BC Tidal Passes: Passes Beyond Desolation Sound

By William Kelly

Photos and maps by Ocean Cruise Guides

This month, we survey the major routes north of Desolation Sound, where some of BC’s best cruising grounds lie just beyond a series of challenging tidal passes.

This month, we survey the major routes north of Desolation Sound, where some of BC’s best cruising grounds lie just beyond a series of challenging tidal passes.

Beyond Desolation Sound lies a beckoning labyrinth of forested islands, inlets and anchorages guarded by a number of tidal passes adjacent to Vancouver Island. Because of the strength and speed of the currents in these passes, boaters may be apprehensive about attempting the transit to the greener pastures ahead. But taking an informed and calculated risk at these gateways leads you on to greater rewards in cruising grounds and anchorages to the north.

Currents flood south in the passes leading to Johnstone Strait and Cordero Channel so cruisers need to catch ebbs to go north and floods to return home in the south.

The main commercial route is Discovery Passage, which starts opposite Cape Mudge and continues for more than 20 miles to Chatham Point. The main pass here is the infamous Seymour Narrows where currents can reach 16 knots on ebb. This is an excellent route and our favourite because it takes us quickly to Johnstone Strait once we come up the west side of the Strait of Georgia.

However, many northbound boaters choose the “back route” around the top of Sonora Island via Cordero Channel. This route – through the Yuculta Rapids, Gillard Passage and the Dent Rapids – is the most direct route north from Desolation Sound.

However, many northbound boaters choose the “back route” around the top of Sonora Island via Cordero Channel. This route – through the Yuculta Rapids, Gillard Passage and the Dent Rapids – is the most direct route north from Desolation Sound.

The other popular option for northbound boaters is the “middle route” between Quadra and Sonora islands, through Surge Narrows (or Whiterock Passage and Hole in the Wall) and the Upper and Lower Rapids in Okisollo Channel. This route offers the opportunity to stop at Octopus Islands Marine Park, where a cluster of islets provides a beautiful and sheltered anchorage that accommodates many vessels.

The middle route is the easiest for boaters new to these northern passes. Although Surge Narrows and Okisollo Channel can run fast, they have less turbulence and present a shorter section of strong current than the long stretches from Yuculta Rapids to the Dents or along Discovery Passage to Seymour Narrows.

Yuculta and Dent Rapids

The series of passes from the Yucultas (pronounced “uke-la-taws”) to the end of the Dents stretches over four miles but transit for most boats should take only 30 to 45 minutes. If you are northbound to the Yucultas, try to arrive just as the flood is turning to slack – this will enable you to ride the ebb by the time you reach Gillard Passage.

The series of passes from the Yucultas (pronounced “uke-la-taws”) to the end of the Dents stretches over four miles but transit for most boats should take only 30 to 45 minutes. If you are northbound to the Yucultas, try to arrive just as the flood is turning to slack – this will enable you to ride the ebb by the time you reach Gillard Passage.

The predominant characteristic of these rapids is the choppy water and turbulence that start south of Kellsey Point on Stuart Island and continue to Gillard Passage. This channel is deep and fairly wide, with the least turbulence in mid-channel right up to Whirlpool Point.

Slower vessels arriving at the end of a flood can take advantage of a back eddy along the Stuart Island shore up to Kellsey Point. From there, if conditions are safe, cross to the Sonora Island side of the channel (where the north-going ebb current begins early) and continue to Gillard Passage.

The Yuculta Rapids are a sort of catch basin for debris flowing from the other passes. Some pieces of wood may be submerged below the top layer of fresh water that flows from Bute Inlet. Debris not buoyant enough to be supported by this freshwater layer can sink to the denser saltwater three to six feet down, so keep a sharp eye for deadheads and other wood bobbing just below the surface.

Strong currents really get under way in the area opposite Whirlpool Point (or Outhouse Point, as locals call it). Three streams converge on the flood to make the area opposite Big Bay one of the most turbulent and confused pieces of water anywhere on the BC coast. Combined with a mix of fresh water from mainland rivers and streams, especially in late spring, these currents and overfalls are impressive.

Because the water also turns 90 degrees between Yuculta Rapids and Gillard Passage, large whirlpools and holes form east of Gillard Island during flood conditions. The area southeast of this island is especially dangerous during large flood tides, as is the area between Jimmy Judd and Gillard Islands. The flood set is very pronounced onto the west end of Jimmy Judd, and this area between the two islands is also where the current will be strongest.

Because the water also turns 90 degrees between Yuculta Rapids and Gillard Passage, large whirlpools and holes form east of Gillard Island during flood conditions. The area southeast of this island is especially dangerous during large flood tides, as is the area between Jimmy Judd and Gillard Islands. The flood set is very pronounced onto the west end of Jimmy Judd, and this area between the two islands is also where the current will be strongest.

We usually like to be in Gillard Pass at the onset of the ebb but if you find yourself still battling a lot of flood current, an alternate route north is to proceed across the mouth of Big Bay and navigate east of the 15.8-metre sounding in Barber Passage, which runs slightly slower than Gillard Passage.

Proceeding north from Jimmy Judd Island, arrive with Little Dent Island to starboard and the ebb under way. On a strong flood, Devils Hole, a turbulent and aerated section of water south of Little Dent Island, can be a frightening spot, but on an ebb the stream is much more consistent because there is nothing to deflect the flowing water. If you find yourself riding a faster ebb than you have planned, stay in the middle of the pass to avoid the set to Tugboat Passage with its dangerous rocks.

Once you are clear of the Dent Rapids – that is, west of Little Dent – steer north of the shoal patch marked as 6.4 metres depth about a half-mile northwest of the QR light on Little Dent. There can be lots of turbulence here on an ebb.

Once you are clear of the Dent Rapids – that is, west of Little Dent – steer north of the shoal patch marked as 6.4 metres depth about a half-mile northwest of the QR light on Little Dent. There can be lots of turbulence here on an ebb.

Transiting the Dents southbound is usually an easier proposition; they turn to flood 15 to 25 minutes before Gillard Passage, enabling you to ride the early flood south. Devils Hole should not present difficulties for most powered boats early in a flood.

The main difficulties at the Dents occur during strong floods as a result of the tremendous wrenching Little Dent Island gives the tidal stream at the northwest tip of the island. This forces a major deflection of current over to the Sonora Island shore which in a large tide gives tardy southbound boaters (such as ourselves on one occasion) the appearance of the edge of a waterfall as it actually drops onto the back eddy east of the QR light. If you are going with the flood, favour the Sonora Island shore until you are well past Dent Island.

The area around the Yucultas and the Dents offers numerous spots to wait for the next slack or spend the night. They include Big Bay public dock on Stuart Island, the Dent Island Lodge Resort on the small islands east of Dent Island (a reservation for overnight moorage is recommended) or the anchorage in Mermaid Bay.

Surge Narrows

In many ways, the middle route (Surge Narrows to the Okisollo Rapids) is more interesting if you plan to continue on to Johnstone Strait. This route connects almost directly with the strait and its rapids are not as intimidating as the Dents because they have slightly less current over a shorter distance with less turbulence. This route is a good introduction to the northern passes and offers the added bonus of superb scenery and excellent anchorages. The first rapids lie at Surge Narrows; some six miles north are the more turbulent Okisollo Rapids.

Surge Narrows, also known as Beazley Passage, is the fastest-flowing pass of the middle route and currents here can be turbulent, especially on the south-setting flood. Fortunately there is only one stream.

This passage actually begins at Welsford Island at the southeast end and extends northwest through Beazley Passage, where the current is strongest, and on to Surge Narrows, between Antonio Point and Quadra Island. Beazley Passage is the only safe channel through the Settlers Group of islands but it does present certain difficulties on both flood and ebb.

On the flood there is a strong deflection off the southwest part of Sturt Island. This generates tremendous turbulence in the shear zone that crosses the pass. Working the back eddy off Sturt Island and crossing the shear zone (as we once vainly attempted) is not an option because it is too easy to lose control in this turbulent area and, because the pass is narrow, you have little room to recover.

The ebb produces less turbulence, but there is the hazard of Tusko Rock, which dries at low water and is located just west of Sturt Island in line with the ebb set from the pass. Boaters should favour the west side of the passage until well clear of Peck Island.

Passing to the west of Peck Island is not recommended because of strong turbulence. The route north of Sturt Island is not recommended either because of its numerous rocks and reefs, and strong, turbulent currents that can set you into danger quickly.

Okisollo Channel (Upper and Lower Rapids)

If you bypass Octopus Islands Marine Park, you’ll be heading straight into the Okisollo Rapids. Currents in the Upper Rapids, the first set of rapids encountered when northbound, are considerably stronger (up to 11 knots) than those in the Lower Rapids, which usually run less than six knots. The Upper Rapids are also encumbered with reefs and rock outcroppings that generate strong deflections. The area near Bentley Rock can be quite turbulent on large tides.

If you bypass Octopus Islands Marine Park, you’ll be heading straight into the Okisollo Rapids. Currents in the Upper Rapids, the first set of rapids encountered when northbound, are considerably stronger (up to 11 knots) than those in the Lower Rapids, which usually run less than six knots. The Upper Rapids are also encumbered with reefs and rock outcroppings that generate strong deflections. The area near Bentley Rock can be quite turbulent on large tides.

On the south-flowing flood, the strongest deflection is just south of two small islets (one of which is marked “10” on Chart 3537) on the east side of the channel below Owen Bay. The safest route through this pass favours the east side of the channel, giving Bentley Rock a wide berth. During floods it is safe to cross over to Quadra Island once you are past Diamond Bay.

The ebb in the Upper Rapids is even more confused, especially downstream of Bentley Rock. Avoid the strong set to Bentley Rock by crossing to the east side of the channel well upstream. Currents in Okisollo Channel are strongest around this rock and the forces of water here are very hazardous.

Although the Upper Rapids can be turbulent, the pass is fairly wide and there are opportunities to pull out and assess the situation if conditions are uncomfortable. Owen Bay is a good anchorage to wait out strong tides.

The Lower Rapids are more benign, with currents rarely exceeding five knots in the channel south of Gypsy Shoal. The channel north of Okis Islands is free of hazards with less current.

The Lower Rapids are more benign, with currents rarely exceeding five knots in the channel south of Gypsy Shoal. The channel north of Okis Islands is free of hazards with less current.

Once free of the “Oaks” you can make your way around Chatham Point to the eastern entrance of Johnstone Strait – and all the joys which lie ahead.

Discovery Passage and Seymour Narrows

There’s something exciting about a voyage along Discovery Passage. Hemmed in by the steep slopes of Vancouver Island and the forested shores of Quadra Island, this wide ribbon of cold, swift-flowing water bustles with commercial traffic all summer long.

Discovery Passage was once plied by native peoples in dugout canoes; it was not until the Klondike Gold Rush in 1898 that steamships started pushing north along this major stage of the Inside Passage. Cruise ships have replaced steamships but the flow of traffic here remains under the control of the great gatekeeper, Seymour Narrows. Even leviathan liners are careful to time their transits for slack water at this pass, one of the most formidable on our coast.

For the northbound boater, this passage can be a very easy transit. It really starts a few miles south of Cape Mudge, where the first effects of currents from Johnstone Strait are felt north of Mitlenatch Island. Even in calm conditions, the waters here can be choppy and rolling. In strong southerly winds (25 knots or more) against a flood stream, the seas can be truly dangerous and over the years many vessels have been lost here, usually during winter storms. In summer, southeasterlies are not as common but seas can still be rough and currents strong in the area three or four miles south of Wilby Shoals.

If you’re bucking a flood tide, the best way to avoid current is to pass close by the red buoy at Wilby Shoals (stand off a mile to avoid the set) and follow the 20-metre line to Cape Mudge lighthouse. This will keep you away from the rough water coming out of Discovery Passage and inside the back eddy that starts south of Cape Mudge. Once past the lighthouse, follow the Quadra Island shoreline until you’re near Whiskey Point, then either cross over to Campbell River or stay along the Quadra shore to the anchorage of your choice.

Discovery Channel, between Campbell River and Quadra Island, is a busy place so, in addition to constant current, be prepared for traffic. There are the hourly crossings of the Quadra Island car ferry, the comings and goings of tugs (often with booms or barges), fishboats, numerous pleasure craft and the cruise ships, which usually transit the pass during evening or nighttime slack. On weekends there can be three or four cruise ships lined up from Seymour Narrows to Campbell River. However, Discovery Passage is fairly wide and straight, and you can easily pick a clear spot if you need to cross the channel. Keep your VHF on Channel 16 if you need to clarify a situation with another vessel. The cruise ships respond quickly.

Seymour Narrows

In the 1950s, the currents of Seymour Narrows were measured using drift poles (eight-foot-long two-by-two’s with lead at either end and a flag stick) and a transit mounted on a cairn on Maud Island. Surveyors would measure the time the pole needed to travel at given angles on the transit to determine current speed. Canadian Hydrographic Service staff eventually used a 25-foot inflatable dinghy with plenty of horsepower to stay in one position in the pass while a probe, three feet below the surface, measured current.

In the 1950s, the currents of Seymour Narrows were measured using drift poles (eight-foot-long two-by-two’s with lead at either end and a flag stick) and a transit mounted on a cairn on Maud Island. Surveyors would measure the time the pole needed to travel at given angles on the transit to determine current speed. Canadian Hydrographic Service staff eventually used a 25-foot inflatable dinghy with plenty of horsepower to stay in one position in the pass while a probe, three feet below the surface, measured current.

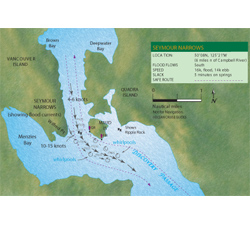

Hydrographers say the strongest currents in Seymour Narrows are near Ripple Rock, slightly west of mid-channel, directly beneath the hydro lines between Vancouver and Maud islands. On a flood, the strongest turbulence will be along the west wall and in the area south of Ripple Rock. On an ebb, the turbulence – and the set – starts between Maud Island and Ripple Rock. The current sets northwest to the west wall.

Northbound vessels should arrive off the Maud Island light within an hour of the ebb finishing or beginning. However, if it is a neap tide and traffic is light, it is safe to transit the Narrows at any time during the ebb.

In the narrows, steer toward the tongue of the current stream (east of mid-channel) to avoid the whirlpools and eddies north of Maud Island up to North Bluff. On big tides in low-powered vessels it’s prudent to be at the Maud Island light at slack or just a few minutes into the north-flowing ebb. If the slack is low water, be sure to arrive at the pass before the end of the ebb because slack here on large tides is not long – five to 10 minutes at most – and you’ll want to be past Brown Bay before the south-flowing flood gets under way, which can challenge a slow boat. On a large flood, Seymour Narrows can reach 16 knots – no place to be in any kind of boat.

Southbound boats should be opposite Brown Bay within an hour of a spring flood ending or beginning. If a large spring flood is under way, it may be wise to be here within a half-hour of its end or beginning. Keep away from the west shore when transiting the narrows. The worst turbulence is often south of Ripple Rock, especially if wind is against current. If you stay on the starboard side of the channel throughout the transit, you’ll be out of harm’s way in the event you are sharing the narrows with a boom-towing tug or large ship. The good news about Seymour Narrows is that there are no obstructions and just one strong, main stream.

Southbound boats should be opposite Brown Bay within an hour of a spring flood ending or beginning. If a large spring flood is under way, it may be wise to be here within a half-hour of its end or beginning. Keep away from the west shore when transiting the narrows. The worst turbulence is often south of Ripple Rock, especially if wind is against current. If you stay on the starboard side of the channel throughout the transit, you’ll be out of harm’s way in the event you are sharing the narrows with a boom-towing tug or large ship. The good news about Seymour Narrows is that there are no obstructions and just one strong, main stream.

When reading current tables, boaters often assume that the speed of the ebb or flood builds slowly and consistently to maximum flow – and being one hour late for slack means the current should be only a fraction of the maximum flow. However, there are surges and slow periods of flow as water backed up at one end of the pass is suddenly released at slack and rushes through to temporarily equalize with the water level on the other side. The flow in Seymour Narrows is non-linear – in other words, the current can come on strong very quickly.

The main thing to keep in mind, especially in a slow-moving boat, is not to try bucking the tide at the narrows – a hazardous practice at this pass. If you try to use the Maud Island back eddy, which reaches about three knots in a northerly direction, and your boat has a hull speed of 10 knots you are travelling at 13 knots over the ground. When your boat crosses over the flooding jet – which it has to do right near the beacon – it could be hit with 15 knots of current. Suddenly the hull is forced to go at almost 30 knots through the water for a brief time and the bow wave can go over the prow or perhaps cause the vessel to roll. You also run the risk of overheating your engine, which could happen just as a large tug and barge are approaching. Be safe – go with the current just before or after the turn.

Anne Vipond and William Kelly are authors of the popular Best Anchorages of the Inside Passage distributed in BC by Heritage House.

Photo Captions:

Photo 1 – Approaching Gillard Pass northbound. There can be leftover turbulence here at the tail end of a flood.

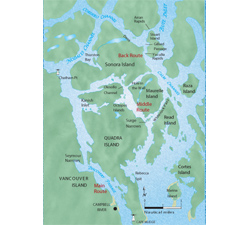

Photo 2 – Overview map of the area.

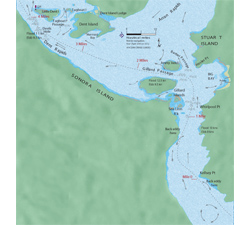

Photo 3 – Map of the Dent Rapids.

Photo 4 – The power and fury of Dent Rapids: the flood current is wrenched by Little Dent Island and creates dangerous whirlpools and overfalls.

Photo 5 – Upper Okisollo Rapids can be hazardous near Bennett Rock.

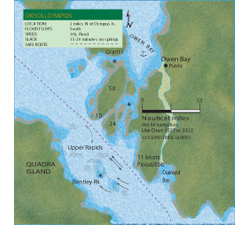

Photo 6 – Map of the Okisollo Rapids.

Photo 7 – Whirlpools and eddies spin off Jimmy Judd Island in Gillard Pass during a strong flood.

Photo 8 – Map of the Seymour Narrows.

Photo 9 – Large commercial ships always arrive at Seymour Narrows at slack. If it is sunny, also bet on a northwest wind.