Discovery Channel: Part 4 and the final segment of CYOB’s series on the passages north of Desolation Sound

Nov 22, 2018

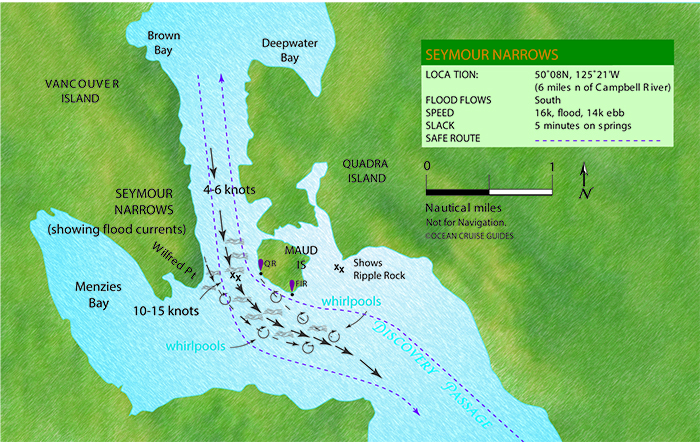

Discovery Channel, between Campbell River and Quadra Island, is a busy place so, in addition to constant current, be prepared for traffic. There are the hourly crossings of the Quadra Island car ferry, the comings and goings of tugs (often with booms or barges), fishboats, numerous pleasure craft and the cruise ships, which usually transit the pass during evening or nighttime slack. On weekends there can be three or four cruise ships lined up from Seymour Narrows to Campbell River. However, Discovery Passage is fairly wide and straight, and you can easily pick a clear spot if you need to cross the channel. Keep your VHF on Channel 16 if you need to clarify a situation with another vessel. The cruise ships respond quickly.

Large commercial ships always arrive at Seymour Narrows at slack. If it is sunny, also bet on a northwest wind.

Seymour Narrows

In the 1950s, the currents of Seymour Narrows were measured using drift poles (eight-foot-long two-by-two’s with lead at either end and a flag stick) and a transit mounted on a cairn on Maud Island. Surveyors would measure the time the pole needed to travel at given angles on the transit to determine current speed. Canadian Hydrographic Service staff eventually used a 25-foot inflatable dinghy with plenty of horsepower to stay in one position in the pass while a probe, three feet below the surface, measured current.

Hydrographers say the strongest currents in Seymour Narrows are near Ripple Rock, slightly west of mid-channel, directly beneath the hydro lines between Vancouver and Maud islands. On a flood, the strongest turbulence will be along the west wall and in the area south of Ripple Rock. On an ebb, the turbulence – and the set – starts between Maud Island and Ripple Rock. The current sets northwest to the west wall.

Northbound vessels should arrive off the Maud Island light within an hour of the ebb finishing or beginning. However, if it is a neap tide and traffic is light, it is safe to transit the Narrows at any time during the ebb.

In the narrows, steer toward the tongue of the current stream (east of mid-channel) to avoid the whirlpools and eddies north of Maud Island up to North Bluff. On big tides in low-powered vessels it’s prudent to be at the Maud Island light at slack or just a few minutes into the north-flowing ebb. If the slack is low water, be sure to arrive at the pass before the end of the ebb because slack here on large tides is not long – five to 10 minutes at most – and you’ll want to be past Brown Bay before the south-flowing flood gets under way, which can challenge a slow boat. On a large flood, Seymour Narrows can reach 16 knots – no place to be in any kind of boat.

Southbound boats should be opposite Brown Bay within an hour of a spring flood ending or beginning. If a large spring flood is under way, it may be wise to be here within a half-hour of its end or beginning. Keep away from the west shore when transiting the narrows. The worst turbulence is often south of Ripple Rock, especially if wind is against current. If you stay on the starboard side of the channel throughout the transit, you’ll be out of harm’s way in the event you are sharing the narrows with a boom-towing tug or large ship. The good news about Seymour Narrows is that there are no obstructions and just one strong, main stream.

When reading current tables, boaters often assume that the speed of the ebb or flood builds slowly and consistently to maximum flow – and being one hour late for slack means the current should be only a fraction of the maximum flow. However, there are surges and slow periods of flow as water backed up at one end of the pass is suddenly released at slack and rushes through to temporarily equalize with the water level on the other side. The flow in Seymour Narrows is non-linear – in other words, the current can come on strong very quickly.

The main thing to keep in mind, especially in a slow-moving boat, is not to try bucking the tide at the narrows – a hazardous practice at this pass. If you try to use the Maud Island back eddy, which reaches about three knots in a northerly direction, and your boat has a hull speed of 10 knots you are travelling at 13 knots over the ground. When your boat crosses over the flooding jet – which it has to do right near the beacon – it could be hit with 15 knots of current. Suddenly the hull is forced to go at almost 30 knots through the water for a brief time and the bow wave can go over the prow or perhaps cause the vessel to roll. You also run the risk of overheating your engine, which could happen just as a large tug and barge are approaching. Be safe – go with the current just before or after the turn.

The charts provided for in this article are meant to give the reader an overview of the area and should not be used for navigational purposes.

By William Kelly

Photos and maps by Ocean Cruise Guides