines Hopetown’s early history. Curator Linda Cole explains that Wiannie Malone was a Loyalist from South Carolina who was forced to move from the United States in the aftermath of the American Revolution. “According to all of our records Malone was one of the first settlers here, arriving around 1784,” says Cole. “Hopetown was a staunch Loyalist colony. Even its name attests to this history. The earliest visitors disembarked from a brigantine named ‘Hope’.”

As I later stroll along the two village streets – Front Street and the King’s Highway – I reflect on my own history and wonder what my life would be like if my forebears headed south.

On my first reconnaissance mission I also note that Hopetown is oriented first and foremost to the water. Cap’n Jack’s, a rambling white clapboard structure with bubblegum pink trim, perches on stilts above the water, boasting its own dinghy docks. All wood inside and sporting a multitude of nautical bric-a-brac, it is a meeting place for visiting cruisers and the more lubberly types who usually come for long stays and are, for the most part, repeat offenders. “I’ve been here twenty times,” says Oakville resident Ally Munro. “And I’m going to keep coming back.”

The health clinic is a coral-painted building right beside a police station that scowls down on Front Street like a colonial great house, painted powder blue with white trim. Behind the police station stands a Methodist Church that bursts, at noon, into a carillon concert of hymns. The melodies mesh with the grumble of outboard motors on the dinghies that criss-cross the bay, with the wind that rustles the palm fronds overhead, with the murmur of the surf just past the dunes.

But it’s the people that are Hopetown’s biggest draw. “The policeman is the DJ too,” says Munro. Graham Lavender of the Abaco Journal likes the fact that “there are no strangers here.” According to Peggy Thompson, who runs Hopetown Hideaways, an eclectic collection of inns and villas, “the proprietor of Vernon’s grocery, who’s famous for his pies and breads, is also the lay minister at the Methodist church.”

The accommodations we discover at Hopetown Hideaways add to a feeling that, for all its raucous colour, for all its semi-tropical ambiance, this place still feels like home. Our digs at Hideaway Villas sport a private pool ten feet from a row of docks, a huge deck with its own barbecue, gardens and groves where we can harvest fresh limes for our drinks, mangos and bananas for our breakfast, avocados for lunch, and a twelve-foot fiberglass launch for our exclusive use.

Early in the morning on New Year’s Day, I am sitting on the deck of Hopetown Coffee Shop, meditating over a homemade chicken curry quiche that I wash down with a coffee made from beans that are roasted on site.

The street below meanders along the shore of the harbour on its morning constitutional. Just around the corner neat white picket fences worthy of Cape Cop border colonial homes and shops. But these buildings boast pink and lemon, turquoise and lavender with aquamarine trim. Blossoming bougainvilleas decorate these gardens. Palms and casuarinas stand in for oaks and maples.

This village may share its history with Upper Canada but I find myself wishing, as the breezes riffle the harbour waters, sending sailboat masts swaying before the candycane lighthouse backdrop, that I was descended instead from those other Loyalists.

Then I could claim, as my birthright, a storybook village called Hopetown.