Ask Andrew: Suck Squeeze Bang Blow – The case for compression

Dec 8, 2022

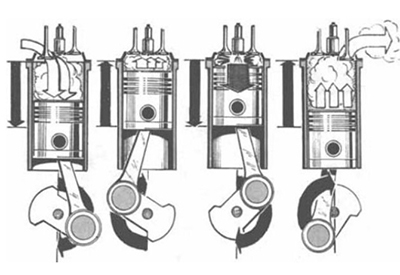

the 4 cycles of an engine: intake compression, power, exhaust

Pt 1: Compression in a gas engine

The massive block of iron sitting in your boat (or mounted atop your outboard) takes a lot of pressure (and not just metaphorically). Inside the engine block is where the magic happens: A crankshaft turns to perform work: turning a prop shaft and propeller to make the boat go.

This action is dependent on the up/down movement of the pistons, contained in cylinders inside the engine block. At the top of each cylinder is a pair of valves: The intake valve allows air into the cylinder. The exhaust valve lets air out.

The fitting of the piston in the cylinder is helped by piston rings: these rings allow a tight fit, but also provide a replaceable wear point. The movement of the tight-fitting piston is helped along with via oil lubrication.

A single piston moves up and down in a single combustion cycle. A 4-stroke engine will move have the piston move four times in a cycle: Intake, Compression, Power, and Exhaust (Suck squeeze bang blow)

The piston moves down, and as it moves, the intake valve allows air into the cylinder. The downward movement draws air into the cylinder, and when it reaches the bottom of it’s stroke, the intake valve closes.

The piston then begins to rise, with the valves closed, keeping air trapped inside and compressing it. As the air is compressed, it heats up. At the top of its stroke, atomized gas is added to the compressed air, and at just the right moment the spark plug ignites.

The resulting explosion forces the piston downwards, causing the crankshaft to turn and resulting in work being performed.

Inside the cylinder, gases from the explosion are vented as the piston rises on it’s fourth stroke and the exhaust valve opens to release it.

This process happens over and over again, in multiple cylinders for as long as the engine is running.

The engine needs three components to run – and if any of those components is missing, the engine either won’t start, or wont continue to run:

1) Fuel – the explosion has to happen for work to be performed. Without fuel available to burn, the work won’t take place

2) Spark – something to ignite that fuel. The spark plugs have to create sufficient spark to ignite the fuel to make it burn

3) The cylinders have to have a tight seal, and be compressed well to run and burn efficiently

Each of these three components that may be common causes of failure. Many of us have heard the term compression, but may not know what it means or how to measure or fix it.

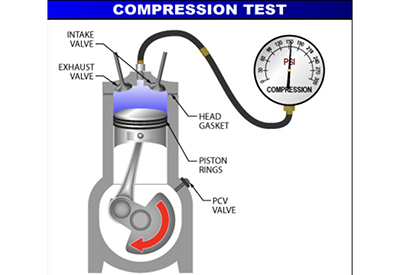

how compression is checked within an individual cylinder

how compression is checked within an individual cylinder

The cylinder’s compression is dependent on a few factors (not in any particular order)

a) The piston fits tightly in the cylinder. Worn piston rings can allow air to escape, preventing the pistons ability for it to be compressed

b) The piston is lubricated well. The wrong viscosity of oil can prevent movement of the cylinder, or might not fill the gaps between the cylinder wall and piston

c) Gaps at the top of the cyinder. A ‘cylinder head’ rests atop all of the cylinders in a row (one head may cover 1 or 2 or 4 cylinders, depending on the engine configuration). Engines are made of cast metal, and when two components are bolted together, a gasket is fitted between the two parts. Over time, with repeated compression and worn parts, the head gasket can become damaged, resulting in a ‘blown’ head gasket

d) The valves are damaged: a valve stem breaks or bends, or the valve edges become coated in carbon, resulting in a poor seal. Air escapes and compression is lost

e) The piston itself is damaged. All the explosions inside a cylinder can cause all sorts of problems over time

Diagnostically – It can be tough to isolate exactly why compression is low – but we can use a simple tool to determine what the compression is in each cylinder and therefore determine what to check next.

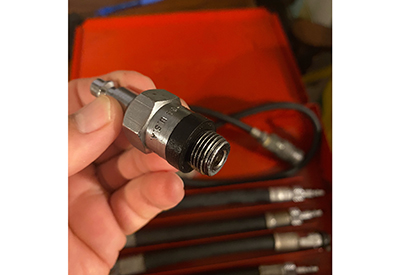

Compression tester and test steps

a standard compression test-kit for gasoline engines, with a number of adaptors that match the most common spark-plug thread types

a standard compression test-kit for gasoline engines, with a number of adaptors that match the most common spark-plug thread types

The compression tester has a threaded fitting that threads in at the top of each cylinder in place of the spark plug. As the engine is turned over, the crankshaft turns, the pistons move up and down, and the air in each cylinder is compressed (without starting the engine). The level of compression (the PSI) is read via a gauge attached to the threaded fitting.

Steps.

1) Disable the engine so that it doesn’t start accidentally (if youre unsure how to do this, consult with a qualified marine tech).

2) Mark the numbers and location of each cylinder.

3) Remove and label each of the spark plug leads. Ensure that these are appropriately grounded during the test

4) One at a time, remove a spark plug from the cylinder to be tested. Thread the fitting into the spark plug hole, and connect the gauge in each cylinder to test.

5) Once set up, apply power to the starter motor, or rotate the engine by hand (via a pull-cord or crank handle. Allow the engine to turn multiple cycles (5-10 seconds). Read and record the results for each cylinder. Ideal cylinder compression should be between 110 and 150 psi

the threaded end of a spark-plug adaptor

the threaded end of a spark-plug adaptor

The results:

If multiple cylinders, side-by-side have low compression, the head gasket may be blown in a location between the two.

If only one cylinder has low compression, with the others reading high, the problem is isolated – meaning that the cylinder walls, piston, rings, and valves in that single cylinder should be checked. The cylinders should read within about 10psi of each other.

If all cylinders are reading low compression, this would point to age and even wear: valves, gaskets, and piston rings, as well as a check on the quality of oil used.

If a cylinder has high compression, there may be debris, water or build-up inside the cylinder which is creating a condition where the tester registers a higher-than-normal condition.

Special note: As always, it’s important to be aware of safety measures and appropriate steps and tools to take in any sort of DIY project. If you’re unsure at any step in the process, be sure to consult a qualified marine tech for advice or assistance prior to performing a compression test.

Next time – diesels.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.

Andrew McDonald is the owner of Lakeside Marine Services – a boat repair/maintenance firm based in Toronto. Andrew has worked in the marine industry for 12 years and is a graduate of the Georgian College ‘Mechanical Techniques – Marine Engine Mechanic’ program.