Boston Whaler 11 w/ Volvo 90

By Andy Adams

Powerboat yachtsmen and cruising sailors both use tenders. Boston Whaler is the worldwide, hands down favourite, and since Volvo seems very keen on the Canadian outboard market, I paired the 11-ft.-4-in. Boston Whaler and the Volvo 90 outboard.

It was an arranged marriage and I was delighted it worked as well as it did. In fact, the Volvo’s ideal application is on the transom of a slow, heavy sailboat. It’s a high-torque auxiliary not designed for a light, fast planing boat. More on that later…

Actually Volvo simply handed a new engine over and said, ” Keep it till it’s run in, then do your test.” Boston Whaler (actually Chuck Brown at Sea Mark Industries) dropped the Whaler off and never had a chance to retrieve it. I had the whole rig for much of last summer, and had a terrific time with it.

Where the Whaler excels is in demanding heavy-use situations. If you only use a small fishing boat for one trip yearly and could just as easily get by with a canoe, then the Whaler is pure overkill. But if you have several small children using a boat every day of the summer, or have a power cruiser or a very large sailing yacht and need a combination tender and emergency boat that just can’t let you down, the Whaler is the best choice.

“Unsinkable” says it all. The hull and interior liner are bonded to be one piece and are pressure -foam filled from bow to transom. This results in a boat that can be, as the early Whaler ads showed, cut in half and floated away. Even filled to the gunwales with water and carrying a full load, the Whaler will float and stay upright. For life-boat use that feature could be worth any price. Equally true for children’s use.

Another interesting thing about Whalers is their longevity. You will seldom meet a Whaler owner that needed to replace his first Whaler except to move up. Yacht clubs, water taxis and other institutional uses are where the Whaler really pays for itself, but to capitalize on that sort of thing, each Whaler comes with a transferrable 10-year hull warranty against structural defects.

There’s not the space here to list all the warranty points but you’d better believe that Boston Whaler stands behind their product. The construction techniques used are one reason they can offer that warranty but there is more than that. The boats are uncommonly light and easy to carry.

There’s not the space here to list all the warranty points but you’d better believe that Boston Whaler stands behind their product. The construction techniques used are one reason they can offer that warranty but there is more than that. The boats are uncommonly light and easy to carry.

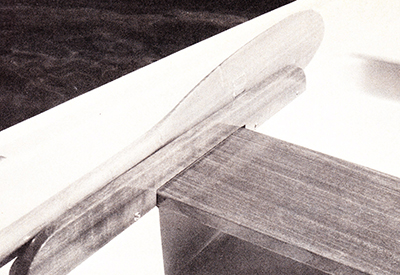

Good design really comes into focus when you pick this little boat up. The gunwales are shaped to fit your hand and there are no sharp edges. Except at the transom the whole boat is surrounded by a perfect hand-hold. A big rubber trim-strip covers the outside edge to finish it.

Some varnished trim accents the interior and gives it a nautical look. There are side panels that hold oars or paddles (and two sets of sturdy oar locks), a wooden centre seat and two wooden hatch-covers. The remainder of the seating is fibreglass, all self-draining and equipped with good quality plugs.

In use the Whaler tracks in a solid sure-footed way, stays flat even when used as a swim platform, and is low enough in the gunwales for easy fishing. You could use the storage areas as live wells.

It should be no surprise that whaler quality doesn’t come cheap. But, at $2,240 it isn’t out of line after all we’re not comparing it to an aluminum car topper-this is a thoroughly-engineered, carefully built boat even if it is small.

But, I called this an arranged marriage. The problem was that to give the 8.5-hp Volvo its best chance I should have had it on a sailboat. Volvo lists it as a sail motor meaning it performs best as an auxiliary. Hanging it on the back of the Whaler may not have been fair. The Whaler planes easily and moves fast. The high-torque Volvo motor just wasn’t ever intended to scoot along at 26-30 mph. The little motor ran out of prop at about 12 mph, so it was out of its element.

Pulling the cord on the Volvo is easy, and brings the engine to life on the second try almost every time. Strangely, it started best while dead cold and gave the most trouble when fully warmed up. The difficulty here could have been caused by one of the least satisfactory aspects of the design: the fuel-line coupling comprising a nipple on the engine and a female plug on the line.

Where the Volvo differs from the practice followed by Mercury is that the engine nipple has no ball-stopper. When disconnected, the Mere coupling seals itself in both sections so there’s no leaking. The Volvo line coupling seals, but the nipple on the engine does not, requiring the operator to push the hanging rubber cap over the end. This is provided by the factory, but it is a very awkward way of keeping the fuel in the engine.

Where the Volvo differs from the practice followed by Mercury is that the engine nipple has no ball-stopper. When disconnected, the Mere coupling seals itself in both sections so there’s no leaking. The Volvo line coupling seals, but the nipple on the engine does not, requiring the operator to push the hanging rubber cap over the end. This is provided by the factory, but it is a very awkward way of keeping the fuel in the engine.

The first problem is that one sometimes forgets the cover plug, leaving fuel all over the engine bilge. The next is that when you do remember, the plug will develop suction making it difficult to remove. Also, when the engine is left connected, the fuel seems to drain through the engine. This explains why it starts with a squeeze of the fuel-line ball and a bit of choke, but not with just a pull of the cord.

When was the last time you used an engine with 360° rotations for reverse? The Volvo has it, plus a regular reverse gear too. The little load prop that is supplied as standard has almost as much torque in reverse as forward anyway, but that extra boost of 360° reversing could be the difference between missing and hitting the pier.

Gear-changing itself is simple and seems quite positive with no grunching noises or reluctance. The folding arm throttle control is similarly familiar with a very long travel in the twist grip. It is easy to get the Volvo to run at exactly the right speed.

A lift bar at the front of the engine is well-balanced for carrying the engine, but it isn’t the lightest engine, nor is it compact. Volvo also has a series of four-stroke engines much more in line with the design practices of Mere and OMC. The test engine was two-stroke and, of course, required the usual 50:1 gas/oil mix.

In use the Volvo ran well and was stingy with fuel. After a whole month of regular use, and despite the fuel line hassle, there was still gas in the tank. That’s a nice plus on any boat but it’s particularly important if the motor is being used as a sail auxiliary where it’s going to be dragged out of a locker and told to take the boat home on a half a tank.

Knowing the whaler’s ability to float full of water and the Volvo’s high-torque power, I filled the boat then planed it off with ease. No problem for boat or motor.

I mentioned earlier that a fisherman could use the storage areas as live-wells but in fact, you could fill the whole boat. Imagine the looks you’d get at the campsite with a boat full of live fish, maybe a couple of 20-lb bass swimming around in there. Actually the Whaler/Volvo combination might be a pretty good idea after all…

Originally published in Canadian Yachting’s May 1979 issue.

Specifications:

Length – 11ft 4in

Beam – 5ft

Weight – 210 lbs

Engine – Volvo 90 hp8.5

Fuel Capacity – 11 litres

Photo Captions:

Photo 1 – Good design comes into focus every time you operate or handle this boat.

Photo 2 – Seats and panels weather well and double as oar racks.

Photo 3 – The Volvo has 360° reverse pivot.