Cowichan Bay to Genoa Bay – Almost the Gulf Islands

By Catherine Dook

Inuksuk rides peacefully at anchor in Genoa Bay.

“So you’re going offshore to Genoa Bay,” said an old salt at coffee that morning. Genoa Bay was 15 minutes away from our homeport of Cowichan Bay and hardly counted as offshore, but it was our first destination that fall. The fog had socked us in all that morning, so John and I drank coffee and gossiped with the neighbours while waiting for the weather to lift. We’d provisioned with cans of chilli, a sack of apples, and tanks full of water. We’d tested the engine and the anchor winch. We were ready.

Our vessel, Inuksuk, was heavy, and John suffered mild anxiety that even though we planned to undock bow-first, evil forces over which we had no control would influence his steering through the rabbit-warren that is our marina and cause him to hit someone else’s boat. The only other rudder I’ve ever seen as proportionately small as ours was on the ocean-going Cutty Sark in Greenwich, England. We ate lunch under her suspended hull, almost too astonished by the miniscule size of her rudder to swallow our tea and Victoria Sponge. “I bet,” John remarked, “The Cutty Sark didn’t steer either.”

Cleaning the dinghy at Cowichan Bay.

In the end, it took a village to undock us. Horst on the bow line, Screaming Liver on the stern line, and Ashley and Arthur on the breast line, while John steered and I fussed and caught lines the men threw to me. “Stern line first, Catherine!” John yelled, and I walked to the rear of the vessel pretending I’d had important business at the bow.

“Clear!” I yelled at John as we slid bow-first out of our slip. “Clear!” It relieves tension when you yell.

Our neighbours gathered on the dock with a self-congratulatory air, as if they’d done well by seeing us off safely. On the way out we missed hitting all the neighbours’ boats. You can always count on a group of neighbours to help you if they know your boat is clumsy and they own a boat you might hit on the way out.

Our vessel slid through the water slick as slick. Our bottom was so clean you could eat dinner off it. I tidied the lines the men had flung on the deck and unfastened our three mismatched fenders, reattaching them to the stern. I began to cheer up.

I’d bleached and washed all our towels before we left, and weren’t clean towels a reason for happiness? And because John had checked the anchor winch, I could probably anticipate a flawless anchoring, provided I could remember the colour code on the chain as it shot past me. And wasn’t the weather forecast as optimistic as a federal government election promise?

The water reflected the sky. Crab pots lay in the water here and there; John dodged them expertly, then before I could work myself into a state, we slid into Genoa Bay between the two markers – red to starboard, green to port.

Genoa Bay was full of sunlight. There was mist on the mountaintops and trees everywhere. And it was quiet – a shout, a crying gull, and our motor.

We anchored in 33 feet of water, tucking ourselves in behind the marina, and I grabbed the winch handle and strode forward, full of confidence. This time I DID have important business at the bow. I loosened the anchor then on John’s signal, I dropped it.

The two piles of iron filings in Genoa Bay are all that’s left of the saw mill.

As the chain rattled past me, I remembered we’d agreed last year the markings would have to be repainted. The red paint that should have been visible at 20 foot intervals had dissolved out of sight and sunk to the bottom of the chain locker. Then – white paint! White paint! 150 feet! Saved! I counted to four, then slammed on the brakes and waved John back.

Our CQR caught almost immediately.

Sometimes the fates converge on you with such happy effect that your life is drop-kicked into a class with the upper crust, like power boaters.

The visibly steep foreshore at Genoa Bay.

The visibly steep foreshore at Genoa Bay.

I remembered that years ago I used to worry the whole time we were anchored that I wouldn’t be able to pull the anchor up again. Now I knew that the winch was repairable if you stuck wires together, the manual winch works fine in a pinch if you have to use it, and the goose-grease at the bottom of Genoa Bay is soft and slippery and easy to slide an anchor out of.

I remembered that I used to worry we’d drag, but now I know that given a CQR knock-off and 200 feet of chain out, our boat is going nowhere while everyone around us has hauled anchor and is spending the night resetting it or motoring in circles. I know that if we do drag, the strategy is to start the engine, winch the anchor up, and slink away before anybody sees us.

So we drank coffee in the cockpit and drifted in the sun.

I looked around me. Genoa Bay. The mountains on three sides of us were furred with trees of such green-ness that you would hardly think Vancouver Island had any water restrictions at all, though a sign on the road said we were at Stage 3. I rinsed some laundry in our fresh water and hung it out to dry.

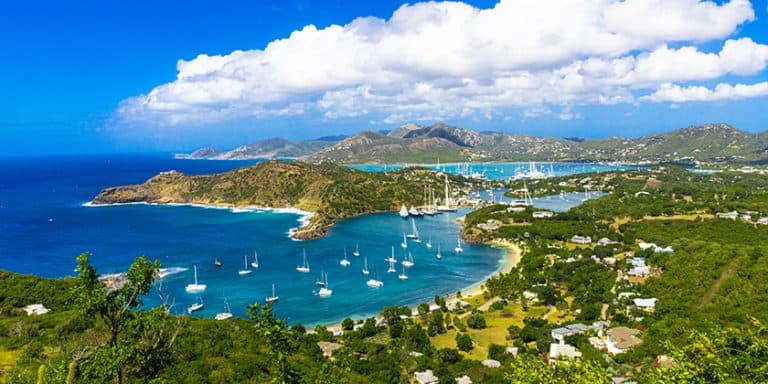

Genoa Bay.

The first European vessel to spot the bay may have been the s/v Hecate, whose captain chose to disembark his settler passengers at Cowichan Bay instead.

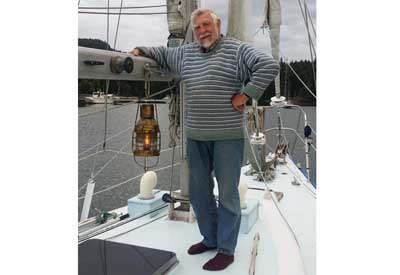

Setting the anchor light.

The Hecate was one of the Royal Navy vessels that also surveyed up and down the BC coast, and the settlers must have been English. Many a Hecate officer or cartographer lives on in Gulf Island place-names: Prevost, Bedwell, Browning. Spanish names come from explorers from 100 years earlier: Galiano, for example. The Coast Salish have taken back the name Penelekut, which is older still. Names are layered onto the beautiful Gulf Islands as unthinkingly as Christmas tags. They mostly have no relationship with the places they touch on a chart, save that hundreds of years earlier, someone bearing that name was there and saw the unchanging rocks and perhaps charted the beautiful coastline.

Catherine hangs the laundry on the stancheons at Genoa Bay.

Catherine hangs the laundry on the stancheons at Genoa Bay.

But back to the Hecate. Did the sailors and settlers poke their noses into Genoa Bay and decide against it because the settlers onboard were farmers and the tree-covered hills of Genoa Bay rear straight against the sky? Did they anticipate a difficult docking with a steep foreshore, and later a narrow trail that leads uphill and writhes like a grass snake in August? My morning walk in Cowichan Bay was refreshing; my morning walk in Genoa Bay was a gruelling ordeal that left me sweaty and gasping and potentially the hero of my fat-lady group.

“I’ve never SEEN such a road,” I complained to my husband. “Come with me?”

“No thank you,” John replied, who had lasted five minutes straight uphill the summer before he gave up and returned to drink $2.00 coffee from the bookstore at the pierhead and read an Inspector Banks mystery.

But Genoa Bay is protected. I wonder if the Hecate sailed into Genoa Bay first, though if it was on a day there was a south-easterly wind blowing straight at them they may have left as quickly as they could escape. There is nothing that pins you to the rocks faster in Genoa Bay than a south-easter and a slipping anchor.

One of the first Europeans to settle at Genoa Bay in the 1860s was a storekeeper who named the bay after his beautiful birthplace in Italy. The Genoa in Italy was an important trading centre and port for hundreds of years, and in a self-depreciating Canadian sort of way, Giovanni Baptiste Ordano did the same thing, establishing trading posts at Tzouhalem, Cowichan Bay, and San Juan Island in the US. Other opportunists saw the potential for lumber and a large sawmill operated in the bay from the 1870s until 1925. No doubt many of the sawmill workers were customers of Ordano the Italian mogul.

The sawmill used large saws, which periodically needed sharpening. Filings from 55 years of sawblade sharpening coalesced into two big rock-like formations that sit on the foreshore. Somebody had stuck a decorative heron on the top of the bigger heap.

“And that,” John told me, “is all that’s left of the sawmill.”

I stood and looked at the two filing heaps. There was a kind of bravery to them. Accommodations to tourists had sprung up all around them: An upmarket restaurant, a marina, a bookstore, a souvenir shop, and yet still the slag heaps sat. The trees had all grown back, the road toward Duncan was still tortuous, the hills were still imposing and daunting, and Genoa Bay was still best accessed by sea, even though the captain of the Hecate had preferred the better holding across the narrow water. And one man, a clever and ambitious entrepreneur, had walked across a continent to California, made his way north to rainy BC, and allowed himself one longing look back to the sunny city he’d left behind him, a place he’d never see again.

Genoa Bay.

The people who came before me, the layers of lives that were here first, are forever lost. They also cooked food and did chores. They worked and hoped and longed and remembered. And the houses here have amenities that would have been unimagined 150 years ago. But strip away what’s new – the docks, the road, the curious tourists in powerboats – and the essentials of tree and rock and water are still here. Along with two piles of iron filings and a name.