Exploring Fish Egg Inlet

Story & Photos by William Kelly and Anne Vipond

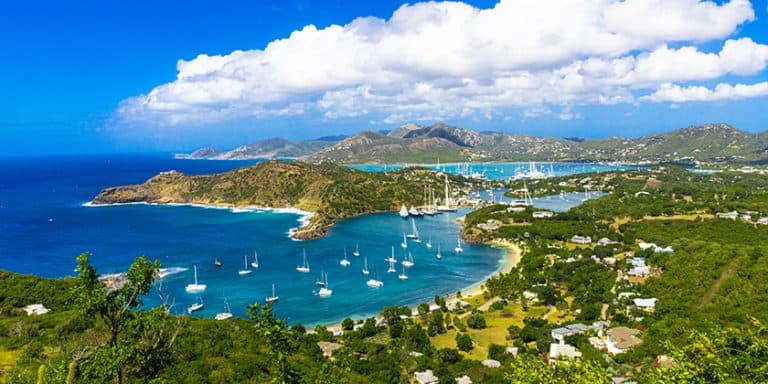

Just off Fitz Hugh Sound, Fish Egg Inlet boasts a maze of islets and a multitude of anchorages, all waiting to be discovered.

Of all the boating we’ve done along the Inside Passage, one of our favourite cruising areas lies just north of Cape Caution. Once past this aptly named cape, we usually make a beeline up Fitz Hugh Sound to revisit anchorages we first pulled into 20 years ago. Many of the wilderness anchorages along BC’s central coast change little from year to year. It’s the people visiting them who change. In our case, we were no longer cruising in our 35′ liveaboard sailboat with about as much freedom as we’ll ever have. Now we have business commitments, a house and kids, but life is good and we were boating with our boys. Plus, we had a new sailboat – a 48-footer – which seemed just the right size for two adults, two teenagers and one small dog.

It felt exhilarating to be on a month-long summer trip, and even better to be sailing past Cape Caution just one week after setting out in early July from our marina on the Fraser River near Vancouver. Our reward for rounding Cape Caution was the welcoming sight of Fitz Hugh Sound. This broad, 40-mile-long channel is lined with mainland mountains and scenic inlets that we planned to explore. But first we promised John, our 14-year-old, that we would try to catch a salmon. After all, we were in sportfishing heaven and it was time to slow down and put a line in the water.

It felt exhilarating to be on a month-long summer trip, and even better to be sailing past Cape Caution just one week after setting out in early July from our marina on the Fraser River near Vancouver. Our reward for rounding Cape Caution was the welcoming sight of Fitz Hugh Sound. This broad, 40-mile-long channel is lined with mainland mountains and scenic inlets that we planned to explore. But first we promised John, our 14-year-old, that we would try to catch a salmon. After all, we were in sportfishing heaven and it was time to slow down and put a line in the water.

Large runs of salmon enter Fitz Hugh Sound through Hakai Passage on their way to spawn in mainland rivers, so the odds were in our favour. But we had no luck fishing from our dinghy just outside our Fury Island anchorage at the mouth of Rivers Inlet. We did, however, see humpback whales feeding on the far side of the sound near Cape Calvert.

The next morning, while trolling for a salmon, we saw more humpback whales as we motored up the sound toward Fish Egg Inlet. One was feeding right outside the entrance to this inlet. We were so distracted watching the humpbacks diving and breaching that the sound of a salmon hitting the line startled us. Bill reeled it in with John’s help and we had a beautiful chinook to barbecue for dinner.

The next morning, while trolling for a salmon, we saw more humpback whales as we motored up the sound toward Fish Egg Inlet. One was feeding right outside the entrance to this inlet. We were so distracted watching the humpbacks diving and breaching that the sound of a salmon hitting the line startled us. Bill reeled it in with John’s help and we had a beautiful chinook to barbecue for dinner.

Entering Fish Egg

We put our catch on ice and turned our attention to piloting our vessel into Fish Egg Inlet. Addenbroke Island, its lighthouse overlooking Fitz Hugh Sound, is one of several islands lying at the entrance to Fish Egg Inlet. Addenbroke’s 100-year-old lighthouse is perched on a cliff and is an obvious landmark. In 1928 the lighthouse was the scene of a grisly murder when the keeper was found dead of a gunshot wound. A hermit living in a tent at Safety Cove was the prime suspect but just as police were closing in for the capture, he vanished and was never found.

Entry from the south is through Convoy Passage into the central part of Fish Egg Inlet, which branches into numerous bays and unnamed coves. The inlet wasn’t surveyed until 1984 and remained undiscovered by most boaters until a CHS chart (Chart 3921) was published in the early ’90s. Until then, navigating around the vast array of islands and small inlets within Fish Egg Inlet called for local knowledge. Fish Egg Inlet is over seven miles long and four miles wide; within its scenic shores are several, perhaps dozens, of secluded and snug anchorages.

Fish Egg Inlet is a rockfish conservation area where no lines are allowed in the water, but recreational boaters can still set their crab and prawn traps. One note of caution: because charting of this area is relatively recent, it’s wise to take your time in shallow areas and always watch the depth sounder. There have been a few reports of uncharted rocks. The entire inlet is fairly protected in all but the most insistent breezes and it’s a pleasure just to motor about to the various anchorages.

We headed to Joe’s Bay for the night. This snug anchorage lies midway along the north side of Fish Egg Inlet and includes a dramatic set of reversing falls. We prefer to anchor in the deep part of the cove in about 60′ and usually have the place to ourselves. If it’s busy, we take a line to the south shore. The drying rock opposite the island marked ’31’ and the reef extending from the islet marked ‘25’ must be given room before setting the hook. The holding, in mud, sand and shell, is very good. The narrow part of the cove to the north gets plenty of current and, between surrounding reefs, is a very tight fit that is suitable for small boats only.

We headed to Joe’s Bay for the night. This snug anchorage lies midway along the north side of Fish Egg Inlet and includes a dramatic set of reversing falls. We prefer to anchor in the deep part of the cove in about 60′ and usually have the place to ourselves. If it’s busy, we take a line to the south shore. The drying rock opposite the island marked ’31’ and the reef extending from the islet marked ‘25’ must be given room before setting the hook. The holding, in mud, sand and shell, is very good. The narrow part of the cove to the north gets plenty of current and, between surrounding reefs, is a very tight fit that is suitable for small boats only.

Daunting Rapids

A tidal rapids leading to Elizabeth Lagoon lies at the head of the cove, creating a profusion of foam carried by current into Joe’s Bay. Although very interesting, this set of rapids must rank as one of the more dangerous lagoon passes on the coast, connecting as it does with a large, three-mile wide lagoon that is over 400′ deep in places. On an ebb, a significant waterfall is created at the lagoon entrance with up to a four-foot drop over a ledge that you only need to see once to be impressed.

We piled into the dinghy to take a quick look at the lagoon. If you’re heading into the lagoon by dinghy, be sure to depart it within an hour of high-water slack. As the Sailing Directions warn, the lagoon water is opaque, making it difficult to see dangers. Tides are referenced to Wadhams in Volume 7 of CHS Tide and Current Tables but if visiting the lagoon is a priority for you, it might be wise to observe the rapids from the east shore a day before to get an idea of the amount of current and the time available before the pass is too dangerous to navigate. The tide was close to turning, so we didn’t linger inside the lagoon.

We piled into the dinghy to take a quick look at the lagoon. If you’re heading into the lagoon by dinghy, be sure to depart it within an hour of high-water slack. As the Sailing Directions warn, the lagoon water is opaque, making it difficult to see dangers. Tides are referenced to Wadhams in Volume 7 of CHS Tide and Current Tables but if visiting the lagoon is a priority for you, it might be wise to observe the rapids from the east shore a day before to get an idea of the amount of current and the time available before the pass is too dangerous to navigate. The tide was close to turning, so we didn’t linger inside the lagoon.

That evening after dinner, while Reid strummed his guitar in the saloon, John stepped out on deck to look around and saw nothing but foam on the water. These white suds were flowing into the anchorage from Elizabeth Lagoon, blanketing the surface of the water and transforming the anchorage from glassy millpond to foaming bathtub.

Next morning, there was residual foam floating on the water as we left Joe’s Bay for our next anchorage, Waterfall Inlet. On the way to Waterfall Inlet there are two nice little passes between the numerous islands. One is the small pass north of Island ’99’ on Chart 3921. Currents in this pass seem to be two or three knots at most, and if you stay in the middle you’ll have at least 12 to 16′ of water.

A small waterfall does indeed flow into the east side of Waterfall Inlet at the mouth of a creek which leads, after a short but steep hike along the creekbed, to a lake. With no promising anchorage nearby, we decided to carry on to the south end of Waterfall Inlet where a very pretty anchorage lies in the inlet’s southeast corner, about half a mile from the waterfall. We tucked into the bight behind a small peninsula and, with a line ashore, were completely out of any wind. The holding is good in 35′ over sticky mud. Good anchorage for larger boats can be had in the middle of this cove in about 45′.

A small waterfall does indeed flow into the east side of Waterfall Inlet at the mouth of a creek which leads, after a short but steep hike along the creekbed, to a lake. With no promising anchorage nearby, we decided to carry on to the south end of Waterfall Inlet where a very pretty anchorage lies in the inlet’s southeast corner, about half a mile from the waterfall. We tucked into the bight behind a small peninsula and, with a line ashore, were completely out of any wind. The holding is good in 35′ over sticky mud. Good anchorage for larger boats can be had in the middle of this cove in about 45′.

This is one of those very rare and remote anchorages where time indeed seems to stop and where you can hear the birds and the cedars as the wind, high above, blow through the inlet. There is a small lagoon in the cove’s northeast corner that makes for an interesting, if short, dinghy trip. To the east of the lagoon is a small lake, which you can hike to along the creek bed.

Clutch of Islands

We spent our last day exploring Fish Egg Inlet at Green Island, which lies on the west side of Illahie Inlet. Formed by a cluster of islands, one of which is Green Island, the anchorage is one of the gems of Fitz Hugh Sound. Although four channels lead into the anchorage, the safest entrance is from the southeast. This sheltered anchorage can accommodate several boats, although we rarely see more than one or two. Depths throughout don’t exceed 60′, and we normally like to anchor in the west side of the basin in about 30′. The holding is superb throughout in soft, sticky mud.

Green Island itself isn’t any greener than most treed islands, but the islet lying close off its southwest corner is covered in brilliant green bramble. This islet forms a beautiful backdrop for anchored boats and is one of several islets awaiting exploration. To the northwest of the anchorage is a drying pass which wraps around the island marked ’63’ on Chart 3921. This opens to a small bay with numerous reefs worth exploring by dinghy or kayak. The waters off its west point, with its deep shelf, may be good for salmon fishing.

At the head of Illahie Inlet is another anchorage suitable for large vessels in about 50′. Recent logging along the west side of the bay has left roads leading along the shoreline that provide access to the nearby huge Elizabeth Lagoon.

It was soon time to leave the anchorages of Fish Egg Inlet behind us. The crew was getting restless, so it was time for some serious hiking on Calvert Island. As we headed across Fitz Hugh Sound toward Pruth Bay, a humpback whale surfaced in the distance, then performed a deep dive. It was a magnificent sight. These were the best of times.

—

Boating authors Anne Vipond and William Kelly have just released the new second edition of Best Anchorages of the Inside Passage, now available in bookstores and chandleries. Kelly and Vipond have cruised the coast of BC and Alaska for over 30 years, from the Gulf Islands to the Gulf of Alaska, and have included dozens of new anchorages in the expanded edition of their book, which covers the south and central coast regions of B.C.’s Inside Passage.

SIDEBAR 1

Fish Egg at a Glance

Charts: 3921 (scale 1: 20,000), 3935 Entrance

Lat/Long: (Entrance) 51˚ 37.8’N, 127˚ 50’W

Pros: Numerous anchorages, good fishing and dinghy exploring. Great haven from most winds. Most anchorages quiet with great scenery.

CONS: Except for a few logging roads at the top end of Illahie Inlet and the east end of Oyster Bay there are few obvious hiking opportunities.

MUST DO: Explore several anchorages, see the reversing falls at Elizabeth Lagoon in Joe’s Bay.

SIDEBAR 2

The Humpbacks are Back

The Humpbacks are Back

It used to be, back in the 1980s, that sightings of humpback whales were rare in BC waters. If you wanted to see humpbacks, you had to head north to their summer feeding grounds in Alaska. Since then, humpbacks have returned to local waters in steadily increasing numbers. Each summer these large whales are regularly sighted in several areas of the BC coast, including Juan de Fuca Strait and the north end of Johnstone Strait. But one of the best places to view these magnificent mammals is just north of Cape Caution, in Fitz Hugh Sound, where sightings are a daily occurrence in the summer months.

Out on the water, the first sign of a feeding humpback is a plume of mist, which indicates the whale is surfacing for air. Often a humpback will surface several times, its back appearing briefly above the water, before it performs a deep dive with its tail straight up above the water. Sometimes a humpback will, without warning, heave itself clear out of the water and land, belly-flop style, with a gigantic splash. In the past, when humpbacks were hunted by commercial whalers, their surface activity and near-shore feeding made them easy targets. Protected since 1966, the humpback’s acrobatics – breaching, lobtailing, diving – now thrill whale-watchers armed with cameras.

Humpbacks are not aggressive, although rival males will sometimes smack one another with their barnacle-studded tails. However, due to a humpback’s unpredictability and immense size, boaters should be careful not to get too close to one of these gentle giants. There have been incidents in which displacement boats have been bumped by one of these whales, and of fast-moving powerboats colliding with one. Because humpbacks often seem unaware of vessels in their vicinity, concerns are being raised about their safety should oil tanker traffic increase on the BC coast. A study recently released by the federal government on the recovery strategy for humpback whales cites shipping traffic as a threat to their critical habitat.

The number of humpbacks now feeding each summer in BC waters is estimated to be about 2,000. Whatever the exact number, the species is experiencing a slow but steady growth in population. As winter approaches, the North Pacific humpbacks head south to spend their winters in Hawaii or Mexico. While in tropical waters, they engage in mating rituals. This is when the males serenade the females with repeated patterns of sound, these “songs” performed at depths of 60′ or more. Winter is also when the females give birth following a 12-month gestation period. Calves are born without a blubber layer and nurse on their mother’s milk, which contains 50 percent fat.

When a humpback reaches adulthood, it averages 45′ long and weighs up to 40 tons. Its large flippers provide maneuverability and the pleats on the sides of its mouth can create a pouch large enough to hold six adult humans. When feeding, a humpback blows columns of bubbles that create a ring around a school of fish, which it then lunges at with its mouth wide open. Seabirds, attracted by the water disturbance, feed on the krill and herring that swim to the surface. Such bird activity is another sign for alert boaters to look for when cruising in waters we share with the humpbacks.

Photo Captions:

1) Joe’s Bay

2) Fish Egg Inlet

3) Joe’s Bay

4) Joe’s Bay is a snug anchorage on the north side of Fish Egg Inlet.

5) Waterfall Inlet

6) The entrance to the lagoon in Joe’s Bay is interesting but dangerous, with a significant waterfall on the ebb tide. Enter only near high-water slack.

7) Humpback whales are sighted regularly in Fitz Hugh Sound.

CREDIT: Michael DeFreitas