Fusion 15

By Doug Hunter

By Doug Hunter

I have been watching the Fusion 15 one-design dinghy evolve for several years now, as it progressed from preliminary drawings on the Canadian yacht designer Steve Killing, to a production model with twenty-nine boats sold and counting. Along the way, I’ve also had the chance to sail both a prototype and the final production model. It’s been an interesting process and additionally rewarding to see a new design succeed, in terms of both the criteria pursued by the purpose-built company, Fusion Sailboats of Woodview, Ontario and the positive reception garnered from the marketplace.

The history of the boat biz is aggressively littered with great concepts that failed -or proved, even in the radiance of their genius, not to have a practical market, either because of some idiosyncrasy of the design or, more often, the designer or the builder’s failure to understand the marketplace.

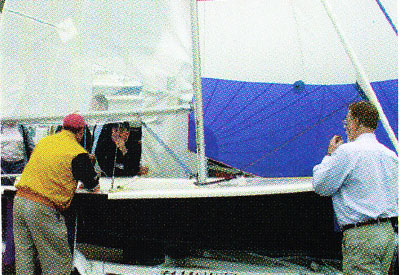

So why has the Fusion thus far succeeded? How was Fusion Sailboats able to sell eight of these things at the 2001 Toronto International Boat Show without even having to provide the prospective buyers with a test sail? That achievement alone amazes me, since sailors are central casting’s very definition of tire kickers. The simple answer is that Fusion has managed to come up with a design so self-evidently appealing that people have consistently demonstrated an impressive willingness to buy one based on sight alone. And we’re talking about $9,900, which gives you a boat complete with mainsail and selftacking jib.

So why has the Fusion thus far succeeded? How was Fusion Sailboats able to sell eight of these things at the 2001 Toronto International Boat Show without even having to provide the prospective buyers with a test sail? That achievement alone amazes me, since sailors are central casting’s very definition of tire kickers. The simple answer is that Fusion has managed to come up with a design so self-evidently appealing that people have consistently demonstrated an impressive willingness to buy one based on sight alone. And we’re talking about $9,900, which gives you a boat complete with mainsail and selftacking jib.

But it didn’t become so alluring by jumping straight out of Killing’s brain and into the production shop. The Fusion 15 changed significantly as it moved from the drawing board through several prototypes to a final production model. It has plainly succeeded because there was a commitment on the part of the designer and builder to tinker and fiddle, but mainly to adapt the basic design to address an evolving, multilevel market.

The process began on the one hand with a designer who had crossed to the wiser side of fifty and had been doodling a “what-if” dinghy that wouldn’t punish an old guy’s knees in the pursuit of recreational racing. On the other hand, there was a design client, Tim Sherin, who was looking for something less cramped and wet than a Laser II that he could sail with his wife. Andre Calla, a RCYC member who knew both Sherin and Killing, put the former in touch with the latter in 1999. They found a common desire, says Killing, to create a boat that “filled the gap between the current flock of high performance athletic tip-over-at-the-dock dinghies” (e.g., 49er or a double-trapezing 14) “and the daysailers we grew up with” (e.g., Albacore).

The process began on the one hand with a designer who had crossed to the wiser side of fifty and had been doodling a “what-if” dinghy that wouldn’t punish an old guy’s knees in the pursuit of recreational racing. On the other hand, there was a design client, Tim Sherin, who was looking for something less cramped and wet than a Laser II that he could sail with his wife. Andre Calla, a RCYC member who knew both Sherin and Killing, put the former in touch with the latter in 1999. They found a common desire, says Killing, to create a boat that “filled the gap between the current flock of high performance athletic tip-over-at-the-dock dinghies” (e.g., 49er or a double-trapezing 14) “and the daysailers we grew up with” (e.g., Albacore).

The result was the basic Fusion design, which I think of as a twenty-first century Albacore. Faster and more nimble to be sure, but like an Albacore without a spinnaker. Not for long, though. “People wanted a spinnaker for excitement,” Killing says, and I thoroughly agree. I grew up racing Lightnings and the idea of racing off the wind without something colourful and balloon-like to fool with is anathema. “l have to admit now it was a good decision,” Killing says. And so, after an initial prototype was put through its paces in 2000, a different Fusion emerged in 2001, as three fiberglass prototypes hit the water with an asymmetrical chute.

A clipper-style reverse curve was given to the bow’s profile to move the tack of the chute sufficiently ahead of the jib to give the sail breathing room. Killing wanted to avoid a retractable bowsprit altogether because it is mechanically complicated and invites serious damage to the hull in a collision.

The spinnaker system works beautifully, with a halyard and a retrieval line making hoists and douses very clean with the chute passing into and out of its stowage area by slipping under a curved aluminum bar at the bow. And the jib rolls neatly away on its furler, making hoists and drops a snap. While the spinnaker system is priced as an option, I can’t imagine playing with this boat without it. There’s just too much fun involved.

The spinnaker system works beautifully, with a halyard and a retrieval line making hoists and douses very clean with the chute passing into and out of its stowage area by slipping under a curved aluminum bar at the bow. And the jib rolls neatly away on its furler, making hoists and drops a snap. While the spinnaker system is priced as an option, I can’t imagine playing with this boat without it. There’s just too much fun involved.

On the other hand, the trapeze is definitely an option. “A lot of husband and wife teams didn’t want it, but the kids did,” Killing explains. In fact, the enthusiasm of the younger crowd for the prototype design was a pleasant surprise. “Very selfishly, I designed this boat for me and fortunately there’s a whole lot of people like me around. It was conceived for couples and older folks, not kids. But when they saw the prototype, they got excited, and now the youth market is now significant for the boat.”

To keep the kids amused, the trapeze option was added to prototype testing in 2001, with the result that the initial rig was stiffened to accommodate it. But class rules don’t permit its use during racing. The boat is sufficiently stable that parking your backside on the hiking-friendly deck is usually enough to keep the boat on its feet, and hiking, when necessary, is not of the brutal, hamstrings-pressed-to-the-topsides variety.

Fundamentally, this is a very easy boat to sail. Easy, however, without being dull. The big difference between racing a Fusion and one of the higher performance, double handed dinghies is that with the Fusion, you can easily get your head out of the boat to pay attention to wind shifts and tactics. You aren’t consumed with acrobatics and intricate boat speed tweaking as you’re trying to keep track of oscillations on the opening beat. The self-tacking jib allows a skipper to take along a novice and have every confidence of getting around the racecourse safely. The asymmetrical chute is simple to manage and so also lends itself well to excursions with neophytes. The more experienced crew can spend upwind legs reading the compass, keeping track of shifts and competitors, and then be rewarded with some kite flying off the wind-a very nice package of performance and inclusiveness.

The Fusion is sufficiently sprightly to please most any experienced sailor who isn’t hooked on pure adrenal thrills. I actually liked the slightly damped-down sensation when I sailed it one particular night with Killing while the true wind was crossing Midland Bay at 15 knots plus. The boat had good momentum, I wasn’t getting particularly soaked while hiking, and the boat’s groove seemed forgivingly wide as we chugged ably to windward. (A 505 or 470 would have been screeching to windward on a plane, but I would have had to be out on a trapeze in a drysuit.) Off the wind, the chute popped the boat onto an energetic plane and I was still happily parked on my butt on the deck. In targeting the gymnastically reluctant recreational sailor who still wants the hands-on fun of a dinghy, the Fusion delivers as promised.

The reason the Fusion doesn’t buck and lunge like a high-performance dinghy is because it doesn’t have the shallow hull form otherwise encountered in a cookie baking sheet. Fusion Sailboats has been able to build a robust, long lasting hull that doesn’t cost as much or is as prone to flexing as a vacuum-bagged taco shell. If you’re looking for a longterm investment, that’s important. Bang for your buck is further ensured through the use of top-quality Harken hardware and Quantum sails.

The reason the Fusion doesn’t buck and lunge like a high-performance dinghy is because it doesn’t have the shallow hull form otherwise encountered in a cookie baking sheet. Fusion Sailboats has been able to build a robust, long lasting hull that doesn’t cost as much or is as prone to flexing as a vacuum-bagged taco shell. If you’re looking for a longterm investment, that’s important. Bang for your buck is further ensured through the use of top-quality Harken hardware and Quantum sails.

For Fusion, there are four basic markets. Club racing is now in place at six Ontario sailing clubs. Within this club racing subset is what Killing calls “old guy racing.” There’s the cottage market, which has come through with orders, and finally, what may prove to be the most critical market, junior sailing. In part because of the lure of this market, Fusion will build the boat with a conventional symmetrical spinnaker and pole as well as a jib with standard sheeting.

The Ontario Sailing Association negotiated the use of two of the first hulls for its instructor certification clinics. Program director Alex Albertson issued a high-five assessment of the boat. “It represents a fun, fast racing machine, and also a platform on which novice sailors can improve their skills.” “Who should sail the Fusion?” he proposed. “Well, anyone who is interested in having a great sail in a boat that is deceptively quick for its 290 pounds.”

Amen.

A former editor of Canadian Yachting, Douglas Hunter is the author of twelve books, including Yacht Design Explained (W.W. Norton) with Steve Killing.

Originally published in Canadian Yachting’s January 2003 issue.