Winterization Isn’t Like Your Dad Did It: Modern Methods For Modern Boats

Winterizing isn’t like your dad did it: Modern methods for modern boats

By Andrew McDonald, Lakeside Marine Services

“They don’t make ‘em like they used to”, is a phrase that many of us are familiar with. Most of the time it is in reference to a bygone era of better, and it’s used to lament the sorry state of what we have today. It is a phrase that can be applied to many areas of our lives: architecture, art, furniture, tools. Boats? I would argue that they don’t make them like they used to. But, is that lamentable, or is it progress?

Progress, I think. With this concept in mind, as we enter another season of putting boats to bed for the winter, why do we winterize as we always have? We need to adapt and update our winterizing methods to keep up with the evolving systems on modern boats.

In our Parent’s and Grandparent’s time, winterizing was simple. Drain the water. Run antifreeze through the engine. Disconnect the battery and store it. Simple.

Technology, space-age materials, modern conveniences, innovative products, applications from other industries (home building, automotive technology, military), as well as modern environmental concerns have changed every aspect of boat maintenance – and this is most acutely seen in the way modern boats should be winterized.

Winterizing achieves two goals: it protects the on-board systems from freezing damage in the sub-zero temperatures of northern climates, and it prepares the systems for long-term storage. Each on-board system has its own particular needs, and these needs have evolved with new products, treatments, materials and system complexity. It’s tough to keep up so, I’ve spoken with some experts in the industry – here is a breakdown of their recommendations:

Engine

Winterizing the engine has become a strategic process; several systems need to be addressed and it’s most efficient to complete the tasks in order; some in the water, some on the hard.

The Lubrication System

Oil allows the moving parts inside the engine to move freely – it lubricates, cools and optimizes efficiency. Manufacturers recommend that engine oil and filters be changed every 100 hours, or annually (whichever comes first). Changing the oil in the fall makes sense; it removes any water, contaminants, particles and debris from settling inside the engine over the winter and gives a smoother start next spring. It’s best to change the oil when the engine is warm and just before the boat is hauled. Run the engine up to temperature, stop, drain the old oil, change the filter and fill with the recommended oil. As part of this process, check/replace transmission fluid, power steering fluid and hydraulic fluids. On sterndrive units and outboard engines, drain and replace gear lube.

The Fuel System

At the same time, the fuel system can be addressed; fuel tank, lines, filters, carburetor, injectors and spark plugs.

One of the ‘hot button’ issues in modern boating is ethanol in gasoline. This needs to be understood when preparing for winter.

Ethanol blended fuel has become the standard at highway fuel stations. Currently, E10 (10% ethanol to 90% gasoline) is common. There are advantages in cars but, in boats with fuel tanks that have to be vented for safety reasons, ethanol causes a number of significant problems:

Ethanol blended fuel has become the standard at highway fuel stations. Currently, E10 (10% ethanol to 90% gasoline) is common. There are advantages in cars but, in boats with fuel tanks that have to be vented for safety reasons, ethanol causes a number of significant problems:

1) Ethanol is ‘hygroscopic’ – meaning that it draws the moisture from the air into the fuel. A litre of E10 gasoline (with 10% ethanol) can hold approximately 2 teaspoons of water in suspension. When the gasoline reaches that level of water absorption, phase separation occurs. The ethanol/water blend separates from the gasoline and drops to the bottom of the tank.

2) Ethanol is an octane booster – when the pump says 87 Octane with 10% ethanol, the ethanol contributes to that octane rating. When phase separation occurs, the ethanol/water blend separates and takes some of the octane along with it. The gasoline that is left won’t fire properly in the engine.

3) Because of this, gasoline with ethanol has a shelf-life of about 90 days. Any fuel left in the tank at the end of the boating season, may not have enough octane to effectively burn at start-up in the spring. This is also why ‘premium’ fuel is often recommended. If the ethanol separates from 91 octane fuel (taking with it some of that octane), the hope is that there is still enough octane rating remaining for the fuel to fire in an engine designed to run on ‘regular’ 87 octane.

4) Newer engines have been adapted to manage E10 gasoline, but engines manufactured before 2005 have components that can be damaged by E10 fuel.

5) Ethanol is an alcohol; it can damage gaskets, carburetor ports and floats, fuel lines and fuel filters

6) Ethanol is highly corrosive. It can damage the metal components in the fuel delivery system

Luckily, marinas have adapted to the challenge, and most marina fuel docks will offer ethanol-free fuel.

To combat the negative effects of ethanol, it is recommended that fuel tanks be filled prior to long-term storage. It only takes a 7 degree change of air temperature for condensation to form on the inner walls of fuel tanks – meaning that the difference between night and daytime temperatures over the winter months could cause condensation to form each day, accumulating water until the fuel undergoes phase separation and it becomes unusable. Keeping the tanks full reduces the air space over the fuel eliminating the space for condensation to accumulate.

Just as important as keeping tanks full, is the use of a fuel additive to combat ethanol’s effects; an additive that protects against corrosion, phase separation, and loss of octane.

A number of manufacturers have introduced fuel stabilizer products: ValvTect, K100 Fuel Treatment, Quicksilver’s QuickStor, Starbrite’s StarTron, Captain Phab and CRC, to name a few.

Next, the fuel system should be treated. The engine should be run for a few minutes to run stabilized fuel through the fuel lines and filters. With the engine still running, the fuel tank shut-off should be closed off – draining the fuel lines and carburetor. As a final step, fogging oil should be sprayed into the carburetor, to leave an oil film on the carburetor and cylinder walls, protecting these components from corrosion.

In fuel-injected engines (with no carburetor) a mixture should be prepared in a remote fuel tank and the engine allowed to run on this mixture as a replacement for the fogging procedure. The recommended mixture is a ratio of 10:1:0.15 of Gasoline, fuel stabilizer and 2-cycle outboard oil.

In a diesel engine, the same result (coating the cylinder walls with a protective film of oil) is achieved by spraying oil into the air inlet as the engine is cranked.

Treating a diesel tank is just as important. Modern diesel fuels are ultra-low-sulphur, which tends to hold more water and go bad faster than older diesel formulations. A modern diesel fuel additive should contain a biocide to prevent and kill bacteria, corrosion inhibitors, stabilizers, detergents, dispersants and a cetane improver (cetane is, to diesel, what octane is to gasoline – an indicator of the combustion speed and the compression needed to fire).

The Cooling System

Engine cooling systems are of two types: Open and Closed. The open system draws seawater into the engine, circulates it and spits it back out with the exhaust. The closed system uses ethylene glycol antifreeze (the toxic orange/green/yellow, sweet smelling stuff found in car radiators). The closed system circulates antifreeze and works with the open/seawater system to keep the ethylene glycol cool, via a heat-exchanger.

Some marine engines have just an open cooling system. Others use a combination of open and closed. In either case, seawater is drawn into the engine to cool it. If seawater is left inside the engine to freeze, the water expanding can break or crack internal walls, exhaust manifolds, engine blocks, and bolt-on components.

Some marine engines have just an open cooling system. Others use a combination of open and closed. In either case, seawater is drawn into the engine to cool it. If seawater is left inside the engine to freeze, the water expanding can break or crack internal walls, exhaust manifolds, engine blocks, and bolt-on components.

The process of winterizing is designed to remove the seawater and replace it with an antifreeze solution that is capable of protecting the engine from freezing damage.

The modern engine block hasn’t changed a whole lot, but the bolt-on systems and the improvements in the efficiency of engine cooling has changed significantly.

Engines from 20 years ago have as few as 2 drain points: the engine block and the exhaust manifold. Modern engines can have as many as 9 drain points, including the thermostat housing, the power steering cooler, the fuel cooler, water pump, block and manifolds.

Step 1: Drain each of the drain points and ensure that water has completely drained from the engine. Crank the engine over (without starting) in order to purge any water trapped in the seawater pump. Ensure that strainers, coolers and mufflers are also drained

Step 2: Choose the correct antifreeze for the job. A closed cooled system will use ethylene glycol, but the open cooling system (where water cools when in use) should be winterized using propylene glycol (also called RV antifreeze, water system antifreeze, or ‘the pink stuff’).

Propylene glycol is readily found, but not all mixtures are the same. Mercury Marine recommends that the glycol contains a rust inhibitor and is recommended for use in marine engines. Quicksilver and Starbrite make a high-quality marine antifreeze.

Propylene glycol is available in different strengths: -50 degrees F and -100 degrees F are common options. Keep in mind, though, that as the antifreeze is added to the engine (whether drained completely or not), any water it comes into contact with will dilute it, lowering its strength. Test the strength of the antifreeze as it flows out of the engine using a refractometer to determine the temperature that the diluted antifreeze will protect to.

Step 3: remove hoses from thermostat housing and fill with antifreeze until the engine block is full. Reinstall hoses.

In many diesel engines, antifreeze needs to be ‘poured’ in in various ways, or run through. Always check the winterizing procedure in the service manual for your engine’s make and model. Propylene glycol can damage neoprene or nylon components – so ensure that when pouring/running antifreeze through a diesel engine the water strainer and the impeller are protected from the damaging effects of the antifreeze.

Step 4: In boats with stern drives, and in outboard engines, leave the drive trimmed all the way down/in.

Step 5: Test the strength of the antifreeze using a refractometer. A sample can be taken at the engine’s exhaust port, or by slightly opening a block drain plug. This will allow you to confirm the maximum cold temperature so that the engine will not freeze. Similarly, in boats with a closed cooling system, the ethylene glycol strength should be checked to ensure that it will meet the low freeze mark.

Step 6: Seal off any openings (exhausts, air inlet, water inlet) to prevent damp air from causing damage.

Fresh water system

Modern boats can have complicated plumbing systems, including water-cooled refridgerators, air-conditoning units, electric flush toilets and many pumps designed to move water. Each of these items requires proper winterization.

The boat’s holding tank should be pumped out prior to haul out, and a septic cleaner run through from the head to the holding tank. Products like Head-o-matic’s ‘Shock Treat’ are ideal for this purpose.

Next – drain water from every area of the boat. This list should include:

1) Fresh water tank (water pump and open faucets until the tank is empty)

2) Disconnect the shore water line

3) Drain the bilge completely (a sponge can help remove the last few mm)

4) Drain the hot water tank by opening the drain cock. Bypass the hot water tank so that any antifreeze run through the lines won’t enter the hot water tank

5) Disconnect the water lines at the lowest point and allow the lines to drain

6) Drain every sea-water strainer by opening the drain nut

7) Pump out any water in the head

8) Drain the shower sump

9) Use compressed air to blow through the water lines

10) Run antifreeze (the same polypropylene glycol used for the engine) through the lines. I tend to use a hand-pump, but the boat’s electrical pumps can be used as well

11) Run antifreeze through the head, by disconnecting the water inlet and pouring antifreeze in as the pump/flush is engaged.

12) Pour antifreeze in the shower drain into the sump and run the pump until it flows overboard

13) Pour antifreeze in the bilge areas and run the pumps until it flows overboard

14) Pour antifreeze into the livewell areas and run the pumps

15) Pour antifreeze into the air-conditioner pump inlet and run the pump until it flows overboard

16) Run antifreeze through any other fresh water source: cockpit showers, wash-down faucets, refrigerator lines, etc

Many modern boats utilize PEX tubing (crosslinked polyethylene pipe) which is very versatile and well suited to the marine environment. It is inexpensive to buy and install and a simple system to maintain. It tends to stretch rather than crack or break when frozen water expands inside, but still must be drained and winterized to prevent long-term damage (especially in the connectors).

A note here on running antifreeze through pumps, lines, heads and other potable water fittings: propylene glycol has been proven to damage neoprene and nylon components. Running antifreeze through pumps that use neoprene diaphragm risks future damage. Many modern pumps employ a centrifugal design that allows them to safely pump antifreeze. Modern marine toilets can also be problematic: the joker valve (the valve that allows waste out and prevents it from flowing back into the bowl) is particularly susceptible to damage from antifreeze.

A properly fastened and torqued terminal compared to the corroded terminal that wasn’t done correctly. Photo: Rolls Battery

A properly fastened and torqued terminal compared to the corroded terminal that wasn’t done correctly. Photo: Rolls Battery

Batteries

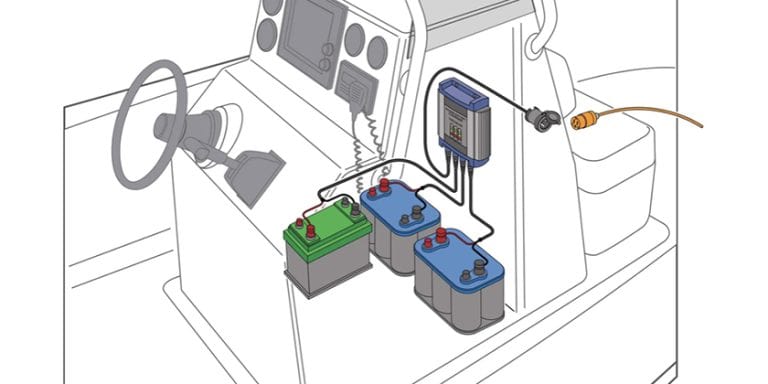

Flooded cell batteries must be maintained correctly in order to winterize properly. The fluid inside a flooded battery changes its chemical composition depending on its state of charge: a fully charged battery is primarily sulphuric acid, where a discharged (partially drained) battery is full of water. Water freezes, while sulphuric acid does not. So, of prime importance is ensuring that batteries are fully charged before the boat is left in freezing temperatures.

In order to keep the batteries in a charged state, they should be disconnected while stored. Theoretically, a disconnected battery will have the same charge once reconnected in the spring as it does when put in storage in the fall.

This is what can happen to batteries that freeze. Photo: Rolls Battery

This is what can happen to batteries that freeze. Photo: Rolls Battery

Prior to winter storage, and when reconnecting in the spring, the battery should be load tested and the battery terminals should be torqued to the manufacturer’s specifications

Electronics

Modern LCD Multifunction displays (both touch and non-touch) are designed to be stored at temperatures as low as -30 degrees C.

Modern electronics are designed to withstand winter storage without

being removed.

The connectors are designed to stay plugged in – push in, twist lock style connectors are watertight and designed to prevent any terminal corrosion. If connectors are left unplugged, they should be coated in a conductive anti-corrosion grease.

Electronics should be powered down before removing the battery cables from the batteries. Similarly, any network or periphery cabling should have devices powered down before unplugged or removing source voltage. In the spring, when reconnecting batteries and devices, ensure that the circuit protection (fuse or breaker) is installed correctly, to prevent damage from power spikes as the batteries are reconnected.

Today’s boats can go further, faster, and with better fuel economy. Modern conveniences are commonplace aboard. The latest gadgets can be employed. Space-age materials make them lighter, faster and stronger. Most maintenance tasks (including winterizing) are within reach of the average boater. If winterizing tasks appear overwhelming, or you are unsure of the correct steps to take in your boat, speak to a reputable marina to have a qualified marine tech take care of this process for you.

They don’t make boats like they used to. But, we enjoy them just as much.