The Ins and Outs of Working on a Superyacht

By Marianne Scott

An estimated 10,000 yachts measuring 100 feet or more are afloat on the world’s oceans. They congregate in places like Monaco, St. Tropez, Fort Lauderdale, Antibes, and Antigua. Some yachts are used for private luxury cruising – Oman Sultan Qaboos, for example, shares Al Said, his 508-foot yacht, only with his 65 guests (and 140-member crew). Other big yachts offer opulent charters serving paying guests. Many yachts move between the Mediterranean and the Caribbean following the seasons.

All these pleasure palaces share one common need: Crew. Crew that range from those scrubbing decks and polishing chrome to captains with high-level certifications, years of experience and seatime, who are trusted to safeguard hundreds of millions of dollars worth of floating castles and their passengers.

Superyacht work entices many people: It’s a chance to vicariously experience the life of the 0.1 percent, live in lavish surroundings, visit exotic parts of the world, meet educated and interesting people and, on chartered yachts with big tips, make a very good living. Those are the pros of superyacht employment. The cons are that the work can be relentless: You may have to accommodate super-demanding guests; you’re likely to share a cramped cabin with a stranger; sexual harassment, especially for women, is a factor; and your behaviour must always be professional and courteous regardless of circumstances.

Swell, a converted tug, now a passenger vessel cruising the Inside Passage.Courtesy Alex Ruurs

Swell, a converted tug, now a passenger vessel cruising the Inside Passage.Courtesy Alex Ruurs

If you’d like to work on one of these yachts, either as an interlude in your career track, or as a long-term profession, you must meet a number of criteria. The absolute minimum certificate, compulsory for even the least skilled jobs, is the Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers, known universally as the STCW. The STCW covers first aid and CPR, personal survival techniques, personal safety and social responsibility, fire prevention and fire fighting, and security training.

Courses are offered in many countries and locations – simply search for the term and you’ll find a course near you. Prices vary greatly, so shop around.

What kinds of jobs are available aboard superyachts? They range widely: The most common positions are captain, first/chief officer, mate/bosun, deckhand, chief engineer/second engineer, chief steward/stewardess/purser, junior steward/stewardess, chef, sous-chef, and crew cook. Some are day jobs, others can last a week, a month, or even a year. They can be full-time/permanent, part-time, or rotational.

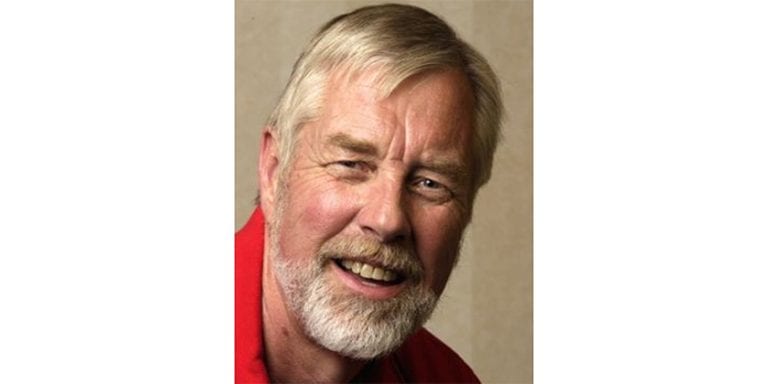

I asked Capt. Ted McCumber, who has decades of experience skippering megayachts – the last being the 274-foot Savannah – what he looks for in a crew member.

“For a beginner,” he said, “it helps if that crew member is well-rounded with a hospitality background…our industry is the hospitality industry. A big yacht is a moving boutique hotel. Experience in serving people at all levels counts. And I don’t want fly-by-night folks. I need a year’s commitment at least. It builds crew cohesion.”

Finding a job. After obtaining the STCW, some people go “dock walking” in locations where the big yachts gather. They talk with crew, ask for leads, use the basic networking approach. They also list themselves on job websites. Dylan Stephanian, who flew from Toronto to Fort Lauderdale, was in his STCW course when a guy walked in and asked, “Anyone interested in a deckhand job?”

“I was the only who answered,” said Dylan, “and three days later I was aboard a 60-metre powerboat delivery from Florida to Malta. I cleaned and stood watch.”

Afterwards, he flew to Nice and took day jobs, usually cleaning and polishing. “I took any offer that came along,” he said. “You must be willing to start at the bottom and show your stuff. Meanwhile, I kept asking everyone if they knew of an opening. It worked and I next crewed on a sailboat delivery to Germany.”

Northern Dream, a 130-ft Wesport. Photo courtesy Nat Klein

Northern Dream, a 130-ft Wesport. Photo courtesy Nat Klein

Dana Glover found employment as a freelance stewardess. She took her STCW course in Miami and used her experience in event management to become acquainted with boat show managers.

“I chatted up people,” she said. That landed her a job on a 103-foot yacht cruising the Caribbean for eight months. Part of a crew of three, she served as stewardess (lots of housework) and cook. She had no experience as a cook, but managed. “I scoured the Internet for recipes. It helped that I could buy really good ingredients.”

Since then, Dana has been aboard yachts measuring up to 300 feet, cruising from the Caribbean to Maine – always as a freelancer rather than a contract employee. She likes taking time off between postings and prefers smaller boats.

“The disadvantage of freelancing,” she said, “is that there are no benefits.”

Yacht Crew Agencies are just like shore-based employment bureaus – they can help you find a job (one example is www.yacrew.com/). Agencies are stationed around the world – and usually, the yacht owner pays the placement fee, not the crewmember.

Arata Tanaka in his chef uniform in Antibes, France.

Arata Tanaka in his chef uniform in Antibes, France.

Crew agencies assess employees by their experience, longevity on similar yachts, and references. If requested, the agency will perform drug testing and criminal background checks.

“We check references and verify certifications,” one recruiter told me. “References are what get people the jobs. These show whether they get along or have attitude problems, and if they’re willing to work and learn.”

Seattle-based crew agency Lacasse’s Rita Kapuscinski, who places crew around the world, added that captains look for healthy, disciplined staff, non-smokers preferred.

“The competition is fierce as there are many, many people looking for these jobs,” she said.

Kristina Long had gained racing experience on her mom’s sailboat, then, after university, worked as part of delivery crews on various boats. Having passed her STCW, she signed with crew agents and began “day work”.

“It means you don’t live on a boat,” she said. “You’re temporary help, polishing the boat, cleaning the engine room, serving as chambermaid. It’s certainly not all glamour.” She travelled to Antigua, and subsequently served on ten different yachts, building her resume and securing references. Virgin’s Richard Branson was one celebrity client. Along the way, she studied and earned more certificates, so now she can apply for chief mate jobs, which include navigating and managing crew.

A superyacht among the freighters on the Suez Canal. Photo Marianne Scott

A superyacht among the freighters on the Suez Canal. Photo Marianne Scott

“It may be discriminatory, but yacht owners and charterers like young, fit, and attractive people, non-smokers, usually under 35,” Kristina said. “It’s age-limited unless you earn higher-level certificates, get seatime, and move up the hierarchy. And I advise young crew to cover up tattoos and lose their piercings.”

It helps a great deal if you have diversified skills (to qualify for higher-level jobs, several agencies offer courses; www.superyacht-crew-academy.com is one example). When you search job sites, you’ll learn many jobs demand more than one competency. Besides being a steward/stewardess, there’s a call for such skills as yoga instruction, personal training, massage, manicures, hair dressing, running water toys like kite boards and jetskis, teaching diving and spear fishing, or operating tenders. Some yacht owners request tutoring for their on-board kids; I read one request for a Mandarin- and English-speaking teacher. A research vessel asked for a stewardess with photographic and scientific skills.

Eviva, a 163-foot Westport carries its own helicopter and 11 crew

Eviva, a 163-foot Westport carries its own helicopter and 11 crew

Like soldiers, sailors travel on their stomach. Aboard superyachts, with charter guests paying from US$150,000–350,000 per week, the food better be awesome. Everything must be fresh and artfully presented. Moreover, some private yacht owners are highly specific in their search for chefs, asking for expertise in ethnic foods and healthy, low-carb, allergy-proof, or vegan fare.

You can be a single chef, like Dana Glover, or part of a team. I spoke with Arata Tanaka, the third chef on the 408-foot Katara, owned by the former Emir of Qatar. The yacht carries a helicopter and is worth around US$300 million. When I reached Arata by phone, he wasn’t allowed to reveal his location for security and privacy reasons. Somewhere in the Med, he said.

Arata trained as a sushi chef in his native Japan, completed Camosun College’s Red Seal Cook course, and worked in high-end restaurants and bakeries in Victoria. Ready for a change of scenery, he took his STCW in Fort Lauderdale, flew to Antibes and immediately visited a crew agency.

“The company improved my resume,” he said, “and I took an eight-day trial run on a 131-foot private yacht with six crew. It was breakfast, lunch, and dinner, starting at 0600 and ending at midnight, every day. Afterwards, I revisited the agency and my new reference allowed me to work on Katara with its crew of 60.”

Capt. Ted McCumber on the bridge of the 274-foot Savanah

Capt. Ted McCumber on the bridge of the 274-foot Savanah

The crew includes 29 nationalities, with English being the universal language. Seven crew cook in two galleys, each taking a shift. The chefs do it all: Prep, cook, present the food, and clean up.

“After the first two weeks,” said Arata, “I felt my brains coming out of my ears.”

Despite the demanding job, Arata liked the new adventure, especially the chance to visit exotic places such as Spain, Mallorca, France, Greece, Dubrovnik, and Venice.

Superyacht jobs can offer high-level careers. The 274-foot Savannah, for example, employs four engineers. Capt. McCumber told me that for yacht engineering positions, a marine engineering degree from schools like BCIT, Cal Maritime, or Memorial University is a huge step up.

“It will give you a four-year degree and a license, and also an option of entering commercial shipping after yachting,” he said. “Moreover, yachts are now getting so big you need higher-level licenses the average crew member doesn’t have.” He noted that having knowledge and experience in integrating and troubleshooting the complicated onboard electronics – navigation, fuel control, entertainment devices, and security – are highly desirable talents.

After Eight, a 151-ft yacht in Haro Strait, BC. Photo Marianne Scott

After Eight, a 151-ft yacht in Haro Strait, BC. Photo Marianne Scott

Chief Engineer Peter Boyce works on a 295-foot yacht with a three other engineers (second engineer, electrical engineer, and motorman).

“I love my job,” he said, “My days are spent primarily facilitating the engineering team, coordinating with contractors, complying with flag regulations, managing ships’ inventories, and working with the captain to ensure we operate at the highest level of safety and efficiency.” He’s worked on yachts for 20 years but still finds that every day presents new challenges and learning opportunities. “Nobody pays much attention to engineers until there are breakdowns, and 90 percent of the time you get a radio call, it’s bad news.”

Dylan Stephanian. Photo Marianne Scott

Dylan Stephanian. Photo Marianne Scott

But Peter also values the rewards. “The pay is good and we can operate with a certain level of autonomy,” he said. “Compared with the rest of the crew, engineers avoid the drama that seems to happen when you place a bunch of different personalities in the confines of a ship.”

Finally, do superyacht jobs pay? Several websites provide earning ranges; I found a good list at ypicrew.com/. Here’s a sampling of US$ monthly pay ranges (yacht size influences pay): Captain, $6,000-18,000; third engineer, $3,450-6,300; sous-chef, $3,700-6,900; second stewardess, $3,100-5,700. Remember, you also get room-and-board and travel pay.

One crewmember expanded on the financial benefits of charter vessel employment. “Guests can be very trying,” he said. “Sometimes, they’re not forgiving, work you long hours, yet often leave massive tips. The norm is $1,000 per person per week. You work like a dog, but get paid like a king.”