Ask Andrew: The great bilge oil discharge conundrum

May 9, 2022

I’ve always thought that where safety is concerned aboard, it should be the same whether the boat is a commercial, passenger-carrying vessel or a privately owned sail or power boat. In most cases, safety requirements in terms of construction and safety-gear is comparable, based on vessel size and use – but one of the main differences that has always annoyed me is the requirements for separate water-tight bilge compartments in commercial craft, while that the majority of production sail and power boats don’t require any compartment division.

This means that while bulkheads in privately-owned boats are structural, they are not necessarily watertight: water will flow from bow to stern (or vice versa), and will collect in the lowest part of the bilge. This also means that if damage occurs anywhere on the boat, the entire boat will fill. In commercial craft, sections are required to be watertight: if damage occurs, only the compartment that is damaged will fill with water, the hope being that despite one compartment flooding, the boat will still stay afloat.

In a commercial boat, each compartment would be required to have it’s own bilge pump to allow any water entering or collecting (through through-hulls, stuffing box, rainwater, seawater or damage) to be pumped out independently. The compartments that are least likely to accumulate water regularly would have bilge pumps operated with a simple on/off switch. A compartment that is more likely to collect water (for instance, where the stuffing box Is located – where the propeller shaft runs through the hull) would have a bilge pump operating on a float switch: as the water level rises, the float engages and turns the pump on. Once the water level drops, so does the float, and the pump stops running.

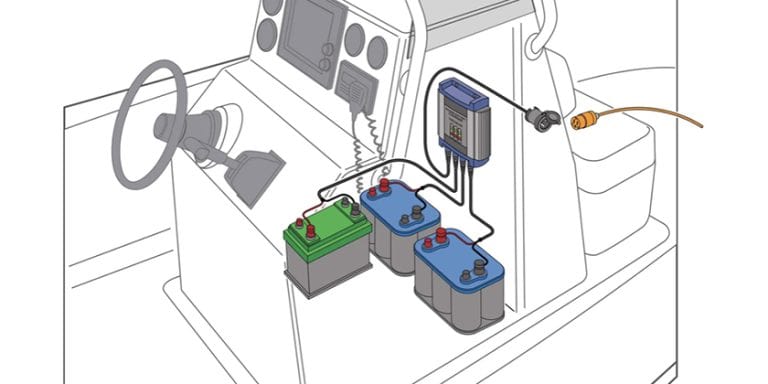

In a privately owned boat – either power or sail – the bilge is essentially one large compartment. Water will collect in the lowest part of the bilge, which is usually near the engine. For both safety and convenience, a single bilge pump that operates on a float switch is sufficient and practical.

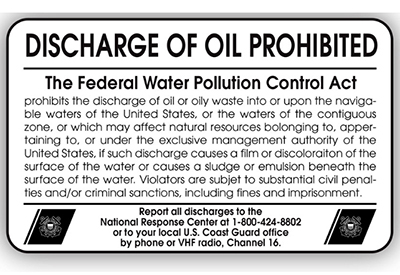

Here’s where things become a bit complicated: Most boats in Canadian waters (with an inboard engine) are required to have a placard affixed in or near the engine space that states that it is illegal to discharge oil into Canadian waters

In a commercial vessel, it’s relatively easy to comply: before engaging any bilge pump, make sure that the water in that compartment isn’t full of oily water before engaging the pump. Any water-tight compartment that has a bilge pump operating on a float switch will not be connected to areas that are oily or have the potential to pollute (the rule of thumb is that the engine compartment – where oil, fluids, dirt and dust are present – would have a bilge pump that is not operated on a float switch, so that there is no chance of accidental pollution.

note the bilge pump, sitting in oily water, under the engine

note the bilge pump, sitting in oily water, under the engine

Here’s the baffling part: The bilge pump on a typical privately owned sail or power boat is located near the engine. Any spilled oil, gear lube, power steering fluid, hydraulic oil, coolant or fuel will land in the bilge and head straight for the bilge pump. If water has accumulated, a float activated pump will pump this filthy oily disgusting water overboard, which contravenes the requirement on the placard stating that discharge of oily water is prohibited and can result in hefty fines (let alone the environmental damage that may be caused.

On one hand: the boat is designed to have a bilge with the lowest point at or near the engine. It is practical and safe to have this bilge pump on a float switch so that if water accumulates when no-one is aboard, the boat will be protected from flooding

On the other hand, we have a legal and environmental requirement to not discharge oil overboard.

How do we reconcile the two?

the sheen of oil on the waters surface indicates that perhaps someone has dumped their bilge here

the sheen of oil on the waters surface indicates that perhaps someone has dumped their bilge here

1) Whenever performing work on the engine where there is a chance that oil, fluids, fuel or coolant can spill, disconnect the bilge pump to eliminate the chance that it accidently engages until work is complete and the area is cleaned up.

2) Keep the bilge clean – keep oil, dirt, detritus to a minimum, and give the bilge area regular cleans with an appropriate cleaner

3) If concerned about leaks or pollution from the engine, consider installing a pan below the engine to collect any spills before they hit the bilge

4) Take advantage of modern components and solutions, such as dripless stuffing boxes, which can drastically reduce the amount of water the enters the boat

5) Keep bellows, through-hulls and seacocks well maintained. The less water entering the boat, means fewer cycles of the bilge pump moving water overboard, reducing the chance of accidental pollution

6) Before moving bilge pumps, or making compartments water-tight, consult with a qualified marine tech who can advise you on the pros and cons of making changes that can impact safety and stability.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.